Alma telescope begins study of cosmic dawn

- Published

One of the 21st Century's grand scientific undertakings has begun its quest to view the "Cosmic Dawn".

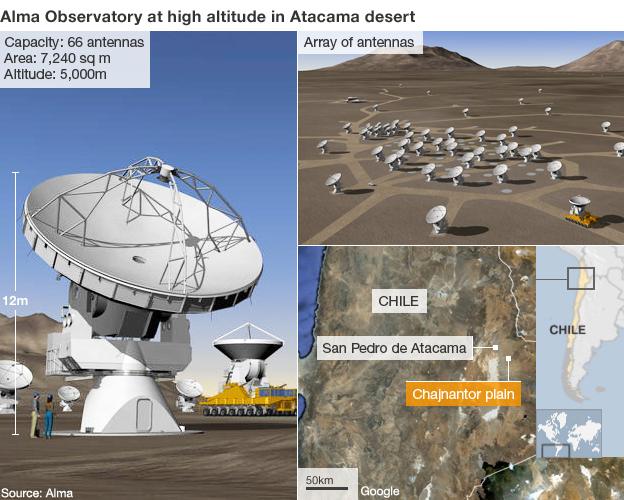

The Atacama large milllimetre/submillimetre array (Alma) in Chile is the largest, most complex telescope ever built.

Alma's purpose is to study processes occurring a few hundred million years after the formation of the Universe when the first stars began to shine.

Its work should help explain why the cosmos looks the way it does today.

One of Alma's scientific operations astronomers, Dr Diego Garcia, said that the effective switching on of the giant telescope ushered in a "new golden age of astronomy".

Pallab Ghosh looks around the array of giant antennas that makes up the telescope, on one of the highest plateaus in Chile

"We are going to be able to see the beginning of the Universe, how the first galaxies were formed. We are going to learn so much more about how the Universe works," he told BBC News.

Alma consists of an array of linked giant antennas on top of the highest plateau in the Atacama desert, close to Chile's border with Bolivia.

It has been under construction since 2003. With the addition of new antennas, the telescope has been able to see progressively deeper into the cosmos and discern star formation processes in ever greater detail.

The full testing and commissioning of its 20th antenna has enabled Alma to record events that have never been seen before. It is now that the first scientific discoveries can be made.

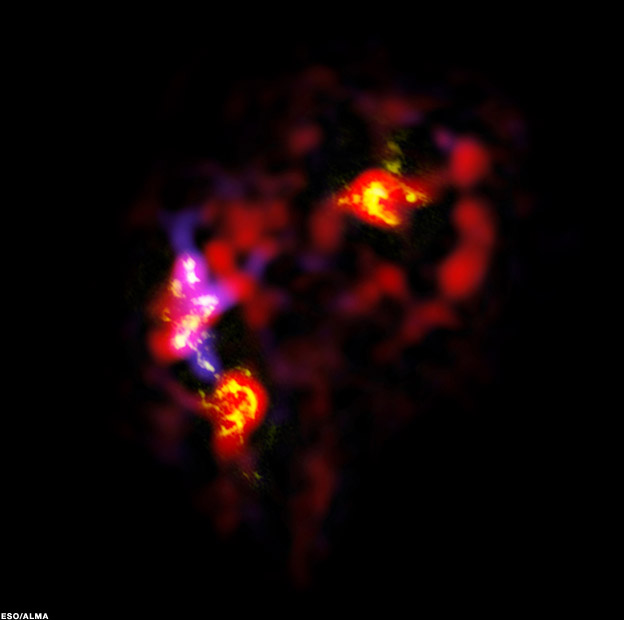

As a taster of what is to come, the European Southern Observatory, one of the organisations that run the facility, has released the first images taken by Alma. They show - perhaps appropriately for the occasion - the collision of two galaxies known as the Antennae Galaxies.

These colossal collections of stars can be seen using optical telescopes, such as the Hubble Space Telescope. But Alma, which gathers light that is not visible to the eye, is able to pick out clouds of dense cold gas from which new stars form.

The images show concentrations of the star-forming gas at the centres of each galaxy and also in the chaotic region where they are colliding. It is here that new stars and planets will be born.

The image was taken using just 12 antennas. The sharpness and resolution of images will increase dramatically as more antennas are added. The aim is for Alma to have 66 antennas by 2013.

So what do the researchers hope to discover?

Alma observes light at millimetre and sub-millimetre wavelengths. It is at these wavelengths that astronomers can make out the swirling gas that came together in the very early Universe, more than 13 billion years ago, to form the very first stars to shine in the Universe.

Cosmologists have their theories of what happened at this time. Now, astronomers will be able to literally see for themselves whether these theories are correct.

Alma will also enable them to see the formation of planets around distant stars. One of the early projects is the study of a very young star called AU Microscopii which is just 1% the age of our own Sun.

It is thought that it has a "birth ring" of matter around it that is in the process of coalescing into planets.

Astronomers are also studying processes around another young star 400-light-years away, given the functional designation HD 142527 that may be forming up to a dozen Jupiter-sized planets.

Another intriguing project is to study the supermassive black hole at the centre of our galaxy known as Sagittarius A. Dust prevents it from being seen by optical telescopes - but using Alma, astronomers will be able to see this mysterious object in unprecedented detail.

In addition, a Japanese team plans to use Alma to study another cosmic oddity: a dazzlingly bright galaxy called Himiko, creating the equivalent of 100 Suns each year, while around it little else is happening.

It is hoped that Alma can show the processes occurring deep inside Himiko's star-forming nebula.

Pallab Ghosh speaks to engineer Pascal Martinez about the technical challenges involved with the construction of Alma

But as well as being scientifically ambitious, the project is an incredible feat of engineering. The man leading the European Southern Observatory's efforts to construct the array, Pascal Martinez, described Alma as the "Pyramids of the 21st Century".

He tells me: "The sheer scale of the engineering project, its technical complexity and what this hardware will achieve in terms of our understanding is really at the cutting edge and a tribute to humanity."

Mr Martinez's job is to supervise the assembly of antennas on Alma's lower site, which is still at very high altitude - nearly 3,000m above sea level.

Each antenna is carefully put together from components shipped in from a number of high-tech companies around the globe, and then carefully transported up the plateau to the "high site" on giant 28-wheeled transport vehicles. The antennas are then placed on to their slots and connected to the rest of the array.

Alongside the European assembly site are the Japanese and North American astronomy agencies also assembling their antennas as part of their contribution to this huge international project.

Each agency, in friendly rivalry, claims that their design of antenna works best. But although the European, Japanese and North American systems each look subtley different, they do exactly the same job.

In collaboration with the Republic of Chile, each international partner has helped construct a new generation of telescope that has now begun to probe deeply into the origins of the early Universe.

- Published28 July 2011

- Published25 July 2011