UK shale plans target cheap gas

- Published

Shale gas has helped halve prices in the US market

Blackpool Tower, icon of an era when the fashionable spent summers in Britain, still stretches its elegant limbs towards the Lancashire clouds.

A few miles inland a gawky newcomer in the flat landscape makes a rival gesture towards the skies. It's a drill rig attempting to usher in an era of its own; an era of cheap and plentiful gas to set the UK's energy policy alight.

The land here in Lancashire's Fylde region was on the sea bed in the age of the dinosaurs. That was when the gas was formed, as fragments of organic matter ran off the hills, became squashed amidst grains of clay, and decayed. But the heavily-compressed shale rock trapped the gas molecules so tight that they can't escape into a conventional gas bore.

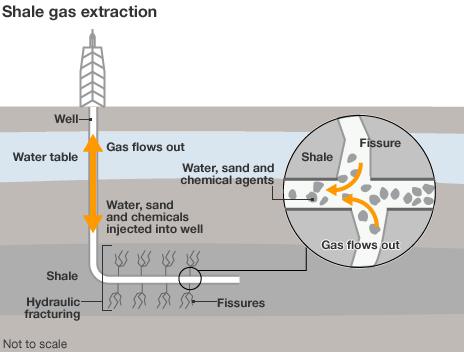

Now a controversial technique called fracking (fracturing) allows that gas to be extracted, by setting off small controlled explosions more than a mile below ground then pumping in water and lubricant chemicals to set the gas free.

At the pub in Singleton near the gas rig, the barmaid - along with other locals - was previously concerned by reports from the US that fracking has led to water pollution. But she's re-assured that the drillers spend time in her bar - and drink the tap water.

'Bullet-proof' well

"The rig doesn't really bother anyone," she told me. "It just looks like a piece of industrial equipment". The rig is actually a giant truck on wheels that gets clamped to the spot when drilling takes place. When it has done its job it will move to another site to drill again.

The firm involved, Cuadrilla, promise that their fracking technique is safe. Their CEO, Mark Miller is a veteran gas man from the US. He admits that careless fracking in his homeland has caused problems, but says: "People compare us to the worst operators in North America. Things are different over here because we use practices that are foolproof. We make a bullet-proof well where you can't get any leakages. It's called Industry Best Practice. We don't take any short cuts over here."

Fukushima and Deepwater Horizon have raised doubts about energy industry assurances on safety, and Cuadrilla's assertion is being put to the test by the Commons Energy Committee, which is investigating shale gas in the UK. The Energy Minister Charles Hendry is due to give evidence soon.

Cuadrilla currently have permission to do test drilling and the Environment Agency confirm that they will need to apply for a full licence if and when the time comes for full scale production.

Roger Harrabin shows how to get fuel from hard rock

Environmentalists want a delay in fracking until a major review of the practice by the US Environmental Protection Agency has been carried out - maybe sometime next year. The government believes its own safety regulations are strict enough.

So far, the Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) appears to be cautiously welcoming the advent of shale gas in the UK. Shale's not anticipated to supply a large proportion of Britain's gas needs, but it is contributing to a worldwide flow of gas that has halved gas prices in the US domestic market, and led to a glut in world markets.

At the moment, gas producers are succeeding in pegging global gas prices to oil prices but some analysts say this will have to change if gas remains in such plentiful supply compared with demand.

It adds spice to the UK's already piquant debate over future energy policy. While the world looks on with dismay at events in Japan, some lobbyists are pressing ministers to adopt gas with carbon capture and storage as a low-carbon substitute for nuclear. James Smith, chairman of Shell UK, told me he believed that gas with CCS would out-compete nuclear and wind power on cost.

"From being in a position of shortage before shale gas appeared on the scene the world is now in a position of plenty for 200 years. I believe that gas will play a very big part in the UK's energy scene for a very long time to come - particularly with ccs."

But the green lobby isn't taking fracking lying down. It's categorised fracking as a typically buccaneering technology employed by industry to extract resources first and look after the environment later.

Local backing

I met Philip Mitchell, chairman of Backpool Green Party by the banks of the picturesque River Wyre in this little-visited corner of rural England. "I'm worried about the risks," he told me.

"Risks to human health; to ground water and drinking water; and to the environment due to the huge amounts of waste this produces and the huge amount of water it consumes. Also I think the impact of drilling rigs on the countryside will be totally unacceptable to the British people. I think this is something we'll live to regret."

Fracking does indeed demand huge amounts of water - industries regularly do. But Cuadrilla has the backing of the local water company. It says it will dispose of drilling waste (cuttings) responsibly and ensure that no gas leaks into the water table. It says technology that involves lining the gas bore with concrete and steel will ensure that it is isolated from water supplies.

As to the issue of aesthetics, the drilling rigs are undoubtedly ugly - but when drilling is completed little is left behind except a gravelled field the size of a soccer pitch with a few bits of equipment.

Local planning requirements might compel these areas to be turfed over to restore the countryside - or even covered with a thin coat of soil and being turned into grassland for wildlife.

From what I have seen of the practice in the US, it would not be hard to screen the gas sites with trees - indeed that might be a requirement for planning permission too.

In the US, they have found that drill sites have to be placed much closer together than conventional gas wells, where the gas flows freely through the rock to the bore - the point of lowest pressure.

Cuadrilla say their tests show that the shale seam in Fylde is much thicker than the Royal Geological Society predicted - and they speculate that this might allow the effects of the fracking to spread over a wider area, reducing the demand for new drill bores.

I say speculate, because in an industry that works more than a mile underground, there is an inevitable element of ad hoc decision making. This is unpalatable to those environmentalists who want to control risks. It is up to the politicians to decide whether those risks are outweighed by the benefits of a second dash for gas.

- Published28 March 2011

- Published17 January 2011

- Published21 December 2010