Ancient humans, dubbed 'Denisovans', interbred with us

- Published

Professor Chris Stringer: "It's nothing short of sensational - we didn't know know how ancient people in China related to these other humans"

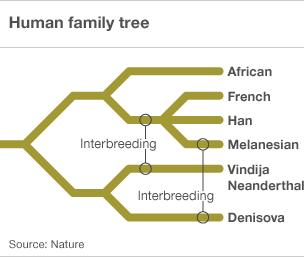

Scientists say an entirely separate type of human identified from bones in Siberia co-existed and interbred with our own species.

The ancient humans have been dubbed Denisovans after the caves in Siberia where their remains were found.

There is also evidence that this group was widespread in Eurasia.

A study in Nature journal shows that Denisovans co-existed with Neanderthals and interbred with our species - perhaps around 50,000 years ago.

An international group of researchers sequenced a complete genome from one of the ancient hominins (human-like creatures), based on nuclear DNA extracted from a finger bone.

'Sensational' find

According to the researchers, this provides confirmation there were at least four distinct types of human in existence when anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) first left their African homeland.

DNA from a tooth (pictured) and a finger bone show the Denisovans were a distinct group

Along with modern humans, scientists knew about the Neanderthals and a dwarf human species found on the Indonesian island of Flores nicknamed The Hobbit. To this list, experts must now add the Denisovans.

The implications of the finding have been described by Professor Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London as "nothing short of sensational".

Scientists were able to analyse DNA from a tooth and from a finger bone excavated in the Denisova cave in southern Siberia. The individuals belonged to a genetically distinct group of humans that were distantly related to Neanderthals but even more distantly related to us.

The finding adds weight to the theory that a different kind of human could have existed in Eurasia at the same time as our species.

Researchers have had enigmatic fossil evidence to support this view but now they have some firm evidence from the genetic study carried out by Professor Svante Paabo of the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, Germany.

"A species of early human living in Europe evolved," according to Professor Paabo.

"There was a western form that was the Neanderthal and an eastern form, the Denisovans."

The study shows that Denisovans interbred with the ancestors of the present day people of the Melanesian region north and north-east of Australia. Melanesian DNA comprises between 4% and 6% Denisovan DNA.

David Reich from the Harvard Medical School, who worked with Svante Paabo on the study, says that the fact that Denisovan genes ended up so far south suggests they were widespread across Eurasia: "These populations must have been spread across thousands and thousands of miles," he told BBC News.

One mystery is why the Denisovan genes are unique in modern Melanesians and are not found in other Eurasian groups that have so far been sampled.

'Fleeting encounter'

Professor Stringer believes it is because there may have been only a fleeting encounter as modern humans migrated through South-East Asia and then on to Melanesia.

The remains were excavated at a cave site in southern Siberia

"It could be just 50 Denisovans interbreeding with a thousand modern humans. That would be enough to produce this 5% of those archaic genes being transferred," he said.

"So the impact is there but the number of interbreeding events might have been quite small and quite rare."

No one knows when or how these humans disappeared but, according to Professor Paabo, it is very likely something to do with modern people because all the "archaic" humans, like Denisovans and Neanderthals disappeared sometime after Homo sapiens sapiens appeared on the scene.

"It is fascinating to see direct evidence that these archaic species did exist (alongside us) and it's only for the last few tens of thousands of years that is unique in our history that we are alone on this planet and we have no close relatives with us anymore," he said.

The study follows a paper published earlier this year by Professor Paabo and colleagues that showed there was interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals as they emerged from Africa 60,000 years ago.

- Published21 December 2010