Europe to lead daring Sun mission

- Published

The probe will orbit closer to the Sun than any previous spacecraft

Europe is to lead the most ambitious space mission ever undertaken to study the behaviour of the Sun.

Known as Solar Orbiter, the probe will have to operate a mere 42 million km from our star - closer than any spacecraft to date.

The mission proposal was formally adopted by European Space Agency (Esa) member states on Tuesday.

Solar Orbiter is expected to launch in 2017 and will cost close to a billion euros.

Nasa (the US space agency) will participate, providing two instruments for the probe and the rocket to send it on its way.

The Esa delegates, who were meeting in Paris, also selected a mission to investigate two of the great mysteries of modern cosmology - dark matter and dark energy.

Scientists are convinced that these phenomena dominate and shape the Universe but their nature has so far eluded any satisfactory explanation. The discovery in the late 1990s of dark energy and its influence on cosmic expansion was recognised with a Nobel Prize earlier in the day for three scientists.

Solar Orbiter was a favourite to win the Cosmic Vision contest because of its advanced development

The Euclid telescope will map the distribution of galaxies to try to get some fresh insight on these dark puzzles.

Like Solar Orbiter, Euclid's cost will be close to a billion euros. However, the mission still needs to clear some legal hurdles and formal adoption is not expected until next year. A launch could occur in 2019.

"They are both exciting missions, and it was really good to hear today that the physics Nobel Prize was awarded to research on the accelerating Universe, which is of course linked to Euclid," said Alvaro Gimenez, Esa's director of science.

"And I'm really looking forward to Solar Orbiter, which will become the reference for solar physics in the years to come," he told BBC News.

The two missions have emerged from Esa's Cosmic Vision exercise, which is planning missions up to 2025.

They were selected after four years of debate and definition involving researchers and engineers from across Europe.

The pair had to argue their case in direct competition with other compelling mission ideas, including at the final stage of selection a proposal for a planet-hunting telescope called Plato.

Esa itself will be investing about 500-600m euros in each venture, with individual member states paying for the instruments that will be carried on the spacecraft. National governments will also fund their own scientists to process and interpret the data returned by the missions.

Solar Orbiter was always regarded as something of a favourite in the race. The concept had been in development since the 1990s, and so the technologies it requires were perhaps better understood than many of its rivals.

Euclid will not only tell us about the "dark Universe", it will acquire some fabulous pictures

Its mission will certainly be challenging as it attempts to acquire measurements of the energetic particles and magnetic fields found close by our star.

The spacecraft will provide remarkable views of the Sun's polar regions and farside. Its elliptical orbit will be tuned such that it can follow the star's rotation, enabling it to observe one specific area for much longer than is currently possible.

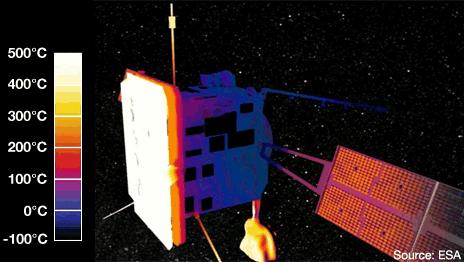

Throughout, Solar Orbiter will be staring into the "furnace". The main workings of the spacecraft will have to hide behind a shield to protect it against temperatures higher than 500 degrees; its instruments will need to peek through small slots.

"Solar Orbiter is not so much about taking high-resolution pictures of the Sun, although we'll get those; it's about getting close and joining up what happens on the Sun with what happens in space," explained Tim Horbury from Imperial College London and one of Solar Orbiter's lead scientists.

"The solar wind and coronal mass ejections - these big releases of material coming off the Sun; we don't know precisely where they're coming from, and precisely how they're generated. Solar Orbiter can help us understand that."

Tuesday's meeting of Esa's Science Policy Committee sanctioned a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Nasa for its contributions to Solar Orbiter. Delegates also approved a multilateral agreement (MLA) with the national agencies in Europe that will be providing the payload instruments.

Solar Orbiter will need to be protected by a multi-layered heatshield

Euclid will map the spread of galaxies and clusters of galaxies over 10 billion years of cosmic history.

Its optical and infrared detectors will look deep into space to see how the light from far-distant galaxies has been subtly distorted by intervening unseen, or dark, matter.

It will also map the three-dimensional distribution of galaxies. The patterns in the great voids that exist between these galaxies can be used as a kind of "yardstick" to probe the expansion of the cosmos through time - an expansion which appears to be accelerating as a consequence of some unknown property of space itself referred to by scientists as dark energy.

"Euclid will give us an insight into how structures in the Universe are growing and whether they are growing at the rate we expect from General Relativity (our theory of gravity on large scales)," said Bob Nichol, a Euclid scientist from Portsmouth University.

"But aside from all that, Euclid should also deliver a picture of the Universe that has Hubble clarity over the whole sky. Euclid will detect billions of objects and they will all be there for us to go look at. And when we look back 50 years from now, that could be the one thing about Euclid we all say was worth it - a tremendous legacy for our children," he told BBC News.

Euclid is currently a mission that Europe plans to undertake on its own.

It may not remain that way for long, however.

The Americans are desperate to run a similar mission they call WFirst (Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope). But budget pressures mean this spacecraft is unlikely to be built until after Euclid has flown, giving Europe a clear lead in one of the most important fields of modern astrophysics.

Esa has in the past offered Nasa the opportunity to take a 20% partnership in Euclid.

"The door is always open to the Americans, and we are ready to co-operate with them if they come with a reasonable proposal," said Dr Gimenez.

Co-operation with Nasa on Euclid would require another MOU.

- Published4 October 2011

- Published26 February 2011

- Published21 July 2010