A world built on ice and whales

- Published

- comments

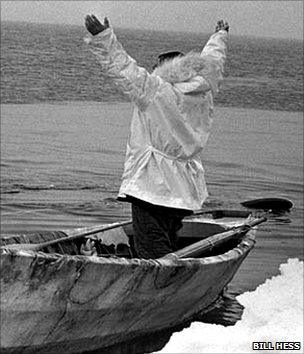

Whaling captains give a prayer of thanks when they have "received" a bowhead whale

From the International Whaling Commission (IWC), external meeting in Jersey:

At the northern end of the populated world, a kind of whaling goes on that is the polar opposite of the industrial-scale, mechanised harvesting that brought several species close to the brink of extinction in decades gone by.

Around the Arctic rim, peoples such as Inuit and Inupiat catch whales for eating, and a few other uses, within their local communities.

Aboriginal subsistence whaling (ASW), external - or indigenous subsistence whaling, as it's to be known in future - is not without its critics.

Some object on the grounds that it's still killing whales, and therefore wrong.

Others point to the fact that whales take longer to die on average in subsistence hunts than in the commercial variety, so it's more cruel.

Yet more ask whether the communities in question really need the meat, in the 21st Century as we are, especially if they live in nations that are either rich, such as the US, or shortly to be so, in the case of Greenland.

Interestingly, some on the pro-whaling side - Iceland, Japan, Norway, and others - share the criticisms, arguing that whale hunting is whale hunting, wherever it happens and who does it, and that indigenous groups should get no special treatment.

A few years ago, I visited the Alaskan town of Barrow, external, which is so far north that virtually nothing will grow in the ground, and ice is more common underfoot than anything approximating to soil.

I talked about whaling and the bowheads that pass the coast twice a year on their annual migration, but wasn't able to meet the community's leading lights, as they were away at the time lobbying for the right to continue their tradition.

With ASW up for review again at next year's IWC meeting, they're now in Jersey - so we took the chance, over a lunch table that bore no whalemeat, to have the discussion that I'd have liked to have four years ago.

Structural integrity

The Brower family is one of Barrow's oldest, and has produced a stream of whaling captains, including Harry and Eugene, both imposing-looking men with whom you would not want to tangle.

Harry currently chairs the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission (AEWC), external, while Eugene leads a team looking specifically at weapons issues.

Johnny Aiken is AEWC executive director, and George Noongwook the vice-chair.

For a small organisation, it seems therefore to have a lot of structure; and indeed, the notion of social structure ran right through our conversation.

Each whaling captain carries real status in the community, which means rights as well as responsibilities.

In charge of the whaling boat's operations, the principal responsibility is to provide whalemeat for his crew, his family and the extended community.

It's not quite as vital for nutrition as it once was, because now most of the 11 whaling villages do have food stores, and many people have paid jobs.

But it's still clearly a major aspect of life. Not only bowhead whales but seals and fish are caught for food, with some being bartered with other indigenous groups inland in return for caribou meat.

The diet of virtually unexpurgated meat would give a Western dietician nightmares, but it clearly works fine for the Inupiat.

The whale is butchered on the ice edge, and the meat apportioned

I asked about the importance of whales now as a source of food.

It proved a difficult question to answer - George explained, for example, how whale oil might be used for flavouring in dishes that were not made of whalemeat, such as caribou soup - and about the closest we could get is that on average, people will eat whalemeat a couple of times each week.

Traditionally, the meat is kept in caves dug into the permafrost, although climate change appears to be taking a toll.

Eugene explained that whereas meat would keep virtually indefinitely a few decades ago, now it won't - temperatures are too high in summer - and several communities have invested in Western-style chest freezers.

Warming has also changed hunting habits.

Traditionally the sealskin boats - quiet and stealthy - pushed out in April.

Now, a fair bit of the hunting - 40%, in the case of George's southernmost village of Savoonga - is done in November and December, as the bowhead whales return south.

At this point in the year, the ice is so tough as to wreck sealskin boats, so materials such as aluminium are used instead.

The whales appear to be fatter than in the recent past.

Craig George, a scientist based in Barrow, has correlated records going back into the last century, and believes the whales do better in warmer years with less ice, perhaps because they can stay longer in the northern feeding grounds.

And the Inupiat say the feeding season is now a couple of weeks longer than it used to be.

Whether the whales will continue to get fatter as the ice melts further, or whether the trend will reverse, is another matter.

Respecting tradition

Technology and enhanced scrutiny over welfare issues have also changed the hunt, with modern explosive harpoons used - the idea being to kill the animal as quickly as possible - ideally, instantaneously.

Not that the Inupiat themselves use the term "kill".

And here is where the real insights begin, taking you into a world with mores and values a world away from modern, Western-style existence - a marked contrast in particular with mainstream US cultures of speed and instant opportunities and individualism.

Harry Brower explained the Inupiat belief that a whale comes ashore in human form as the boats' crews gather to discuss the coming season's hunt.

If the whale/human hears anything disrespectful, they will not allow themselves to be caught - and, he added, there are some captains who have been hunting for years without ever catching a thing, the implication being that they were not respectful enough.

The crews "receive" their whales from the sea, with the captain giving a prayer of thanks immediately afterwards.

Hauling out the whale, and butchering it, are people-intensive tasks

Like the early Japanese whaling, swathes of people are needed to haul the whales up onto the ice, butcher it and prepare food, with an immediate delicacy being the "muktuk" - the blend of blubber and skin, eaten raw.

The meat, blubber, internal organs, skin, and flippers are apportioned between those on the ice, the crew, and the captain - but the captain is then responsible for sharing that meat around the community in the next few months, with festival days prominent.

And you can't become a captain in a hurry. Purely from a survival point of view, Eugene explained, you have to learn the signals of moving ice and currents and winds, with polar bears a regular hazard.

Get that wrong in the old days, and the crew died - although nowadays search and rescue helicopters can be called in.

Still, boys (and increasingly, girls) have to work up from the bottom. The Browers's first tasks were washing up and preparing tea and coffee; and there are crewmen in their 40s complaining they are not yet captains.

When you do make it to captain, you are considered a "true person". Captains' wives, too, hold a pivotal and powerful place in society.

In the Alaskan hunts, none of the meat is sold - although there are carvers who make trinkets from bones and baleen, some selling for many hundreds of dollars.

Cash concerns

Not all ASW hunts have been free of commercial taint.

Three years ago, the World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA) found that about a quarter of whalemeat from the Greenland Inuit hunts, external, for example, found its way into supermarket chains, where it could be bought by anyone, not just the indigenous people for whom it was intended.

For this reason, and the others I noted at the top of this post, some would like the IWC to consider the issue of ASW far more critically than it has done in the past.

For my lunch companions, ending the hunt is not to be contemplated.

The community coheres around whaling, and the communal nature of the hunt gives structure to the society - that's one aspect of their argument.

But they also argue that they provide the best defence for the whales against developments that could seriously harm them, such as oil and gas exploration.

Inupiat society and values clearly appeal to some westerners.

In Barrow, I met a number of people from the US mainland (the "contiguous 48 states", as they say) who had chosen to live there despite the harsh weather, the months without sunlight, the absence of luxuries in the stores and the very different societal structure.

And they defended whaling to the hilt, even those who had previously imagined they would be against it, because they saw it as the society's foundations; remove the whaling, and one of the few indigenous cultures to endure relatively intact in the western world would collapse.

Is that more important than the whales themselves, or less? And are the whales better or worse off because the hunters are there?