Mars 'hopper' may run on nuclear decay and Martian CO2

- Published

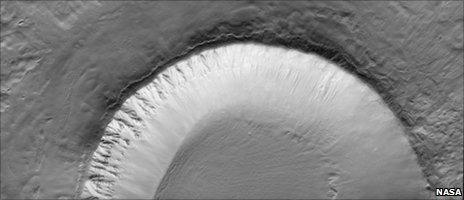

The Nasa landers did plenty of science but did not see much of the planet

Nuclear decay-driven machines could gather gases from the atmosphere of Mars, giving future robotic missions leaps of a kilometre, researchers say.

A design concept in Proceedings of the Royal Society A, external outlines an approach to compress CO2 and liquefy it.

The liquid would then be heated much as in a standard rocket, expanding violently into a gas to propel exploratory craft great distances.

The authors suggest this is a better strategy to see more of the Red Planet.

While the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity have been outstanding science successes, providing far more data than was initially planned, as vehicles that are powered by the sun and get around on wheels they are limited in their overall range of exploration.

For example, the Opportunity rover, which has been on the Martian surface for nearly seven years, passed the 25-kilometre mark this week.

As a result, researchers have been looking into means of getting farther with future robotic missions to Mars. Ideas including landers with wings or lighter-than-atmosphere balloons have been proposed, or even "inflatable tumbleweeds" that are blown across the landscape.

However, Hugo Williams and his colleagues Richard Ambrosi and Nigel Bannister at the University of Leicester - working on the propulsion ideas for a lander project that includes the aerospace giant Astrium - argue that a lander that can gather up its own propellant is best, external.

In the proposed hopper design, heat from the decay is gathered and used to run a compressor, collecting the CO2-rich Martian atmosphere into a tank and compressing it until it turns into a liquid.

At the heart of the idea is a radioisotope-based generator - a few-kilogram piece of radioactive material that heats up as it regularly spits out tiny subatomic particles.

"Nuclear batteries" employing the same principle have been in use in long-term space missions since the Pioneer craft of the early 1970s.

Some of the heat is channelled to another block of material that is used as a storage heater. When a boost is needed the liquid is allowed to contact the block, quickly turning back into a gas and heating up.

When passed through a standard rocket nozzle, the expanding CO2 gas provides thrust that can launch a lander and provide a soft landing when it "hops" to its new locale.

Propulsion on the basis of compressed CO2 is not a new idea; programmes by firms including Pioneer Astronautics have carried out some development work on the concept.

But Dr Williams and his co-authors brought together the radioisotope generator and CO2 propulsion ideas and can now begin to come to firm conclusions about how a system would perform on Mars.

"The advantage is that the radioisotope source is long-lived and not dependent on solar energy," Dr Williams explained to BBC News.

"You can operate for a long time, and in areas of Mars where the amount of sunlight is relatively small. Because you're collecting your propellant from the Martian atmosphere you're not limited by having to take propellant out from Earth."

The concept design would require a week to gather sufficient propellant for a hop of about a kilometre, but eventual designs will accommodate the needs of exploratory missions, pausing less or more time at each landing site.

Manuel Martinez-Sanchez, director of the Space Propulsion Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said the idea seemed sound but raised one concern about its potential robustness.

"Radioisotope generators are intrinsically dangerous... and they contain materials -not only radioactive, but highly poisonous - that should never be released to the environment," he explained to BBC News.

"It does not seem wise to place one of these things on a 'bouncer', subject to periodic impact loads on unpredictable terrain."

The team admits the idea is very much in the formative stages, and is in the process of refining it.

- Published24 May 2010

- Published6 September 2010