UK calls for new legal climate deal by 2015

- Published

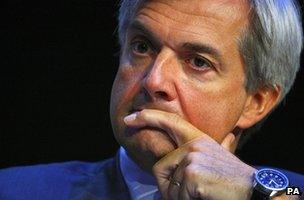

Mr Huhne used his speech to suggest time was running out to reach a new global climate deal

The UK's climate secretary has called on delegates at next week's UN climate summit to agree on a way to deliver a legally-binding global treaty by 2015.

It should "start to bite" into emissions by 2020, Chris Huhne said.

He embarked on a potential crash course with developing countries by suggesting each should pledge action appropriate to its level of development.

The developing world's overt line is to keep the firewall between "rich" and "poor" in the UN climate convention.

In a speech at London's Imperial College, Mr Huhne observed: "China is not, and will not be, the same as Chad or India.

"We need to move to a system that reflects the genuine diversity of responsibility and capacity, rather than a binary one that says you are 'developed' if you happened to be in the OECD in 1992."

Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Singapore and Kuwait all exceed the EU average per-capita GDP, while Brunei, Israel, The Bahamas and South Korea are among those not far behind.

Yet the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) puts them all in the big basket of "developing countries".

The developing world, through the powerful G77/China bloc, maintains that western countries are the only ones that must make actual cuts in their emissions because of the historical responsibility they bear.

Nations that industrialised first - such as the UK, US and Germany - have put much more CO2 into the atmosphere than others; and their primary responsibility is enshrined in the UNFCCC.

Mohammed Al-Sabban, Saudi Arabia's chief climate negotiator, put the point forcefully this week in an email to BBC News.

"Saudi Arabia, along with other developing countries, cannot accept to re-negotiate the existing UNFCCC convention - its principles, its commitments, or any of its provisions," he wrote.

"The differentiated responsibility between developed and developing countries was based on the historical responsibility of the developed countries, and has nothing to do with the new economic reality of some developing countries, as some developed countries are arguing."

Instead, he said, developed nations inside the Kyoto Protocol - all bar the US, basically - must re-negotiate future emission cuts inside the protocol's mechanisms.

A number - Canada, Japan and Russia - have made plain that they will not do that.

And Mr Huhne said that although the EU was not opposed to Mr Al-Sabban's position, the Kyoto Protocol countries only account for 15% of the world's emissions, so it would not be enough on its own to meet internationally agreed climate targets.

A technical briefing note prepared for a recent meeting of the BASIC group of countries (Brazil, South Africa, China and India) argued that climate targets could be met if the traditional "rich" bloc went into "negative" emissions - sucking more CO2 from the air than it emits - between now and 2050.

Bridging the divide

Mr Huhne's comments reflect the fact that some developing countries do privately accept that revisiting the existing definition of "rich" and "poor" would be a good idea.

In a meeting in the UK parliament last month, Xie Zhenhua, the minister in charge of China's climate policy, did not rule out the possibility that it could begin to cut its emissions soon after 2020, rather than just restrain their rise as it does now.

"China will make commitments that are appropriate for its development stage," he said.

In recent days, a number of nations - including the US and Japan - have said a new climate treaty cannot be countenanced before 2018, and probably not by 2020, putting a dampener on the fortnight-long UN negotiations that open in Durban, South Africa, on Monday.

But Mr Huhne pointed to scientific studies showing emissions should have begun to fall by that date, or shortly afterwards; which means the terms of a new treaty should be negotiated by 2015.

"We won't get that signed and sealed at Durban; but if we can at least get everybody agreed on what the objective is, that means we can then go on to do the details and get global emissions coming down well in time for 2020," he told BBC News.

"Only a comprehensive, legally-binding agreement for all can provide the clarity we need," he said.

Follow Richard on Twitter, external

- Published23 November 2011

- Published5 November 2011

- Published25 October 2011

- Published31 October 2011

- Published21 October 2011