The excitement of 'new space'

- Published

- comments

The Cygnus spacecraft is part of Nasa's new approach to low-Earth orbit operations

Like all would-be space entrepreneurs, David Thompson needed a big idea to get his business going.

Having worked on the development of the shuttle, he thought there might be something interesting one could usefully do with the vehicles' giant external fuel tanks, external.

These behemoths are dumped once the orbiters have made it into space and fall back into the atmosphere to be destroyed.

Thompson's brainwave was to push them into orbit, also.

His vision was for them to be filled with water. Over time, the tanks would then use electrolysis to split the liquid into hydrogen and oxygen - to produce yet more rocket fuel. A "gas station in the sky".

"There were a number of problems with this idea," Thompson recalls with a grin - "the number one being that there weren't that many rockets coming along this road where our gas station would be."

Undeterred, he simply moved on to his next concept.

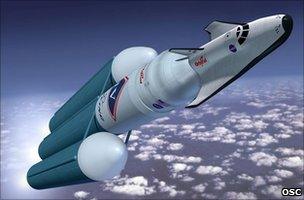

The Pegasus rocket is dropped from an aeroplane before igniting its engine

This was a booster module that would carry a satellite deployed from the shuttle into its correct orbit high above the Earth. This time, the spark caught hold and our space entrepreneur was off and running.

The Transfer Orbit Stage, external was the first product of the Orbital Sciences Corporation, now of Dulles, Virginia, external, the company set up by Thompson and two friends.

Today, there are no mad-cap ideas - just solid business practice that has turned the company into an established player in the space market, and one that now aims to play a significant role in the new commercial approach to human spaceflight being adopted by Nasa.

I caught up with David Thompson in London where he was being presented with an Sir Arthur Clarke Award for International Space Achievement, external.

Sir Arthur, he told me, had been a major inspiration and receiving the award was a big thrill:

"We've been in business for over 29 years now but go back twice as many years and Sir Arthur was anticipating many of the technological innovations and practical applications of satellite technology that we've now had the chance to develop.

The Orbital-built Dawn probe is bearing down on the Vesta asteroid

"It's amazing how many of his projections have become fact. For example, he projected communications and broadcasting would be the biggest commercial applications of space, and here we are today with - depending on what you count and how you count it - $100-150bn a year tied up in that business. He was astonishing."

For those who don't follow space matters closely, Orbital may not be as familiar a space name as, say, Boeing or Lockheed Martin. But the Dulles outfit has built a formidable reputation.

Its mainstays are rockets and lightweight satellites. To date it has launched about 700 of the former and built and delivered around 150 of the latter.

Perhaps, Orbital's best known launcher is Pegasus - an innovative booster that is carried to altitude by an aeroplane before firing its own engine to get above the atmosphere.

And listen out for Dawn, an OSC satellite that will make big news in the coming weeks. Dawn, which was constructed for Nasa, is fast approaching Vesta, a giant asteroid. The pictures it sends back to Earth are sure to be plastered all over the newspapers and the internet.

It's an interesting moment to be talking to David Thompson. In his younger days he spent some time working inside Nasa, but then went outside the agency to see if there was a different way to do space other than through Big Government. And in one sense, Nasa is now catching him up.

The Transfer Orbit Stage was more practical than a 'gas station in the sky'

Once it retires its shuttle fleet following the final mission of Atlantis this month, the agency will be hiring OSC and other companies to service the International Space Station (ISS). Just as an organisation might contract an external provider to do its payroll or IT, so Nasa is going to contract private companies to ferry astronauts and cargo to and from the ISS.

OSC has teamed up with Thales Alenia Space (Italy) to build a robotic freighter called Cygnus, external. It won't have anything like the mass-carrying capability of a shuttle but the supplies it brings to the station will be critical to the outpost's future operation.

Its contract with Nasa is for a fixed price. Gone is the agency's old way of doing business which saw it pay companies what it cost to do the job, with a bit extra on top. Under the new arrangement, Orbital has to meet certain milestones to get its payments. If it doesn't make the grade, there'll be no cheques arriving in Dulles.

"I find it exciting and enlightened that a government agency that pioneered this area more than any other single organisation should conclude that the private sector is ready for this responsibility," said Thompson.

"It's not going to be without its difficulties and challengers but space has always been that way. It's an approach I believe will ultimately succeed and allow Nasa to invest its funds in more advanced missions that go to deep-space destinations."

Right now, the first Cygnus is being assembled and should be flying within months. First, however, there is the small matter of proving the rocket that Orbital intends to use to loft Cygnus. Called the Taurus II, it will make a maiden flight towards the end of the year.

Orbital's proposal for a shuttle-like vehicle to take crew to the ISS did not win over Nasa

Not everything has gone exactly to plan: a development engine caught fire whilst on a test stand in June. Indeed, there's been a few knocks of late for Orbital. In March, it lost the Glory climate satellite when an Orbital rocket malfunctioned just minutes into its flight. Tough lessons, according to Thompson: "Having launched the number of rockets we have and made the number of satellite we have - we know such problems can be identified and solved, and that we can move on and be a little smarter next time."

Cygnus is an unmanned ship but Orbital has drawn up plans for a small shuttle-like vehicle it thinks could ferry astronauts to the ISS, also. Unfortunately for Orbital, Nasa has decided to invest in other companies' designs for human transportation. Thompson, though, hasn't ruled out competing again at a later date.

"The level of demand over the next decade for commercial astronaut transportation is probably not sufficient to support more than two, and possibly only one, operator," he told me.

"If Nasa has decided to focus on other areas, we may just have to take a pass this time around and continue to watch how things evolve."

David Thompson's Sir Arthur Clarke Award was formally announced at the UK Space Conference, external on Monday night in Coventry.

I'm afraid neither the OSC chairman nor this correspondent could be present in person. My excuse is that I've made the trip out to Cape Canaveral to watch the final launch of Atlantis - to see the baton being passed from "old space" to "new space".