Earth may once have had two moons

- Published

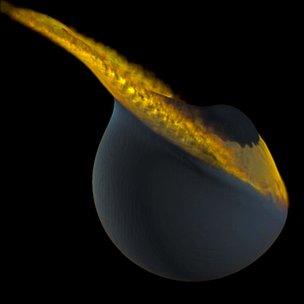

The collision would have occurred at a relatively low speed, say the scientists

A new theory suggests the Earth once had a small second moon that perished in a slow motion collision with its "big sister".

Researchers suggest the collision may explain the mysterious mountains on the far side of our Moon.

The scientists say the relatively slow speed of the crash was crucial in adding material to the rarely-seen lunar hemisphere.

Details have been published in the journal Nature, external.

The researchers involved hope that data from two US space agency (Nasa) lunar missions will substantiate or challenge their theory within the next year.

For decades, scientists have been trying to understand why the near side of the Moon - the one visible from Earth - is flat and cratered while the rarely-seen far side is heavily cratered and has mountain ranges higher than 3,000m.

Various theories have been proposed to explain what's termed the lunar dichotomy. One suggests that tidal heating, caused by the pull of the Earth on the ocean of liquid rock that once flowed under the lunar crust, may have been the cause.

But this latest paper proposes a different solution: a long-term series of cosmic collisions.

The researchers argue that the Earth was struck about four billion years ago by another planet about the size of Mars. This is known as the global-impact hypothesis. The resulting debris eventually coalesced to form our Moon.

Slow-motion impact

But the scientists say that another, smaller lunar body may have formed from the same material and become stuck in a gravitational tug of war between the Earth and the Moon.

Dr Martin Jutzi from the University of Bern, Switzerland, is one of the authors of the paper. He explained: "When we look at the current theory there is no real reason why there was only one moon.

"And one outcome of our research is that the new theory goes very well with the global impact idea."

After spending millions of years "stuck", the smaller moon embarked on a collision course with its big sister, slowly crashing into it at a velocity of less than three kilometres per second - slower than the speed of sound in rocks.

Dr Jutzi says it was a low velocity crash: "It was a rather gentle collision at around 2.4km per second; lower than the speed of sound - that's important because it means no huge shocks or melting was produced.

At the time of the smash, the bigger moon would have had a "magma ocean" with a thin crust on top.

The scientists argue that the impact would have led to the build-up of material on the lunar crust and would also have redistributed the underlying magma to the near side of the moon, an idea backed up by observations from Nasa's Lunar Prospector spacecraft.

In a commentary, Dr Maria Zuber from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, US, suggests that while the new study "demonstrates plausibility rather than proof", the authors "raise the legitimate possibility that after the giant impact our Earth perhaps fleetingly possessed more than one moon".

The researchers believe one way of proving their theory is to compare their models with the detailed internal structure of the moon that will be obtained by Nasa's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

They will also be looking to high resolution gravity mapping set to be carried out next year by the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission.

But according to Dr Jutzi the scientists would prefer to get their hands on samples from the far side of the Moon to prove their theory.

"Hopefully in future, a sample return or a manned mission would certainly help to say more about which theory is more probable."

- Published5 June 2011

- Published22 October 2010