Goce gravity mission traces ocean circulation

- Published

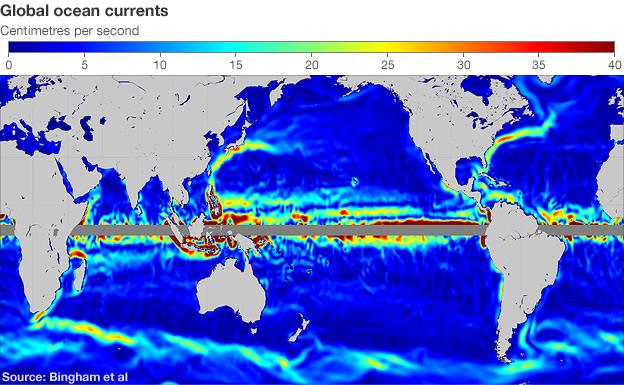

The ocean currents disperse heat, nutrients and even pollutants around the globe

The great sweep of water around Planet Earth has been captured from space in greater detail than ever before.

New observations from Europe's Goce gravity mapping satellite have allowed scientists to plot ocean currents with unprecedented precision.

Understanding gravity is fundamental to being able to track the direction and speed of water across the globe.

The data should improve the climate models which need to represent better how oceans move heat around the planet.

Very strongly represented in the new map is the famous Gulf Stream, the most intense of all the currents where water zips along at velocities greater than one metre per second in places.

"The Gulf Stream takes warm water from the tropics and transports it to higher latitudes, and that warmth is released to the atmosphere and keeps the British Isles, for instance, much warmer than they would otherwise be," said Dr Rory Bingham from Newcastle University, UK.

"When this water has reached higher latitudes, still, because it is by then cold, salty and dense, it will sink; and you get this overturning circulation that helps regulate Earth's climate," he told BBC News.

Dr Bingham presented his ocean circulation data, external using the latest information from Goce at the recent American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, the largest annual gathering of Earth and planetary scientists.

Goce flies lower than any other scientific satellite

The European Space Agency (Esa) satellite was launched in March 2009, and is delivering a step change in our vision of how gravity varies across the globe.

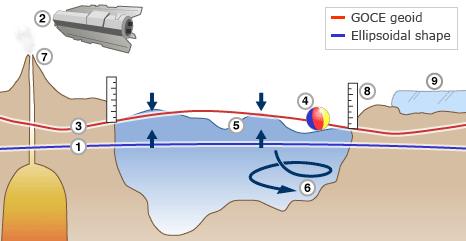

Contrary to popular perception, the pull of gravity is not the same everywhere. There are actually very subtle differences in the tug exerted by the mass of the planet from one place to the next.

In the oceans, this has the effect of making water bulge over great submarine mountain ranges and to dip over the deepest ocean trenches.

Goce, which circles the Earth from pole to pole, carries a state of the art gradiometer to sense the variations on a scale better than 100km.

The information is critical to oceanographers attempting to trace the currents.

Without the Gulf Stream, the UK would routinely experience much colder winters than it does

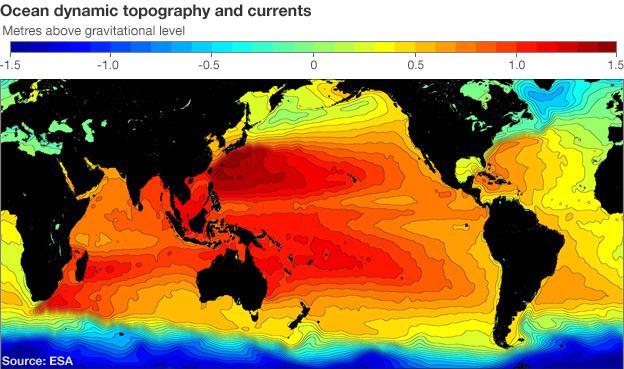

If they compare the gravity information with measurements of sea surface height made by other spacecraft, they can establish a much better picture of where water is piled up and where it is likely to flow and at what speed.

Very accurate data on currents is already obtained from drifting sensors thrown into the water, but these are necessarily just point measurements.

Oceanographers would hope therefore to combine the truly global perspective they can only get from Goce and other satellites with the "ground truth" they can retrieve from drifters.

Add in further data collected about sea temperature and it becomes possible to calculate the amount of energy the oceans are moving around Earth's climate system.

Computer models that try to forecast future climate behaviour have to incorporate these details if they are to improve their simulation performance.

Data on sea-surface height combined with gravity information tells scientists where the water is piled up

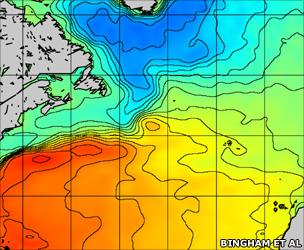

"The new information coming from Goce is amazing," said Dr Bingham. "We're getting down to very fine scales now. It's incredible to think for example that we can sense from space very small circulation features like the Mann Eddy, a persistent pocket of water in the Atlantic that just goes around and around."

The ocean circulation information presented at AGU was built using just two months of Goce gravity data.

Scientists expect to construct improved maps when they understand better how the satellite's sophisticated instrument behaves and the observations accumulate.

The Mann Eddy (image centre) is a persistent clockwise circulation in the middle of the Atlantic

Goce is not expected to be a long-lived mission. Flying at an altitude of just 255km - the lowest orbit of any research satellite in operation today - it experiences significant drag from the atmosphere.

This has to be counteracted by constantly throttling an ion thruster on the back of the satellite.

When the fuel for the thruster runs out, however, Goce will fall from the sky.

"We have the funding and resources on board to go until at least the end of 2012," said Dr Rune Floberghagen, Esa's Goce mission manager. If European governments then provide additional money and Goce can be frugal with its fuel reserves, the end date could move out to 2014.

Goce is an acronym for Gravity field and steady-state Ocean Circulation Explorer.

It is part of a series of missions that aim to do innovative science in obtaining data on issues of pressing environmental concern.

Goce probes gravity field variations

Earth is a slightly flattened sphere - it is ellipsoidal in shape

Goce senses tiny variations in the pull of gravity over Earth

The data is used to construct an idealised surface, or geoid

It traces gravity of equal 'potential'; balls won't roll on its 'slopes'

It is the shape the oceans would take without winds and currents

So, comparing sea level and geoid data reveals ocean behaviour

Gravity changes can betray magma movements under volcanoes

A precise geoid underpins a universal height system for the world

Gravity data can also reveal how much mass is lost by ice sheets

- Published7 September 2010