Richard Branson's lemur plan raises alarm

- Published

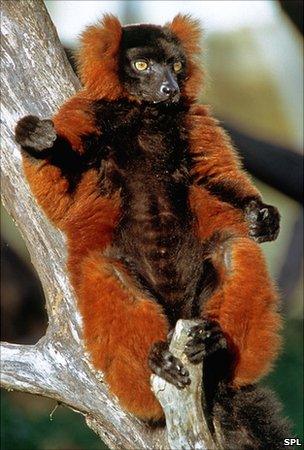

The red ruffed lemur is one of many sliding towards extinction, as logging proceeds

Sir Richard Branson is to import lemurs to the Caribbean, where they will live wild in the forest on his islands.

The project has alarmed conservation scientists, who point out that many previous species introductions have proved disastrous to native wildlife.

But Sir Richard's team maintains that both the lemurs, which will come from zoos, and native animals will be fine.

Introducing species found on one continent into another for conservation purposes is virtually unprecedented.

Lemurs are found only on the African island of Madagascar and many species are threatened, largely because of deforestation.

The threat has grown worse since the toppling of President Marc Ravalomanana's government two years ago, which allowed illegal logging to flourish.

"We've been helping to try and preserve lemurs, and sadly in Madagascar because of the government being overthrown the space for lemurs is getting less and less," Sir Richard told BBC News from his Caribbean property.

"Here on Moskito Island we've got a beautiful rainforest - we brought in experts from South Africa, and they say it would be an absolutely perfect place where lemurs can be protected and breed."

Ring-tailed and red ruffed lemurs are two of the species in the plan. Both are on the Red List of Threatened Species.

Moskito (also spelled Mosquito) Island is one of two that Sir Richard owns in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). Several luxury houses, including one for the boss of the Virgin business empire himself, are being built on it.

His other island is Necker, home to an eco-tourism resort where a stay is priced at around $2,000 (£1,200) per day.

The plan has aroused a lot of interest locally, with the bulletin boards of BVI news websites buzzing with comments for and against, and politicians locking horns.

And it concerned conservation scientists contacted by BBC News.

"Maybe [Sir Richard] has got some people to say it is all right - but what else lives on the island, and how might they be affected?" asked Simon Stuart, chair of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature's Species Survival Commission (IUCN SSC).

"It's pretty weird - I would be alarmed about it and would want some reassurances."

Dr Stuart suggested the project could contravene the IUCN's code for translocations, external - designed to prevent the repetition of disastrous events such as the introduction of rabbits and cane toads to Australia.

Among other things, it says that translocations should never happen into natural ecosystems.

When they do happen into areas that have already been altered by human hand, there should be a controlled trial period with continual assessment.

In the past, it says: "The damage done by harmful introductions to natural systems far outweighs the benefit derived from them".

Sifakas can jump, but not swim - still, some local people are concerned about them escaping

And Christoph Schwitzer, who co-ordinates the Madagascar work of the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, said the lemurs should really be kept in some kind of confinement.

"The project would only be acceptable if he intended to keep them in a controlled environment - that is, in some kind of fenced-in enclosure where they cannot become a problem to the native fauna and flora," he said.

"It's crucial that this move does not send the wrong message to people that it may be a good idea to keep lemurs as pets for their own personal pleasure."

And he warned that there could be impacts on local wildlife.

While some species of lemur are faithful to a diet of fruit, others will grab whatever is around, including lizards and other small animals.

"There may be birds nesting, and if there are some of the lemurs would attempt to predate on their eggs - or there may be small invertebrates that they'd go for," said Dr Schwitzer.

Necker and Moskito Island are home to reptiles such as the stout iguana, the turnip-tailed gecko and the dwarf gecko that local conservationists have identified as being of specific concern.

Sir Richard told BBC News that an environmental impact assessment had been carried out for Moskito Island; but critics in the BVI said it did not include evaluation of "introduced exotic species".

Sir Richard said that if it were seen that the lemurs presented any danger to local creatures, measures to protect them would be taken.

Welfare benefits

Sir Richard's motivation for wanting to introduce the animals is not entirely clear.

They seem unlikely to make a significant difference to his eco-tourism business.

Ring-tailed lemurs will be the first arrivals - adaptable feeders with a taste for bird eggs

One of his principal advisers is Lara Mostert, one of the managers of the Monkeyland Primate Sanctuary, a South African facility where many species of monkey and lemur live together in a patch of forest.

She said Sir Richard's lemurs would have a much better life than in the zoos where they currently live - some, she said, in "horrific" conditions.

"Unfortunately, primates have become rather like a business - the animals are seen as a commodity, and apart from that they don't really have an identity," she said.

"And that's one of the things I like about Sir Richard's plan - he's not going to sell them."

She thinks the animals will thrive on Moskito Island.

Sir Richard sees the project as bringing conservation benefits, envisaging that at some point in the future, lemurs could be reintroduced from Moskito Island to Madagascar.

But captive breeding programmes already exist for this purpose.

Despite the concerns, the plan has been approved by the BVI government and appears to be going ahead.

The first consignment, consisting of about 30 ring-tailed lemurs, is due to arrive within a few weeks, moved from zoos in Sweden, South Africa and Canada.

The much more imperilled red ruffed lemur may follow, possibly alongside some of the sifakas, famed for their calls and their jumping.

As threats to natural diversity multiply around the world, transporting species from place to place for conservation is one of the "extreme schemes" that conservationists are talking about and even beginning to implement.

But almost without exception, these translocations are taking place within the ecological region where the animal originated, rather than halfway across the planet.

- Published28 October 2010

- Published26 October 2010

- Published5 August 2010