Old American theory is 'speared'

- Published

It would have taken a lot of force to drive the point into the mastodon bone

An ancient bone with a projectile point lodged within it appears to up-end - once and for all - a long-held idea of how the Americas were first populated.

The rib, from a tusked beast known as a mastodon, has been dated precisely to 13,800 years ago.

This places it before the so-called Clovis hunters, who many academics had argued were the North American continent's original inhabitants.

News of the dating results is reported in Science magazine, external.

In truth, the "Clovis first" model, which holds to the idea that America's original human population swept across a land-bridge from Siberia some 13,000 years ago, has looked untenable for some time.

A succession of archaeological finds right across the United States and northern Mexico have indicated there was human activity much earlier than this - perhaps as early as 15-16,000 years ago.

The mastodon rib, however, really leaves the once cherished model with nowhere to go.

The specimen has actually been known about for more than 30 years. It is plainly from an old male animal that had been attacked with some kind of weaponry.

It was found in the late 1970s at the Manis site near Sequim, north-west of Seattle, in Washington State.

Although scientists at the time correctly identified the specimen's antiquity, adherents to the Clovis-first model questioned the dating and interpretation of the site.

To try to settle any lingering uncertainty, Prof Michael Waters of Texas A&M University and colleagues called upon a range of up-to-date analytical tools and revisited the specimen.

These investigations included new radio carbon tests using atomic accelerators.

"The beauty of atomic accelerators is that you can date very small samples and also very chemically pure samples," Prof Waters told BBC News.

"We extracted specific amino acids from the collagen in the bone and dated those, and yielded dates 13,800 years ago, plus or minus 20 years. That's very precise." It is 800 years or so before Clovis evidence is seen in the historical record.

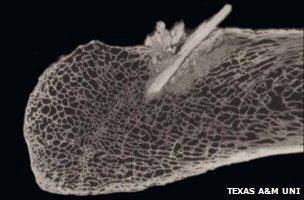

Computed tomography, which creates exquisite 3D X-ray images of objects, was used to study the embedded point. The visualisation reveals how the projectile end had been deliberately sharpened to give a needle-like quality. And it also enabled the scientists to estimate the projectile end's likely original size - at least 27cm long, they believe.

"The other thing that's really interesting is that as it went in, the very tip broke and rotated off to the side," said the Texas A&M researcher.

The CT imagery reveals the extent of the wound and the shape of the buried point's end

"That's a very common breakage pattern when any kind of projectile hits bone. You see it even in stone projectiles that are embedded in, say, bison bones."

DNA investigation also threw up a remarkable irony - the point itself was made from mastodon bone, proving that the people who fashioned it were systematically hunting or scavenging animal bones to make their tools.

The timing of humanity's presence in North America is important because it plays into the debate over why so many great beasts from the end of the last Ice Age in that quarter of the globe went extinct.

Not just mastodons, but woolly mammoths, sabre-toothed cats, giant sloths, camels, and teratorns (predatory birds with a nearly four-metre wingspan) - all disappeared in short order a little over 12,700 years ago.

A rapidly changing climate in North America is assumed to have played a key role - as is the sophisticated stone-tool weaponry used by the Clovis hunters. But the fact that there are also humans with effective bone and antler killing technologies present in North America deeper in time suggests the hunting pressure on these animals may have been even greater than previously thought.

"Humans clearly had a role in these extinctions and by the time the Clovis technology turns up at 13,000 years ago - that's the end. They finished them off," said Prof Waters.

"You know, the Clovis-first model has been dying for some time," he finished. "But there's nothing harder to change than a paradigm, than long-standing thinking. When Clovis-First was first proposed, it was a very elegant model but it's time to move on, and most of the archaeological community is doing just that."

Now extinct, the mastodon was a large elephant-like animal

- Published24 March 2011

- Published4 March 2011