Ancient rock art's colours come from microbes

- Published

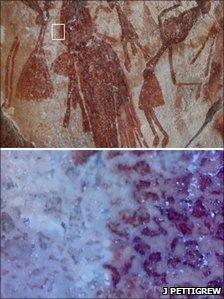

The indicated region (white box) shows black fungi at a sharp boundary

A particular type of ancient rock art in Western Australia maintains its vivid colours because it is alive, researchers have found.

While some rock art fades in hundreds of years, the "Bradshaw art" remains colourful after at least 40,000 years.

Jack Pettigrew of the University of Queensland in Australia has shown that the paintings have been colonised, external by colourful bacteria and fungi.

These "biofilms" may explain previous difficulties in dating such rock art.

Professor Pettigrew and his colleagues studied 80 of these Bradshaw rock artworks - named for the 19th-Century naturalist who first identified them - in 16 locations within Western Australia's Kimberley region.

They concentrated on two of the oldest known styles of Bradshaw art - Tassel and Sash - and found that a vast majority of them showed signs of life, but no paint.

The team dubbed the phenomenon "Living pigments".

"'Living pigments' is a metaphorical device to refer to the fact that the pigments of the original paint have been replaced by pigmented micro-organisms," Professor Pettigrew told BBC News.

"These organisms are alive and could have replenished themselves over endless millennia to explain the freshness of the paintings' appearance."

Among the most frequent inhabitants of the boundaries of the artwork was a black fungus, thought to be of the group of fungi known as Chaetothyriales.

Successive generations of these fungi grow by cannibalising their predecessors. That means that if the initial paint layer - from tens of thousands of years ago - had spores of the fungus within it, the current fungal inhabitants may be direct descendants.

Black fungi with yellow "fruiting bodies" (left), alongside red bacteria, give one work its colours

The team also noted that the original paint may have had nutrients in it that "kick-started" a mutual relationship between the black fungi and red bacteria that often appear together. The fungi can provide water to the bacteria, while the bacteria provide carbohydrates to the fungi.

The exact species involved in these colourations have yet to be identified, and Professor Pettigrew said that the harsh conditions in the Kimberley region may hamper future research.

However, even the suggestion of these "living pigments" may explain why attempts to date some rock art has shown inconsistent results: although the paintings may be ancient, the life that fills their outlines is quite recent.

"Dating individual Bradshaw art is crucial to any further understanding of its meaning and development," Professor Pettigrew said.

"That possibility is presently far away, but the biofilm offers a possible avenue using DNA sequence evolution. We have begun work on that but this will be a long project."

Didier Bouakaze-Khan, a rock art expert from University College London, said that "there's a general consensus that what we're looking at might not purely be pigment as it was applied when the depictions were made", but that studies like this one would help archaeologists worldwide to take into account what effects life itself may be having on the art.

"It's very interesting and very exciting what they're showing - that there's some microorganisms going into the pigments and not destroying them, which is usually what's associated with the effect," he told BBC News.

Speaking about African rock artists, he said that "they had an intimate knowledge of ingredients theye were using and knew how long they would last, the rate of decay and how dark they would go and so on - not necessarily them controlling it, but they were definitely aware."

As such, Dr Bouakaze-Khan said it would be interesting to investigate whether the Bradshaw artists knew about the long-term effects of the specific pigments they used in their works.