City street to open sea - fish farming's new frontiers

- Published

The fish farms of the future could reside in city skyscrapers... or the open ocean

Already, almost half of the fish we eat comes from farms rather than the wild ocean.

And with the human population set to expand by about two billion people between now and the middle of the century, and with yields from fishing flat-lining as stocks decline, that proportion is set to increase dramatically.

But given the environmental issues that have dogged fish farming down the years - pollution, disease, the need for wild fish to feed to the farmed ones - how can the industry expand so far without creating major problems?

And where are all the extra fish farms to go?

On all fronts, aquaculture is searching for new frontiers.

And the indications are that the industry of the future will farm different species, use novel integrated production methods, and explore new physical environments, from city centres to the open ocean.

"The forecast is that by the year 2050 there will be a shortage of land for food production," says Patrick Sorgeloos from Ghent University in Belgium, an aquaculture adviser to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

"And on top of that, freshwater will be a really precious resource that we will not be able to waste or use to expand freshwater aquaculture.

"So the FAO and other organisations are very much convinced that the future for aquaculture is much more in the marine environment - and with 70% of the globe covered by sea, we have a great opportunity to get more food produced there."

Already, the bays and inlets of many coastlines are chock full of fish pens and floating platforms for shellfish.

Some companies have responded by moving to more far-flung locations - to uninhabited peninsulas or islands.

"In Canada already they're in remote locations, with staff living on barges, and the same thing's happening in Chile," says Steve Bracken, business support manager for Marine Harvest.

This company - the world's biggest producer of farmed salmon - is now looking at starting similar remote operations off the west coast of Scotland.

"The waters would be faster flowing, deeper, and ideal locations for farming salmon," he says.

"But that brings a degree of remoteness - it's likely we'd have staff living and working there, so they'd be some kind of residential fish farms."

Marine Harvest has outlined plans for barge-based operations, each of which would entail a staff of six living and working on the farm, much as oil-rig workers or lighthouse-keepers do today.

But things could go further.

"One idea that's been put forward is that smolts - which are the start of the grow-out period for salmon in the sea, as young fish of 60-80g - could be put on board a large vessel, and then the vessel heads up the west coast of America to California," says Steve Bracken.

"By the time it gets there, the fish are at market size. It would be a slow journey - but it's an exciting prospect."

Blue horizons

Another avenue for expansion is through looking at species that are not currently staples, but that are palatable and ideal for farming.

Bluefin tuna, for example, are under huge pressure in the wild as the favoured species for sushi and sashimi.

Open ocean fish-farming opens a new chapter in mankind's dominion over the seas

Farming them from scratch would be a natural step; but it has proved really hard to do.

The Kona Blue company, operating in Hawaii, believes it has a solution; stop eating bluefin, and start eating Kona Kampachi.

"We can't just rely on pillage and plunder from wild stocks anymore - we have to produce it ourselves, and we have to produce it in the open ocean, in deeper water," argues the company's co-founder Neil Sims.

"What we have to do is to winnow through the marine species; and those that are the best targets for wild fisheries may not be the best species for us to farm long-term."

Derived from the Almaco Jack or kahala, the company says Kona Kampachi is not only a good replacement from the palate's perspective, but also because the fish can be farmed sustainably.

Key to that sustainability, it says, is that the farm is located in open ocean, half a mile off the coast of Kona island, with the strong currents able to remove the fish's faeces and any other pollutants.

Fresh to your door

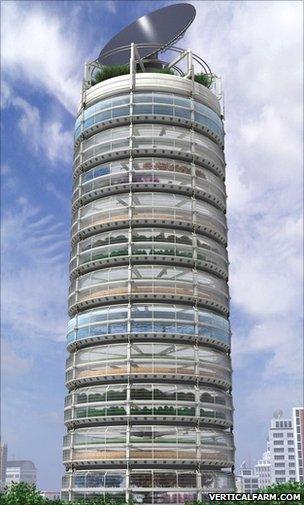

At the other end of the scale from open-sea cages and vast barges full of salmon smolts are urban fish farms - water in the heart of the city, close to where the eager consumer awaits.

"There's no limit except your imagination as to what we can do indoors," says Dickson Despommier, the Columbia University professor who developed the concept of vertical farming a decade ago.

"We can produce shrimp, we can produce molluscs; you can raise trout, striped bass, catfish..."

The vertical farming concept began with a challenge to Columbia University students to find new ways of feeding New York's teeming millions.

The answer was, special skyscrapers... and if they can produce plants, why not fish as well?

Space and resources, not least water, are at a premium - hence the development of techniques such as aquaponics, a variant of the water-frugal plant-growing technique of hydroponics.

"In aquaponics, what you do is place the growing bed of the vegetables or flowers or whatever you're growing in the flow of the water coming out of the fish tanks," explains Martin Schreibman from Brooklyn College in New York.

"It's the fish wastes, the breakdown products of protein metabolism, that provide the nitrates and phosphates for plants.

Aquaculturalists are diversifying into produce such as seaweed - often in conjunction with fish

"So I now have a system with styrofoam floats, there are holes in the styrofoam that contain the plants - we've got pak choi and lettuce at the moment - and the water is plumbed back into the fish tank, so you've got a closed cycle."

Several cities are investigating vertical farming - Portland, Los Angeles, Las Vegas inside the US, Beijing, Incheon, Abu Dhabi elsewhere.

One option would be to run the farms as community enterprises in which people could take a share - akin to allotments used for growing vegetables

Just as with the ocean-going salmon barges, there is a lot of work to be done before vertical fish farms become standard... but given rising food prices, the squeeze on land, the growing human population and the increasing taste for local food, perhaps its day is coming.

Fancy turbot for dinner, or some shrimp for tomorrow's salad? Just nip across to the aquaponics centre, pluck some out, and 10 minutes later they are in the pan.

Sounds appetising; but Dickson Despommier sees other reasons to pursue the dream.

"If vertical farming proves successful... then if you were to take a picture today of the skyline of New York or London or Shanghai and then compare that to 50 years later, you'd see a remarkable change," says Dickson Despommier.

"You'd see absolutely gorgeous, tall transparent buildings, apartment houses with three or four stories of transparent vertical farming on top... and you've taken food out of the hands of a few mass producers and placed it into the hands of all the people."

You can find out more about the possible futures of aquaculture in this week's edition of One Planet on the BBC World Service.

- Published27 September 2010