Ammonite diet revealed in X-rays

- Published

In amongst the tongue-like radula, the X-ray images found the traces of a final meal

Ask someone to name their favourite fossils and the chances are they will point to the ammonites.

These coiled remains of ancient squid-like creatures are in every child's rock collection.

The animals were a big success, filling the oceans for 350 million years before going extinct with the dinosaurs.

Now, exquisite X-ray images featured in Science magazine, external are providing new insights on how the ammonites lived and perhaps also on why they died out.

The pictures have been produced by a team of French and American researchers using the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, external (ESRF) in Grenoble.

They reveal the mouthparts of three ammonite specimens discovered in Belle Fourche, South Dakota, US, a place renowned for the excellent preservation of fossils.

The fossils are actually from a grouping of straight, or uncoiled, ammonites known as Baculites, external but the implications should hold across a great swathe of species.

Beautiful 3D reconstructions lay bare the physical characteristics of the molluscs' jaws and a tongue-like structure called the radula.

The imagery is important because of what it says about the feeding habits of these prehistoric marine invertebrates.

Although "ten a penny" in terms of their abundance, the fossils still hide some secrets about the living animals' ecology.

"Ammonites are iconic fossils; everyone knows them, but actually we have very few data on the animals themselves," explained Isabelle Kruta from the National Museum of Natural History, Paris. "We have their shells but beyond that it's all been speculation."

With no direct counterpart today, it has been difficult to nail down the ammonites' true place in the ancient food chain.

But the analysis by Kruta and her colleagues indicates their ammonites would have dined on small organisms floating in the water, such as zooplankton, tiny crustaceans, and even other petite ammonites.

In one of the specimen's mouths the team found the remains of what was probably the animal's last meal, diced up by the jaws and the teeth-laden radula.

If plankton provided the major part of the ammonite diet then this could help explain their extinction 65 million years ago, the team believes.

The asteroid or comet impact widely implicated in the dinosaurs' demise would also have damaged plankton production in the oceans.

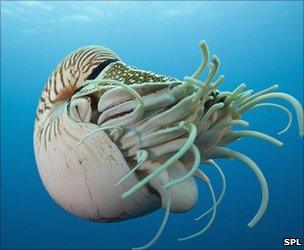

The modern nautilus looks similar but it has far more robust feeding equipment

Depleted food resources could have been a decisive factor therefore in pushing the ammonites over the edge.

"Pretty much all the community thought they were carnivorous but we didn't know exactly what they were eating," said Ms Kruta.

"People have pictured them catching fish or eating clams. But we've found they couldn't eat large, hard prey; they were not able to tear apart pieces of flesh," she told BBC News.

Ammonites were cephalopods; their nearest living relatives are animals like squid, octopus and cuttlefish.

And although the modern nautilus looks superficially like an ammonite, it is in fact a more distant cousin. Indeed, the nautilus has far more robust mouth parts; and can scavenge a wide variety of food sources. This fact may in part explain why the ancestors of the modern nautilus survived the space impact and the ammonites did not, say the researchers.

Computer reconstruction of the ammonite mouthparts, explained by Isabelle Kruta

From their first appearance in the Early Devonian Period (about 400 million years ago), ammonites underwent an explosive diversification.

Today, many thousands of species are known from the fossil record.

This great wealth of different forms through Earth history means they can be used as a dating tool by geologists - if a rock contains a particular fossil ammonite then that rock must be of a certain age.

The ESRF has pioneered the X-ray study of such palaeontological specimens.

The machine produces an intense, high-energy light that can pierce just about any material, revealing its inner structure.

Its advantage is that the investigation is non-destructive - it provides information that could otherwise only be obtained by cutting into a fossil.

The X-ray microtomography data also captures very fine details which can then be rendered virtually in a 3D form and manipulated on a computer.

This data can even be sent to a printer to make oversized plastic models that scientists can play with to try to reconstruct the proper alignment of anatomical features which in the fossil itself may have been preserved in a jumbled heap.

For example, Ms Kruta uses a 15cm-long plastic print of a radula tooth to demonstrate the 2mm-long original that remains hidden away inside a fossil.

"For the radula you have to imagine a kind of band with something like 50 rows of teeth, and for each row you have nine teeth; and for some of the teeth you can have up to 17 cusps. It looks like a comb," said Dr Paul Tafforeau from the ESRF.

"In one of our specimens we found its last meal.

"The preservation meant we had both jaws in position with the radula, and then inside we had planktonic animals including one that had been cut in two. You can even see its internal organs," he told BBC News.

A jumble of radula teeth, each of which is only two or three millimetres in length. The X-ray techniques used at the ESRF allow scientists to virtually extract these features and even print physical models