Messenger probe enters Mercury orbit

- Published

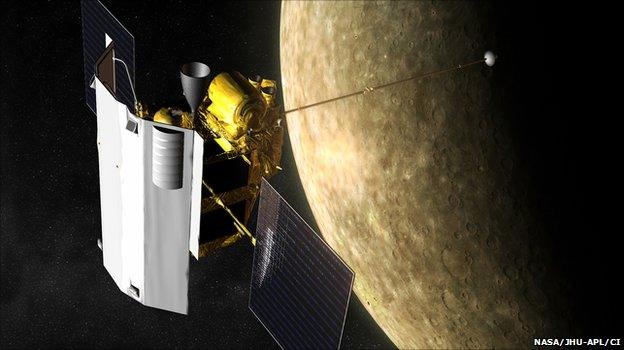

Messenger's ceramic shield protects it from direct heating by the Sun

Nasa's Messenger spacecraft has successfully entered into orbit around the planet Mercury - the first probe to do so.

The robotic explorer initiated a 14-minute burn on its main thruster at 0045 GMT on Friday.

This slowed the spacecraft sufficiently to be captured by the innermost planet's gravity.

Being so close to the Sun, Mercury is a hostile place to do science. Surface temperatures would melt lead.

In this blistering environment, the probe has to carry a shield to protect it from the full glare of our star.

And even its instruments looking down at the planet have to be guarded against the intense heat coming back up off the surface.

"It was right on the money," Messenger's chief engineer, Eric Finnegan, said. "This is as close as you can possibly get to being perfect.

"Everybody was whooping and hollering; we are elated. There's a lot of work left to be done, but we are there."

The spacecraft is now some 46 million km (29 million miles) from the Sun, and about 155 million km (96 million miles) from Earth.

Sean Solomon: "Mercury tests all of our ideas for how Earth-like planets form and evolve"

The orbit insertion burn by the probe's 600-newton engine will have parked it into a 12-hour, highly elliptical orbit about the planet.

Principal investigator Sean Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, is hoping for some remarkable discoveries in coming months.

"We started the Messenger mission as a proposal to Nasa 15 years ago," he told BBC News.

"We have been building for the orbit insertion and the observations that will follow for a decade and a half.

"To say that the science team is excited about what is to come is a huge understatement. We're really pumped."

Just getting to Mercury has proved a challenge.

Messenger has had to use six planetary flybys - one of Earth, two of Venus and three of Mercury itself - to manage its speed as it ran in closer to the Sun and its deep gravity well.

The strategy devised by scientists and engineers is to have Messenger gather data with its seven instruments during the close approaches (some 200km from the surface) and then return that information to Earth when the probe is cooling off at maximum separation from the planet (up to 15,000km from the surface).

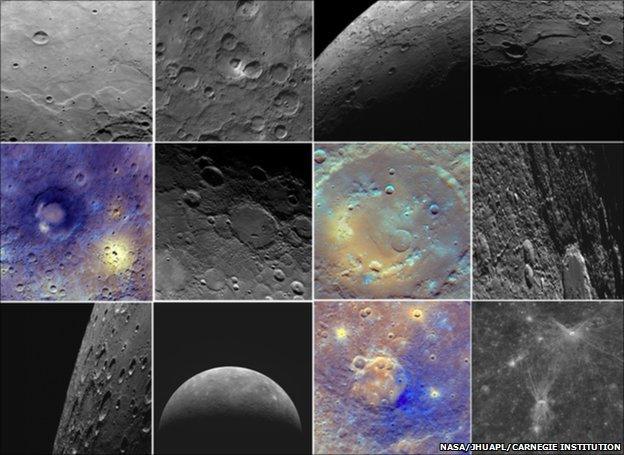

Images captured by Messenger have already revealed surprising details about the planet

Mercury is often dismissed as a boring, featureless world that offers little to excite those who observe it, but planetary scientists who know it well beg to differ. It is a place of extraordinary extremes.

Mercury's proximity to the Sun means exposed equator surfaces can reach more than 600C; and yet there may be water-ice at the poles in craters that are in permanent shadow.

It is so dense for its size that more than two-thirds of the body has to be made of an iron-metal composition.

Mercury also retains a magnetic field, something which is absent on Venus and Mars.

In addition, the planet is deeply scarred, not just by impact craters and volcanic activity but through shrinkage; the whole body has reduced in size through Solar System history.

And Mercury fascinates because it may be our best guide to what some of the new planets might be like that are now being discovered around distant suns.

Many of these worlds also orbit very close in to their host stars.

"We'll be looking at the composition of the planet and how it ended up so dense, and what planetary formation processes gave rise to the high fraction of core," said Dr Solomon

"The answer to that question lies in the composition of the surface that we can sense remotely from orbit, but we need time in orbit to do that.

"We'll also be taking more images, but images at higher resolution and in optimum lighting compared with the conditions we had during the flybys."

Others to follow

Key to the success of the whole endeavour will be maintaining the health of Messenger in the harsh conditions it will experience.

"The sunshade is made of a ceramic material that keeps the heat on the outside of the spacecraft from getting on the inside," explained Eric Finnegan, who is affiliated to the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL).

"We also had to develop thermal protection for the solar arrays. We still need to generate power but we had to make sure the solar arrays themselves wouldn't melt. So, we built a solar panel that's only populated with one-third solar cells. The other two-thirds of the panel are basically mirrors to reflect the sunlight off of the panels."

The spacecraft is scheduled to remain in orbit for a year, allowing the probe to fly around Mercury 730 times.

If Messenger stays in good health and the funding permits, a one-year mission extension is likely to be granted.

The European and Japanese space agencies (Esa and Jaxa) are also sending a mission to Mercury this decade.

BepiColombo consists of two spacecraft - an orbiter for planetary investigation, led by Esa, and one for magnetospheric studies, led by Jaxa.

Dr Solomon says there will be plenty left for the duo to do and discover when they get to the innermost planet.

"We'll be collecting global data on the surface, on the interior, on the atmosphere, on the magnetosphere - but we're not going to answer all the questions; we're going to raise new ones," he told BBC News. "There's going to be ample opportunity for follow-on missions."

- Published15 July 2010