Charles Duke recalls driving on the Moon

- Published

Charlie Duke: 'We crashed on the Moon 1,000 times'

Many motorists retain fond memories of cars they have owned or driven.

For Charles Duke, riding Nasa's lunar rover remains one of his most vivid recollections of the Apollo 16 mission to the Moon in 1972.

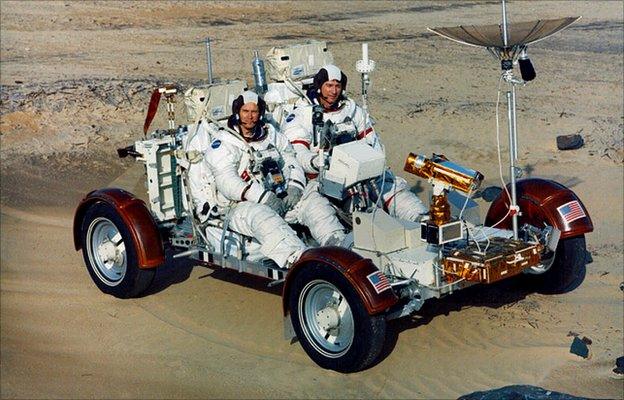

In April that year, Duke and fellow astronaut John Young drove the go-cart-like vehicle across the rough terrain of the Moon's Cayley Plains.

They were surveying the local geology and collecting rock and soil samples for return to Earth.

"We drove down and drove up the side of what we call Stone Mountain which is about 300ft above the valley floor," he tells me.

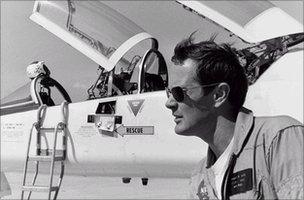

Duke describes training for the missions as "arduous"

"We'd turned around and there was this magnificent sight as I looked across this grey valley - all the way to the far side," he recalls.

"And there was this little lunar module out there in the lunar valley. It was very, very vivid."

When the BBC meets Mr Duke, he is at Coventry's Ricoh Arena to give the keynote speech to the conference of the Institute of Sales and Marketing Management, external.

In tough economic times, it seems, people could use some extra inspiration.

The 75-year-old is having lunch when we make contact with his representative, which gives us some time to set up our room for the interview.

When he walks into the room, the southern accent is unmistakeable. Dressed in a smart grey suit and a red tie emblazoned with planes, he is affable, articulate and humble.

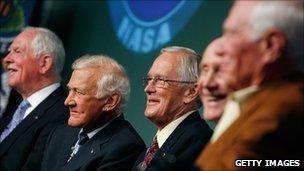

Charles, or Charlie, Duke, external is one of 12 people who have walked on the surface of the Moon. Nine of those men are alive today; Duke is the youngest of them.

Like many Apollo-era astronauts, he is a former test pilot: "Two months after I got out of test pilot school, I saw an advert that said Nasa was recruiting more astronauts. The best job you could have as a test pilot was being an astronaut, so I volunteered."

Duke (L) spent hours training with John Young in an Earthbound replica of the lunar rover

Inducted into Nasa's astronaut class of 1966, Duke describes the training he went through as "arduous".

He was the voice of mission control during the first Moon landing three years later, an unbearably tense affair in which astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin approached the ground in a spindly lunar module which some people doubted could land safely at all.

"In the final moments, we were running out of fuel," Mr Duke explains.

"Due to the fact that our guidance had not been correct, we had targeted him (lunar module pilot Armstrong) into a big field of boulders. So he had to overfly that, which took an extensive amount of fuel."

Rarely, he recalls, mission control was shrouded in silence until Buzz Aldrin's voice came in over the comms: "Contact, engine stop."

"We knew they were on the Moon. A few moments later, Neil Armstrong said: 'Houston, Tranquility Base, here. The Eagle has Landed," says Duke.

Charlie Duke on Apollo 11: 'I thought we'd have to abort'

"I was so excited I couldn't even pronounce Tranquility. It came out 'Twang' at first. Then I corrected myself and said: 'Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground, you've got a bunch of guys about to turn blue, we're breathing again'."

"I really meant it, I was holding my breath the last minute or so."

Duke waited three years and four flights for the chance to follow in the wake of Neil Armstrong's nerve-jangling lunar touchdown in 1969.

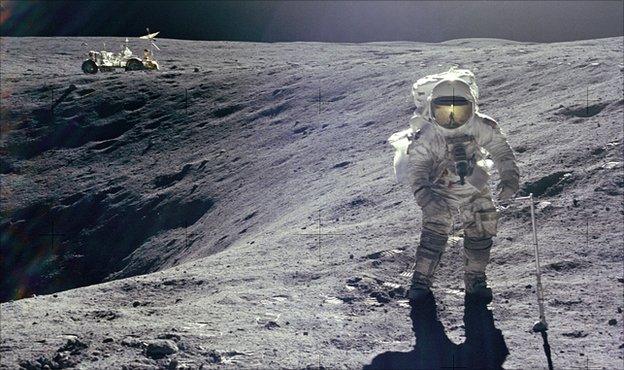

He safely piloted the Apollo 16 lunar module, known as Orion, to a site on the Moon's Descartes region. And although the bumpy lunar drives stick in his mind, the landing remains his predominant recollection of the mission.

"We were going in a spot where the best resolution we had of the surface was 45ft," he explains.

"There are a lot of big holes that are less than 45ft. We had to manoeuvre round all this stuff that we'd just seen for the first time. So the landing from a pilot's perspective was very dynamic."

Duke and Young made three forays on to the lunar surface, spending nearly 72 hours on the Moon

At the time, the Apollo 16 astronauts set the record for the longest stay on the Moon, external, spending nearly 72 hours on the surface (this was surpassed on the next Apollo landing). During the mission, Duke left a very personal memento on the Moon for posterity - a family photo depicting Charles, his wife Dottie and their two young sons.

Nearly 40 years on from his lunar sojourn, the 75-year-old is clear on what he would do if given the opportunity to return: "If I had the chance to return to the Moon, and we got to land on the Cayley Plains as we did, I would like to see what the status of our lunar rover, external was - I think it would be in good shape - take a new battery, change it out and drive it off!"

Charles Duke now lives with Dottie, his wife of more than 40 years, in a town outside San Antonio, Texas. He is a Christian lay witness and runs the Duke Ministry for Christ organisation.

Duke (c) joined other Apollo astronauts in 2009 to mark the 40th anniversary of the first Moon landing

It is oft-repeated that several of the Apollo astronauts "found God" after their experiences on the Moon. Mr Duke had grown up with Christianity, but his wife Dottie has credited a renewed focus on religion for healing their marriage after the couple went through problems.

Many of the Apollo veterans hold strong views about the current course of human spaceflight in the US. With the shuttle fleet being retired, the US could be reliant on Russia for carrying its crews into space for many years to come.

Constellation - the plan outlined by President George W Bush that would have returned astronauts to the Moon by 2020 - was cancelled in the review of manned spaceflight commissioned by President Obama.

"I believe [the cancellation] was a disaster," Mr Duke says.

US Congress now appears set on a compromise, with the job of re-supplying the space station handed over to commercial outfits and Nasa tasked with developing a spacecraft for deep space exploration.

Duke left a family photo on the Moon for posterity

"Buzz Aldrin doesn't think we need to go back to the Moon - that we should go straight on to Mars. I'm more on the side that says we should go back to the Moon. I think there's a lot we can utilise the Moon for scientifically," Mr Duke explains.

"We could establish a base similar to ones in Antarctica where we could live for months at a time."

But if and when humans return to the Moon, should those original Moon landing sites be protected because of their historic interest?

"There is nothing to disturb them right now except a meteorite strike nearby. I don't think rogue explorers coming to desecrate them is going to be a problem.

"I think the future of lunar bases has to be somewhere around the South or North Pole. You have less variation in temperature and more daylight hours.

He adds: "I don't think it's important scientifically, but out of curiosity it would be nice to go back to one of the Apollo sites and see what it looked like."