Species flee warming faster than previously thought

- Published

Warmer weather has brought the British comma dancing around Scottish nettles for the first time

Animals and plants are shifting their natural home ranges towards the cooler poles three times faster than scientists previously thought.

In the largest study of its kind to date, researchers looked at the effects of temperature on over 2,000 species.

They report in the journal Science, external that species experiencing the greatest warming have moved furthest.

The results helped to "cement" the link between climate change and shifts in species' global ranges, said the team.

Scientists have consistently told us that as the climate warms we should expect animals to head polewards in search of cooler temperatures.

Animals like the British comma butterfly, for example, has moved 220km northward from central England to southern Scotland in the last two decades.

An uphill struggle

There is also evidence that more species seem to be moving up mountains than down, explained conservation biologist Chris Thomas from the University of York, UK, who led the study.

But studies had stopped short of showing that rising temperatures are responsible for these shifts in range, he added.

Now he and his team have made this link.

Species at the summit of Mt Kinabalu in Borneo may be doomed if temperatures rise further

Analysing the range shifts of more than 2,000 species - ranging from butterflies to birds, algae to mammals - across Europe, North and South America and Malaysia over the last four decades, they show that organisms that experience the greatest change in temperatures move the fastest.

The team found that on average organisms are shifting their home ranges at a rate of 17km per decade away from the equator; three times the speed previously thought.

Organisms also moved uphill by about 1m a year.

"Seeing that species are able to keep up with the warming is a very positive finding," said biologist Terry Root from Stanford University in California, US.

She added that it seemed that species were able to seek out cooler habitats as long as there was not an obstacle in their way, like a highway.

Out of range

But what about the animals that already live at the poles, or at the top of mountains?

"They die," said Dr Thomas. Take the polar bear, it does most of its hunting off the ice, and that ice is melting - this July was the lowest ever recorded Arctic ice cover - it has nowhere to go.

However, the loss of this one bear species, although eminently emblematic, seems insignificant when compared to the number of species that are threatened at the top of tropical mountains.

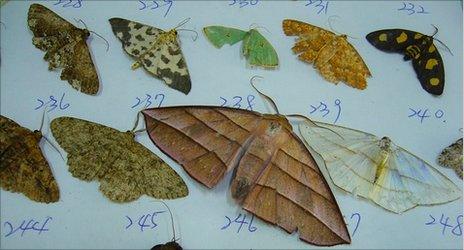

On Mount Kinabalu in Borneo, Dr Thomas' graduate student, I-Ching Chen, has been following the movement of Geometrid moths uphill as temperatures increase. Their natural ranges have shifted by 59m in 42 years.

These moths "don't have options; they are being forced up, and at some point they will run out of land," reflected Dr Thomas.

The British scientist said that it was really too early to start generalising about the characteristics of the species that had shifted their distribution to stay within their optimal temperature range.

"But we know that the species which have expanded the most and fastest are the species that are not particularly fussy about where they live," he told BBC News.

Geometrid moths are climbing Mount Kinabalu year on year