Fukushima 'lessons' may take 10 years to learn

- Published

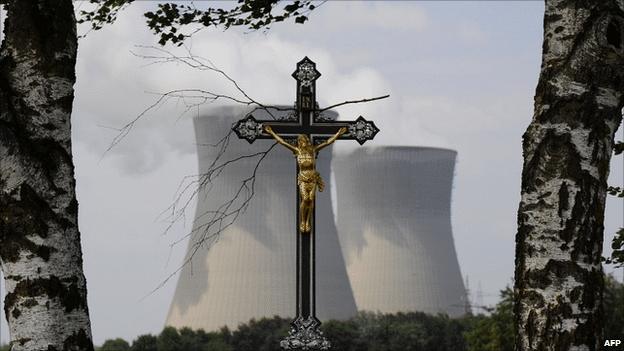

Germany plans to close its nuclear stations in just over a decade - which has brought Czech derision

Learning all lessons from the accident at Japan's Fukushima nuclear power station could take a decade, according to France's top nuclear safety officer.

But all nuclear countries should carry out safety tests within a year, said Andre-Claude Lacoste.

The chairman of the French nuclear safety agency (ASN) was speaking at a forum in Paris organised by the OECD's Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA).

Regulators said international control of nuclear safety would be "difficult".

The forum follows a day of political discussions on nuclear safety organised by the French G8 presidency, and comes two weeks before ministers gather in Vienna for a week-long session at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that could set new international rules.

Fragmented picture

"Fukushima was a shock," Mr Lacoste told reporters at a news conference.

"We have to draw lessons from it - and drawing lessons from Fukushima could take up to 10 years, referring to the time it took to draw lessons from Three Mile Island and Chernobyl.

Germany's Metropolitan Opera stars pulled out of a Japan tour, citing radiation fears

"But this shouldn't prevent us from doing what needs to be done as soon as possible."

However, Gregory Jaczko, chairman of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), said 10 years was too long.

"Ten years is a reasonable timeframe based on previous experience," he said.

"But I think we need to challenge ourselves to learn in a faster timeframe - we should do better."

Earlier this week, Japan's nuclear regulator issued a report admitting that the country had been ill-prepared for an accident as serious as the one at Fukushima Daiichi.

It also doubled estimates of the amount of radiation released following the 11 March tsunami.

But Mike Weightman, the UK's chief nuclear inspector, said the picture of what had happened inside the reactors was still far from complete.

"It's very difficult to understand what the situation was inside the reactors in the early days," he said.

"Now they've been able to do some theoretical modelling, but they still haven't been able to go inside, and so the picture may change - with Three Mile Island, it took some time to find out what the real situation was inside."

Blurred transparency?

At the G8 meeting and the NEA forum, one of the issues under discussion has been how nuclear safety should be internationalised.

Switzerland's Energy Minister Doris Leuthard, whose government has just voted to close its nuclear stations within 25 years, said countries should have the right to inspect their neighbours' safety plans.

"Why don't we accept that peer reviews should be mandatory?" she asked earlier this week.

But the regulators at the NEA forum said this would be difficult.

"There's a strong view in the US that it's important for countries to participate in [existing international peer review] processes, that they're valuable," said Mr Jaczko.

"But I think making this mandatory is something that would take a long time and require some kind of international instrument, whether a treaty or some other kind of vehicle."

In many other countries, the civilian nuclear industry began its life under military constraints, and it is likely that measures requiring complete transparency would be unnacceptable to a number of nations including the US, Russia and China.

For politicians in Switzerland and Germany - where nuclear reactors are likely to close by 2022 - the irony is that they will still be able to buy nuclear electricity from their neighbours, without having any jurisdiction over plants close to their borders.

Speaking in Germany on Tuesday, Czech President Vaclav Klaus described the nuclear exit as "absurd", and said his government intended to expand its Temelin plant, situated about 60km from German territory.

'Remarkable' action

As the situation at Fukushima continues to develop, Mr Weightman - who has just visited the site on an IAEA fact-finding mission - paid tribute to workers who had battled to gain control of the stricken plant in the days following the tsunami.

"The way in which they dealt with the aftermath of the incident was very impressive," he said.

"It was dark, they'd lost all power, they'd lost instrumentation, they'd lost air with which to control valves, and they were having to control six reactors and spent fuel ponds with very little hope of external assistance.

"They did some remarkable things under very difficult circumstances, and I'd be surprised if others could do better."

Swift government action to evacuate people around the plant and subsequent monitoring of their exposure had also been "superb", he said.