Greenland glaciers spring surprise

- Published

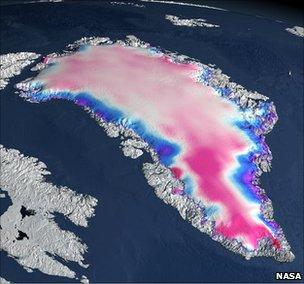

Nasa's IceSat saw thickening (pink) in places and thinning (blue) in others between 2003 and 2006

Some Greenland glaciers run slower in warm summers than cooler ones, meaning the icecap may be more resistant to warming than previously thought.

A UK-led scientific team reports the finding in the journal Nature, external, following analysis of five years of satellite data on six glaciers.

The scientists emphasise the icecap is not "safe from climate change", as it is still losing ice to the sea.

Melting of the icecap would add several metres to sea level around the world.

But it suggests that one reason behind the acceleration in glacier flow, which so concerned scientists when it was first documented in 2002, will prove not to be such a serious concern.

"In their last report in 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded they weren't able to make an accurate projection of future sea level because there were a couple of processes by which climate change could cause additional melt from the ice sheet," said Andy Shepherd from the University of Leeds.

"We're addressing one of those processes and saying that according to the observations, nothing will change, so that process can probably be ruled out."

In all five years studied (1993 and 1995-8), the speed of the glaciers increased with the onset of summer, as meltwater collected between the bottom of the glacier and the rock beneath, lubricating the flow.

But in the warmest years, the acceleration stalled early in the season; in relatively cool summers, it did not.

Even though the melting accelerated earlier in warmer years, by late summer the glaciers were 60% slower.

The explanation is that hotter summers cause so much meltwater to collect that it runs off in channels below the ice - meaning it does not lubricate the glaciers so efficiently.

Elevated concern

The results reinforce work by other scientific groups, on glaciers in Greenland and in mountains in temperate regions of the world.

And the somewhat counter-intuitive finding may change the view of what lies ahead.

Meltwater is not always an aid to glacier flow, the scientists deduce

"Those higher-temperature years are more like Greenland would be in 50-100 years," Professor Shepherd told BBC News.

"It's a snapshot of Greenland in the future; so one might expect the ice to be flowing slower than it is today."

However, this mechanism is not the only way that higher temperatures result in faster loss of ice.

Glaciers that end in the ocean can be accelerated by warmer seawater melting the ice tongue from underneath.

And warming can also lead to melting at progressively higher altitudes, increasing the total amount of water flowing down into the sea.

"I would be very careful about doing an extrapolation both in time and space," said Michiel van den Broeke, a polar icecap specialist from the University of Utrecht in The Netherlands and co-editor-in-chief of The Cryosphere journal.

"This ensemble of glaciers is quite small, and [the researchers] only take a limited elevation interval.

"So it's an important study, but it doesn't say what happens to glaciers higher up, and they could start acting like the accelerating glaciers now; so I'd be very cautious."

Satellite observations show an overall loss of ice across Greenland.

But thinning is greater along the coast and in the south, while some central areas have thickened, perhaps due to increased snowfall.

What happens to the crucial icecap when is still unclear; and may still not be resolved by the time of the next major IPCC assessment, in 2013/4.