Viewpoint: Science cuts 'could lead to brain drain'

- Published

.jpg)

Hundreds of planets orbiting other suns have been detected in the past several years

In a Viewpoint article, Paul Crowther, professor of astrophysics at the University of Sheffield, warns that cuts in the UK's science budget could be devastating and lead to a massive "brain drain" of young British graduates.

Wednesday 20 October, is making Joanne Bibby nervous.

Her anxiety is understandable since it's the date she defends her thesis at the University of Sheffield. The exam represents the final hurdle before she qualifies as a research astronomer, and heads off to a post-doctoral position in Manhattan at the American Museum of Natural History.

Wednesday 20 October is also making me nervous. In part, this is because I have supervised her work over the past three years.

Mostly though, it's because the UK scientific community is likely to discover the depth of cuts to the science budget in the comprehensive spending review that date.

Lord Browne's widely publicised review of the funding of university teaching will have far-reaching consequences both for students and universities.

Far fewer column inches have been devoted to upcoming cuts to the civil science budget.

Yet the squeeze on science - administered through seven Research Councils and representing a little over 0.5% of public spending - may be equally significant in the long-term.

'More with less'

Joanne's move across the Atlantic is typical of the historical ebb and flow of scientists between the UK and elsewhere. From a low base in the 1980s, the UK has undergone a "brain gain" over the past decade or so, as investment in science has kept pace with economic growth.

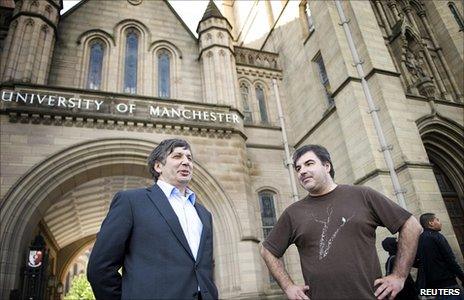

The award of the Nobel Prize for Physics this month to Russian-born, though Manchester-based, scientists for their discovery of the "wonder material" graphene reflects the high current international standing of UK science.

Paul Crowther says the UK could "lose access to telescopes scanning the night sky"

However, warnings about the need to do "more with less" have led to fears that the past decade's investment will be undone through a "brain drain".

Concerns have led to protests against the proposed cuts via the Science is Vital, initiated by cell biologist Jenny Rohn. A petition against science budget cuts accumulated 34,000 signatures within a fortnight, many from beyond academia, and was handed into Downing Street last week.

Science has a relatively low profile with respect to basic public services, but is a great success story for the UK.

Even the Prime Minister highlighted the need to invest in our science and technology base in the final leadership debate, to wean our economy off the service sector and banking.

Damage to economy

Other countries in difficult financial positions are maintaining their science base, or even increasing investment. Former science minister Lord Waldegrave has warned that short-term cuts to science, technology and innovation may damage our economic growth in the long-term.

The Royal Society has weighed into the debate by suggesting that a large real-term cut to science budgets could mean "game over".

Should such warnings be treated seriously? Based on the recent experience of my own scientific community the answer is a clear yes. Research into understanding the Universe on both very small and very large scales has already been stung by cuts over the past three years, at a time when the wider economy was still booming.

Most of the budget of the STFC (Science and Technology Facilities Council) - the Research Council responsible for supporting fundamental physics in the UK - is tied up in staff, operating costs for laboratories, and subscriptions to access cutting-edge international facilities.

Consequently, a relatively small reduction in funding has had a disproportionate effect.

In astronomy, the volume of university research grants has almost halved within just three years, hitting the next generation of scientists hardest.

'Golden age'

For the first time ever we are on course to lose access to telescopes scanning the night sky from directly above our heads.

It is depressing that the funds available to UK astronomical research now looks set to diminish further, particularly given that all but the highest priority programmes have already been curtailed.

Manchester-based winners of Nobel Prize in physics were born in Russia

In contrast, the public appetite for astronomy, cosmology and space science is on the increase.

We are living through a "golden age" of discovery. Hundreds of planets orbiting other suns have been detected, most of the matter in the Universe is "dark", while geysers have been witnessed on one of Saturn's moons, the latter featured in Brian Cox's Wonders of the Solar System series which attracted millions of viewers earlier this year.

If the STFC were to receive a further major cut, various unpalatable options would arise.

Either it could mothball laboratories used by scientists from other disciplines, withdraw support for students and research staff such as Joanne, or even withdraw from one of the "big science" international clubs, such as Cern or ESO.

Politically, the latter might appear the least bad option, but withdrawal would relegate the UK from the Premier league to Sunday league in either particle physics or astronomy.

Besides, huge penalty clauses wouldn't save any money in the short-term, and merely signal that the UK is no longer a credible international partner.

We are genuinely world-beating in these subjects, yet the STFC might be forced to retreat entirely from one of these fields, despite astronomy, cosmology and particle physics being responsible for attracting students to physics at university.

More generally, severe science budget cuts would signal that the UK is less attractive for private investment than other countries, reducing our competitiveness.

Businesses would be less likely to fill the gaps in public support for research, leading to a narrowing of our broad research base.

Some disciplines are relatively insulated from cuts through support from charities, whereas others have little alternative sources of funding, especially those in the physical sciences.

Curiosity-driven research in physics and chemistry may not have obvious economic benefits, yet major advances can come from the most unexpected of places: graphene was discovered using nothing more sophisticated than sticky tape; document handling at Cern led to the establishment of the world-wide web; and GPS technology in mobile phones arose from radio astronomers' attempts to measure the size of distant quasars.

UK industry desperately needs more scientists and engineers, but without a positive signal from the government, many young people will either choose a different career or the trickle of scientific talent overseas will become a flood.

Joanne, and many of her contemporaries, having been trained through the public purse, might leave for good.

Scientists do live in the real world, and worry about public sector cuts as much as everyone else.

Still, let's hope that HM Treasury recognizes that long-term economic recovery will be enhanced through stable investment in science, technology and engineering.

Paul Crowther is a professor of astrophysics at the University of Sheffield, UK

- Published20 October 2010

- Published19 October 2010

- Published18 October 2010

- Published13 October 2010

- Published23 September 2010