Species count put at 8.7 million

- Published

The black-capped woodnymph of Colombia was identified as recently as 2009

The natural world contains about 8.7 million species, according to a new estimate described by scientists as the most accurate ever.

But the vast majority have not been identified - and cataloguing them all could take more than 1,000 years.

The number comes from studying relationships between the branches and leaves of the "family tree of life".

The team warns in the journal PLoS Biology, external that many species will become extinct before they can be studied.

Although the number of species on the planet might seem an obvious figure to know, a way to calculate it with confidence has been elusive.

In a commentary also carried in PLoS Biology, former Royal Society president Lord (Robert) May observes: "It is a remarkable testament to humanity's narcissism that we know the number of books in the US Library of Congress on 1 February 2011 was 22,194,656, but cannot tell you - to within an order of magnitude - how many distinct species of plants and animals we share our world with."

Now, it appears, we can.

"We've been thinking about this for several years now - we've had a look at a number of different approaches, and didn't have any success," one of the research team, Derek Tittensor, told BBC News.

"So this was basically our last chance, the last thing we tried, and it seems to work."

Dr Tittensor, who is based at the UN Environment Programme's World Conservation Monitoring Centre (Unep-WCMC) and Microsoft Research in Cambridge, UK, worked on the project alongside peers from Dalhousie University in Canada and the University of Hawaii.

The vast majority of the 8.7 million are animals, with progressively smaller numbers of fungi, plants, protozoa (a group of single-celled organisms) and chromists (algae and other micro-organisms).

The figure excludes bacteria and some other types of micro-organism.

Linnaean steps

About 1.2 million species have been formally described, the vast majority from the land rather than the oceans.

The trick this team used was to look at the relationship between species and the broader groupings to which they belong.

In 1758, Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus developed a comprehensive system of taxonomy, as the field is known, which is still - with modifications - in use today.

Groups of closely related species belong to the same genus, which in turn are clustered into families, then orders, then classes, then phyla, and finally into kingdoms (such as the animal kingdom).

The higher up this hierarchical tree of life you look, the rarer new discoveries become - hardly surprising, as a discovery of a new species will be much more common than the discovery of a totally new phylum or class.

The researchers quantified the relationship between the discovery of new species and the discovery of new higher groups such as phyla and orders, and then used it to predict how many species there are likely to be.

"We discovered that, using numbers from the higher taxonomic groups, we can predict the number of species," said Dalhousie researcher Sina Adl.

"The approach accurately predicted the number of species in several well-studied groups such as mammals, fishes and birds, providing confidence in the method."

And the number came out as 8.7 million - plus or minus about a million.

Muddied waters

If this is correct, then only 14% of the world's species have yet been identified - and only 9% of those in the oceans.

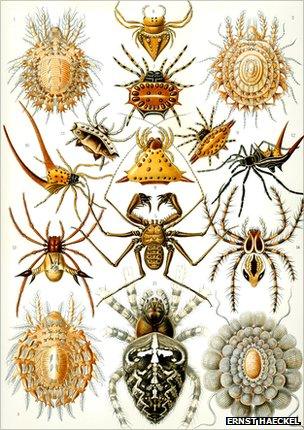

The rate of species discovery has remained about even ever since Haeckel compiled his Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature) a century ago

"The rest are primarily going to be smaller organisms, and a large proportion of them will be dwelling in places that are hard to reach or hard to sample, like the deep oceans," said Dr Tittensor.

"When we think of species we tend to think of mammals or birds, which are pretty well known.

"But when you go to a tropical rainforest, it's easy to find new insects, and when you go to the deep sea and pull up a trawl, 90% of what you get can be undiscovered species."

At current rates of discovery, completing the catalogue would take over 1,000 years - but new techniques such as DNA bar-coding could speed things up.

The scientists say they do not expect their calculations to mark the end of this line of inquiry, and are looking to peers to refine methods and conclusions.

One who has already looked through the paper is Professor Jonathan Baillie, director of conservation programmes at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL).

"I think it's definitely a creative and innovative approach, but like every other method there are potential biases and I think it's probably a conservative figure," he told BBC News.

"But it's such a high figure that it wouldn't really matter if it's out by one or two million either way.

"It is really picking up this point that we know very little about the species with which we share the planet; and we are converting the Earth's natural landscapes so quickly, with total ignorance of our impact on the life in them."

Follow Richard on Twitter, external

- Published21 August 2011

- Published9 January 2011

- Published29 April 2010