Darkest exoplanet spotted by astronomers

- Published

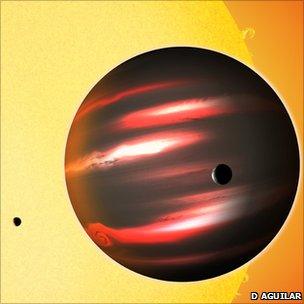

TrES-2b is literally darker, on average, than coal

A dark alien world, blacker than coal, has been spotted by astronomers.

The Jupiter-sized planet is orbiting its star at a distance of just five million km, and is likely to be at a temperature of some 1200C.

The planet may be too hot to support reflective clouds like those we see in our own Solar System, but even that would not explain why it is so dark.

The research, external will be published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The planet, called TrES-2b, is so named because it was first spotted by the Trans-Atlantic Exoplanet Survey in 2006. It is about 750 light-years away, in the Draco constellation.

It also lies in the field of view of the Kepler space telescope, whose primary mission is to spot exoplanets using extremely sensitive brightness measurements as far-flung worlds pass in front of their host stars.

Using the first four months' worth of data from Kepler, David Kipping of the Center for Astrophysics at Harvard University and David Spiegel from Princeton University, looked at the amount of light coming directly from TrES-2b itself.

They measured the amount of light coming from the planet's "night side" - when it is directly in front of its star. They compared that to the light coming from its "day side", just before it passes behind its star and Kepler sees it bathed in light.

The difference between the two gives a measure of how much light the planet reflects - or its albedo.

In our Solar System, clouds on Jupiter give it an albedo of 52%; Earth's is about 37%. But it appears that TrES-2b reflects less than 1% of its star's light.

"This albedo is darker than that of black acrylic paint or coal - it's weird," Dr Kipping told BBC News.

'Exotic chemistry'

The explanation may simply be that the planet is too hot to support the reflective cloud cover we see in our own Solar System.

However, both Dr Kipping and Dr Spiegel said even that would not explain why TrES-2b is such a dark world. It is not just that the planet is failing to reflect light; something must be absorbing it.

"Chemicals such as gaseous sodium and titanium oxide have been proposed to have this effect," Dr Kipping told BBC News. "Whilst it is possible that there is a huge overabundance of these chemicals, it is probably more likely that there is some exotic chemistry going on which we have never seen before."

Jonathan Fortney, an exoplanetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, called the work "a nice paper" because "Kepler is allowing us to see these tiny signals from 'hot Jupiters'".

A large fraction of the planets that have been identified in other solar systems are these "hot Jupiters", but little is yet known about them other than their size and proximity to their host stars.

"What will be very interesting is the detection of hot Jupiter reflectivities for different planetary temperature and surface gravities, because that will tell us what planets can keep clouds suspended and what the cloud material might be," Dr Fortney told BBC News.

Much more of the story will be laid bare when more data from the Kepler telescope is put to the test, and when more is released, said Dave Latham, a co-investigator on the Kepler project.

"There are much better data now, from more than two years on orbit, but not yet released to the public," Dr Latham told BBC News.

"A batch of new and higher-quality data is scheduled for release on 22 September. That should allow an improved detection of the (reflectivity of) TrES-2."

- Published2 February 2011

- Published3 February 2011

- Published8 April 2011

- Published14 June 2011

- Published17 May 2011

- Published20 April 2011