Uranus image celebrates Herschel - the man and the machine

- Published

- comments

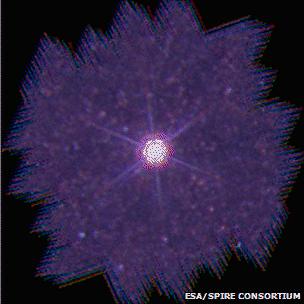

Uranus is too far away for the observatory to see as anything more than a very bright point of light

I've been on at the European Space Agency (Esa) to give us a picture of the Planet Uranus, external for quite a while, and I'm pleased to say the image has finally been delivered.

It was acquired by the Herschel Space Telescope, external and the release marks the observatory's second year in orbit.

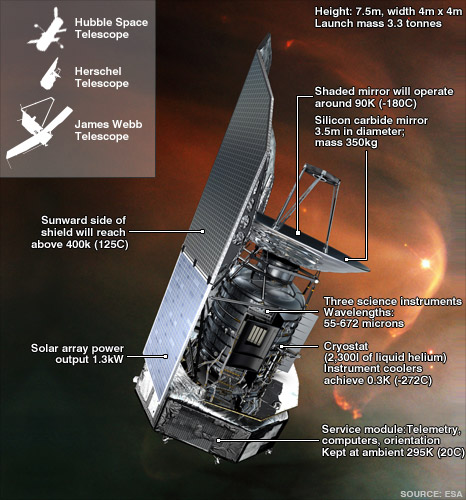

Europe's billion-euro astronomical marvel was launched on 14 May, 2009. It now sits over a million km from Earth, taking astonishing vistas of the cold and dusty cosmos.

Over the past two years, whenever I'd enquired about a Uranus picture, I was always told that it would be a pretty "boring blob of light", with little to commend it. "Glory in the main targets of the mission, Jonathan", was the message I received.

But the issue for me was one of historical significance. The far-infrared telescope is named after William Herschel, the 18th Century astronomer who - as we all know - discovered Uranus from his back garden in Bath in the west of England.

We needed a picture of the planet taken by the machine that now bears the great man's name. Simple and symbolic.

If you've never been to Herschel's house in New King Street in Bath, external, I can heartily recommend it. The place is now a museum dedicated to his life and to astronomy in general. You will get a chance to see his workshop and the tools he used to polish the mirrors for his telescopes.

These were dazzling machines in their day, and in many ways just as extraordinary as the Esa observatory called Herschel in his honour. People didn't believe at first that William Herschel could see the things he was claiming to pick out in the sky, but then his speculum mirror technology was so in advance of anything that had been produced at that stage.

He would really have appreciated the work that went into making the main mirror on Esa's telescope - itself a technological wonder.

At 3.5m, it is the biggest mirror ever flown in space. It was constructed from silicon carbide, external to maintain good shape while being as light as possible. It's done its job perfectly.

So what of our eagerly awaited picture of Uranus? Well, the shot illustrates some fascinating detail about both the performance and the construction of Esa's flagship space telescope.

Uranus is too far away for the observatory to see as anything more than a very bright point of light, but it's certainly not a boring blob.

The spikes you see coming off "George's Star" are a consequence of the telescope's optics.

Its secondary mirror, which sits in front of the big primary reflecting surface, has a series of support legs, and it's their presence which produces these spikes.

It's not unlike what you've probably encountered with your own camera when you orientate its lens towards a very bright, point-like source such as the Sun. You'll also get some streakiness because of the optical design.

But look beyond Uranus for a moment and you will see a swathe of blue dots. They're actually all distant galaxies - each and everyone a mass of stars, millions to billions of light-years more distant than the seventh planet in our Solar System.

Cardiff University's Professor Matt Griffin is the principal investigator on Herschel's SPIRE (Spectral and Photometric Imaging Receiver) instrument, one of the three instruments in the telescope and the one responsible for the Uranus picture. He told me:

"I like the picture, too. It illustrates perfectly what the telescope was set up to do, because it is exactly as it should look. We look at the planet quite often. We use Uranus as a calibration tool.

"As in most astronomical observations, we use standard sources - sources whose brightness and spectra we understand very well - as calibration standards. And basically we compare everything else with respect to them.

"In the case of the SPIRE spectrometer, Uranus is a perfect source to do that because we know exactly how big it is, we know exactly how bright it is, and we understand its spectrum very well. Very importantly for us, its spectrum is nice and smooth and featureless in our wavelength range, so that we don't get any artefacts when we compare other sources to it.

"And then of course you can see all the galaxies in the background. It's very unusual in astronomy to have such a large dynamic range in an image where you can see a very bright source and a very faint source in the same picture; but that's Herschel."

When we were making our documentaries on the Herschel Space Telescope for BBC Radio, myself, Matt and Bruce Swinyard from University College London (a key figure in SPIRE's development) visited Herschel's house in Bath to look at the tools he used to fabricate his mirrors.

The sequence we recorded in the workshop didn't quite make it into the finished programmes, but I've included it on this page. Enjoy, and thank you Esa for finally giving me Uranus.

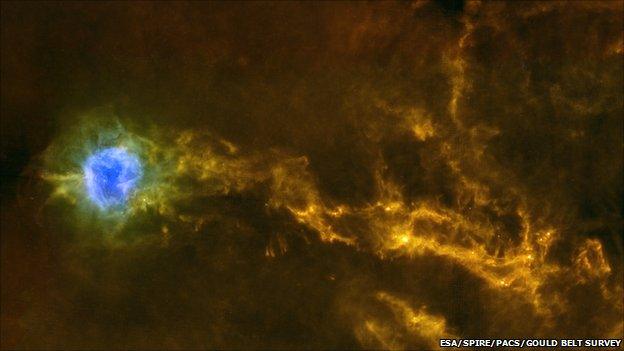

Herschel's day job: Imaging cold filaments of gas and dust, as here in a star forming region in the constellation of Cygnus. Herschel's mission is to help us understand how stars come into being

- Published4 January 2011