Fessenheim: Splitting the atomic world

- Published

The twin reactors of the Fessenheim plant draw their cooling water from the Rhine Canal

The Rhine Canal is placid in the afternoon sun.

Barges saunter by, insects buzz, and the occasional bird makes a foray from the marshier banks of the Rhine itself, a kilometre away.

But the tranquil ambience is misleading. Here lies a new fault line, one that spans much more of the globe than Europe; the line that marks the division between nuclear and anti-nuclear ambitions.

The centre of the issue is Fessenheim nuclear power station, whose twin reactors, reflected in the water's still surface, are the oldest in France.

French safety regulators have just recommended that one of the reactors can continue to operate for another decade, and a similar recommendation on the other is expected later in the year.

On the other side of the Rhine is Germany, which decided earlier this year, in the wake of the Fukushima disaster in Japan, to phase out nuclear power within that same decade.

German local authorities, and many citizens nearby, want Fessenheim closed too and are angry that they have no say in the matter, despite the fact that the station sits just 1.5km from their border.

Switzerland, 40km further south, wants the same thing. Both see a future powered by Sun and wind, not the atom.

As the world decides which path to take in the aftermath of Fukushima, you could not find anywhere on the planet where the nuclear divide looms so large.

Fessenheim has seen many protests recently, but is likely to stay open

Fessenheim has always been controversial.

Even before its completion in 1976, protests ran long and loud in France, as well as its neighbours.

Campaigners lived in a pylon for nine months; they also set up a pirate radio station broadcasting anti-nuclear information, using a portable transmitter carried from place to place in the hills nearby to avoid detection.

Since its opening, however, the station has had no significant accidents. So why not conclude that it is safe?

"Fukushima also worked safely for 30 years," responds Axel Mayer, who leads the branch of environmental group Bund in nearby Freiburg, known as the ecological capital of Germany.

"But now, after Fukushima, we see things differently; and if we have an accident in Fessenheim, the radioactive water won't go into the ocean, it'll go into the Rhine, and then it's not a problem of the area, it's a problem of Europe."

In part, opposition to the ageing station is based on the general arguments against nuclear power; the danger of weapons proliferation, the lack of a solution to waste disposal, and so on.

But there are some aspects of Fessenheim that make it a particular target.

In 1356, a major earthquake destroyed the city of Basel, just over the Swiss border.

This is a geologically complex area, and the cause of the Basel quake has not been precisely pinned down; but the design requirements for Fessenheim did not specify that it must resist an event of similar magnitude nearby.

In fact, its concrete base is one of the thinnest of all European nuclear stations - a point picked up by the French regulators, who insist it must be strengthened in order to gain the extra decade of operating life.

In addition, it lies below the level of the canal water, and there are fears about flooding if the levee were damaged - fears that to some campaigners resonate with echoes of Fukushima.

But not to Fabienne Stich, the mayor of Fessenheim town.

"We sought expert evaluations," she says.

"Ecologists and anti-nuclear campaigners say the dam might break - fine, it could - but if that happened, the water would drain onto the plain and it wouldn't be a great wave over the power station like in Japan - that's not possible."

Carbon concerns

The French government argues that the nuclear industry is good for the country economically, generating employment and exports along with clean, reliable electricity.

Nuclear fission produces about 80% of French electricity, and companies with big stakes in the industry such as EDF and Areva are mainly state-owned.

Locally, the Fessenheim power station is obviously important economically, employing 700 people, many of whom are highly skilled.

I spoke to a few residents in the local pharmacy, where they must come every four years to pick up supplies of iodine tablets in case of a radioactive release.

The general view was that the station was OK with them - nothing serious had happened. "How else are we going to get our electricity?" was a point frequently made.

It is made also by Jerome Stiebel, a medical physicist from the University of Strasbourg in France and a member of the organisation EFN - Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy.

"I think nuclear power is ultimately the least dirty option," he says.

"If you look at Germany that wants to abandon nuclear power, or at the Swiss, what are they going to do?

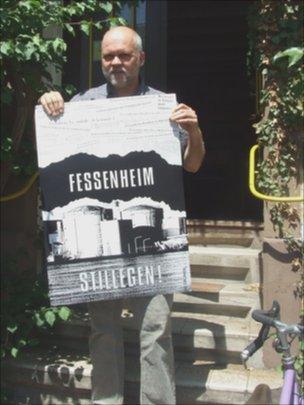

Axel Mayer: "Nein" to Fessenheim

"They're going to replace it with gas and coal, and put tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere."

For all its environmental credentials, Germany uses fossil fuels for about two-thirds of its electricity generation - three times as much as France - and is building new plants burning coal and gas.

Since closing eight nuclear stations earlier this year, it has been importing more electricity from France and the Czech Republic via the cables that tie the European grid together - and that is largely nuclear electricity.

The eventual German ambition is to replace all of it with renewables, and the policy's architects believe phasing out nukes with speed and certainty is the way to advance the renewables vision.

"The renewable energy community has argued that what is needed is a rapid phase-out, because then it's clear that money needs to be invested in a new grid infrastructure, in building offshore wind parks," argues Miranda Schreurs, director of the Environmental Policy Research Centre at the Free University of Berlin.

"As long as those nuclear plants are allowed to run, it leaves the door open to a change of policy towards further extensions to their lifetime or perhaps eventually a build-out of nuclear power, which makes it difficult for investors to say 'OK, I know now where I'm going to put my investment - into renewables'."

But Ralf Gueldner of energy giant E.on, president of the nuclear trade body Foratom, says that is wrong.

"The plan in Germany was to have some 35% of power produced by renewables by 2020," he recalls.

"But who's going to invest? Where does the money come from?

"Part of it should come from revenues out of the operation of the nuclear power plants; so the question is, will there now be enough money available to invest in renewables?"

Breaking the 'wall'

As things stand, the Franco-German energy divide is starker than ever before, with each embarking on very different trajectories.

In France, some observers believe Germany is heading down an expensive blind alley and will revisit the nuclear question at some point.

But others believe it is showing the way forward for the world by ending the nuclear age; and the campaigners who are opposing Fessenheim by what they describe as "the methods of Gandhi" are determined to change French national policy.

"France is putting all its hopes into the nuclear industry, it boasts of being the leading manufacturer of nuclear power stations, and it's so well established at the industrial and political levels that we're under the yoke of the nuclear lobby," says Claude Maillet.

"I use this image comparing it to the Berlin wall - we're up against a wall of French nuclear power, and each citizen, each activist, should pick up a tool and strike the wall of nuclear power, and we'll be able to bring it down."

You can hear more about Fessenheim, the European microcosm of the global nuclear divide, in Atomic States on the BBC World Service

- Published11 July 2011

- Published1 July 2011

- Published25 April 2011