Smart UK navigation system for Mars rover

- Published

- comments

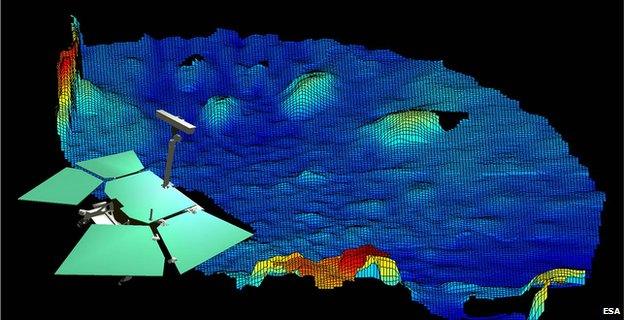

The system builds a 3D model of the terrain ahead of the rover

British engineers have developed an autonomous navigation system for a Mars rover.

The technology will guide a robotic vehicle across the surface of the Red Planet, steering it clear of hazardous rocks and gullies.

All controllers would need to do is give the vehicle the co-ordinates of a destination. The navigation system would work out the best way to get there.

It can even change the route half-way through if unexpected obstacles are encountered.

The system has been developed as part of Europe's ExoMars programme, external, the multi-million-euro project to put a rover on Earth's near neighbour in 2018.

Whether the autonomous navigation system will actually be used on that vehicle is another question, however.

Budget concerns have forced the European Space Agency (Esa) to marry its ambitions at the Red Planet with those of its US counterpart, Nasa.

Dr Jim Clemmet: "We have strong expectations that we will fly this system"

The pair are currently working on the idea of sending one large, jointly developed rover to the planet in 2018, and the responsibilities for this vehicle's many components and sub-systems have yet to be assigned.

Nonetheless, the team at Astrium UK, external believes its technology is superior to anything that's been flown to date.

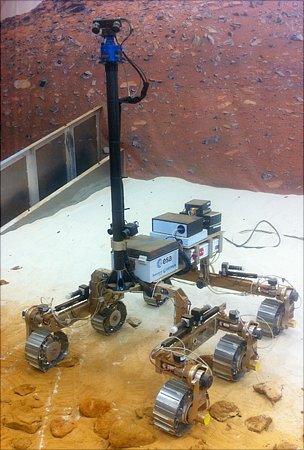

The Guidance, Navigation and Control (GNC) system has been developed at the company's Stevenage facility, using a prototype rover chassis nicknamed Bruno, external.

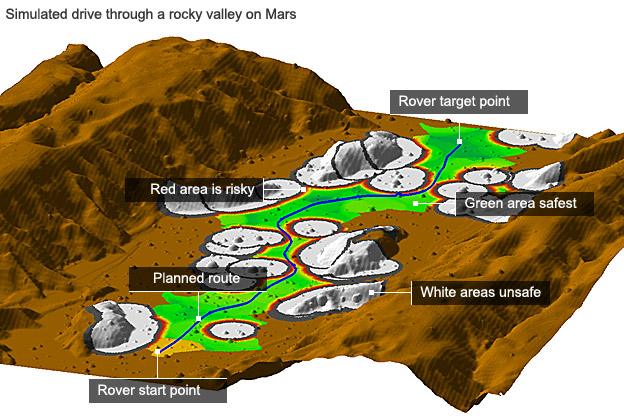

The robot runs around a simulation surface, or "Mars yard", containing sand and rocks. Bruno's GNC system employs stereo cameras on top of a mast to build a 3D model of what's ahead. Computer algorithms then analyse the terrain to plan the safest, most efficient route to the target location.

The prototype vehicles used to develop systems have had enormous outreach impact

As the vehicle sets off, another pair of stereo cameras and a suite of sensors monitor the rover's progress. The map is updated every 10 seconds.

"As each rover on Mars progresses to its next stage, obviously we try to do more and more; we're more ambitious with every mission that goes," said Dr Jim Clemmet, Astrium's ExoMars rover vehicle engineering manager.

"So, on the earlier rovers, it was great to move them around, predominantly under ground control. But, obviously, if we have more autonomy on board, we can do more science in the same timescale and hopefully also travel larger distances within the same timeframe."

If the wheels slip slightly while climbing over a rock, the new GNC system will make minor, real-time adjustments to keep the rover on the correct path. This is a significant advance over previous Mars robots. Their autonomous GNC systems have made path corrections at the end of short driving segments. The British system steers to make those corrections as the vehicle is moving.

"If you cannot correct your errors as you drive, you have to put greater margins into your chosen path to allow for the fact that you will slip off track," explained Richard Lancaster, Astrium's lead guidance and control analyst.

"By reducing those margins with this system, we can travel through more complex terrains with greater confidence - for example, rolling between two rocks and being sure we'd get through."

The UK Space Agency, external, through its membership of Esa, is now arguing strongly for the Astrium autonomous navigation system to be incorporated into the 2018 rover. Britain will be investing tens of millions of euros in the mission and it wants this capability to be one of its key contributions.

The UKSA would also like to see the prototype chassis for this vehicle undertake its testing programme in the UK.

Bruno and other "breadboards" like it have had enormous outreach impact at science shows and exhibitions up and down the country.

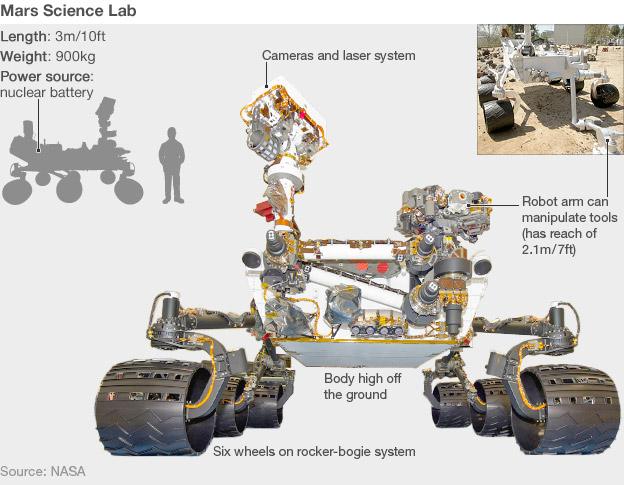

The prototype for the 2018 mission would have an even bigger wow factor. The rover is likely to be a copy - in terms of size - of Nasa's Curiosity-Mars Science Laboratory rover, external, which is due to launch in November. This robot is about the size of a Mini Cooper and weighs some 900kg.

Esa and Nasa are in the throes of making the critical decisions on the 2018 mission. Europe expects to receive a clear indication this month from the Americans that they still wish to participate in the project.

Funding woes at Nasa have put a question mark against many of its planned activities.

Already this year, the US has left Europe high and dry on several projects. In April, it walked away from three multi-billion euro missions-in-the-planning, forcing European scientists and engineers to head back to the drawing board after three years of feasibility work.

There is doubt also over the future of the James Webb Space Telescope in which Europe has a 15% share.

The 2018 rover will probably look very similar to Nasa's next rover which is due to launch in November