Cayman vents are world's hottest

- Published

The world's deepest known volcanic vents are also the hottest, a UK-led expedition has indicated.

The seafloor vents are located 5km below the surface of the Caribbean, in the Cayman Trough.

The researchers say the structures are shooting jets of mineral-rich water more than a kilometre into the ocean above.

The vents' features suggest the water is warmer than 450C - hot enough to melt lead.

Nevertheless, the springs are teeming with new species including a type of pale shrimp with a light sensing organ on its back.

Details of the research have been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Researchers from the UK's National Oceanography Centre in Southampton first investigated the vents in April 2010.

The vents are known as "Black Smokers" on account of the smoky-looking hot liquids that gush out of them.

One of the vents, which the team named the Beebe Vent Field, was almost a kilometre deeper than anything previously found.

According to Dr Jon Copley, from the University of Southampton and one of the leaders of the expedition, the discovery was surprisingly moving.

"When we came across the black smokers on the sea floor there were honestly tears among the science party, there was this sort of moment of overwhelming wonder at the marvel of the world," he said.

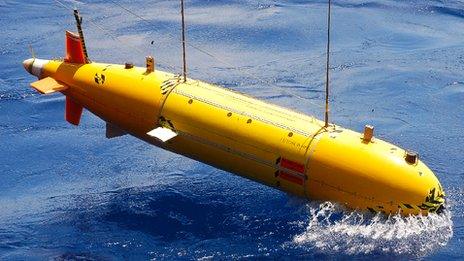

The scientists used Southampton's robot submarine Autosub6000

"The Beebe Field is a mound of mineral rubble on the bottom of the ocean estimated to be about 80m across about 50m high. On top of the mound are naturally formed chimneys, estimated to be about six metres tall with hot fluid gushing out."

The scientists say the fluid is rich in minerals, particularly copper.

"As soon as it hits the cold sea water, it starts to form particles of copper that build up the chimneys we've seen," Dr Copley explained.

The researchers weren't able to directly measure the temperature of the water with their equipment.

"We analysed the chemistry of what was gushing from the vents and from that we estimated that these vents could be hotter than 450 degrees Celsius, which means they're not only the deepest known they're also possibly going to be the hottest known."

The height of the plume is also indicative of extremely high temperatures.

Mountain vents

Of perhaps greater scientific interest is another, shallower vent field that the team discovered on the side of an undersea mountain called Mount Dent.

Normally vents occur where you get volcanic activity on the ocean floor. But the black smokers on Mount Dent were some distance from a volcanic zone and Dr Copley believes this could be a clue that vents occur in far greater numbers than previously thought.

"The kind of underwater area where we found the second set of vents, we think is actually quite common around the world's oceans and so if you can get vents on mountains like that it could be that there are a lot of them out there dotted around."

The vents are also known as "black smokers"

This view is shared by Dr Nicole Dubilier from the Max Planck Institute of Marine Microbiology, who has also explored deep sea vents.

"I am convinced that deep sea vents are very common and this is only the beginning of a hopefully long line of future discoveries," she said.

"That we now have the technology to explore and sample such exotic environments is exciting in itself, comparable to the fact that we can collect rocks from the moon or may one day be able to collect them from Mars."

Dr Timothy Shank from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, who was part of the team that discovered the first known vent communities around Antarctica, said: "The fact that these deep vents have species observed no where else, is just like the fact that there are different suites of land species that have evolved on different continents—much the way kangaroos have evolved only in Australia and giraffes only in Africa.

"What is key now is to see if the chemicals in the hydrothermal vent fluids differ from those known throughout the world. Differences in fluid chemistry in these deep vent systems may have dictated adaptations to the environment"

The team in the Cayman Trough also found details of new species including an eyeless, pale shrimp with a light-sensing organ on its back which Dr Jon Copley believe may help them to find their way round the murky depths.

"It may use the organ to help navigate in the very faint glow you get from deep sea vents, the glow is too faint for us to see with our eyes and our cameras, but the glow is there and we think the shrimps are using it to navigate around the vents," he said.

The scientists say the closest known relatives of this shrimp are found 4,000km away in the middle of the Atlantic. Understanding how these species evolve and move is crucial, says Jon Copley, to being able to manage the vents should commercial exploitation of the minerals they contain ever be contemplated.

"Last year China was granted one of the first licences for exploratory mining along a section of undersea volcanoes in the Indian Ocean, so we are starting to see interest in chasing these resources," he explained.

All the more reason we need to understand their patterns of life if we are going to make responsible decisions about how to manage these resources."

- Published16 December 2010