UK space sector 'on the up'

- Published

- comments

The £10m Kepler facility is owned by the University of Surrey and leased to SSTL

If you want to get a sense of how good the British space sector feels about itself right now, take a look at the shiny new building that's just gone up on the Surrey Research Park, external.

The Kepler facility, external is a major new centre for the production and testing of satellites. It's where the first big batch of operational spacecraft for Europe's Galileo sat-nav project, external is being assembled - a total of 14 satellites.

There are other platforms in various states of readiness - for Kazakhstan, for Canada, Russia, China and the UK.

The building represents must-have capacity for Surrey Satellite Technology Limited (SSTL) which has now outgrown the cleanroom area - workspace with a controlled environment to minimise contamination - on its existing site in Guildford.

Leaving aside the UK's investment in Galileo, key upcoming British projects to be put together in the Kepler facility include a novel radar satellite called NovaSAR, and a spacecraft to demonstrate the smartest new ideas in space technology, appropriately called TechDemoSat.

The latter is farther along in its build and, although it might not look like it right now, should be ready for launch this year.

Kepler was officially opened by European Space Agency (Esa) Director General Jean-Jacques Dordain, alongside Universities and Science Minister David Willetts.

The minister has been banging the drum for space ever since he came to office. The coalition government considers the sector to be a "winner" - one that can help put "UK plc" back on track.

Inside the SSTL cleanroom - hi-tech manufacturing is one path to re-balance the British economy

Space has been one of the few areas of the economy to experience continued growth, even through the recession, and the Kepler building is a clear symbol of that upward trajectory.

As I've written before, government and industry now have a joint plan to push the sector forward, and Mr Willetts has been steadily ticking off the boxes in a checklist that broadly follows the recommendations in the Space Innovation and Growth Strategy (S-IGS), external published in 2010.

This document laid out the path it believed could take the UK from a position where it currently claims about 6% of the world market in space products and services to about 10%, by 2030, creating perhaps 100,000 new hi-tech jobs in the process.

Key S-IGS recommendations implemented so far include the establishment of the UK Space Agency (UKSA), external.

Government support for NovaSAR and TechDemoSat are ticks in the boxes that called for investment in Earth observation and R&D.

Other ticks go next to the International Space Innovation Centre (Isic) set up at Harwell, Oxfordshire, and the Catapult Centre in Space Applications at a yet-to-be decided location, although quite possibly alongside Isic. These institutions are very much industry-focused and will seek to foster near and far ideas and bring them to market.

"The story of Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd for me is an absolute model," said Mr Willetts.

"It began in the labs of Surrey University and then became a full-blown space business.

"It has grown and grown, and now has hundreds of people working for it. So this is an example of how successful businesses can be spun out of university research, and it's now become a key part of the British space sector.

"I hope as you look back over the first 18 months of the coalition that you will see that we are absolutely committed to the space sector as one of the key sectors that can re-balance the economy, as we escape from dependence on financial services, and as we remind ourselves of our strengths in science and innovation."

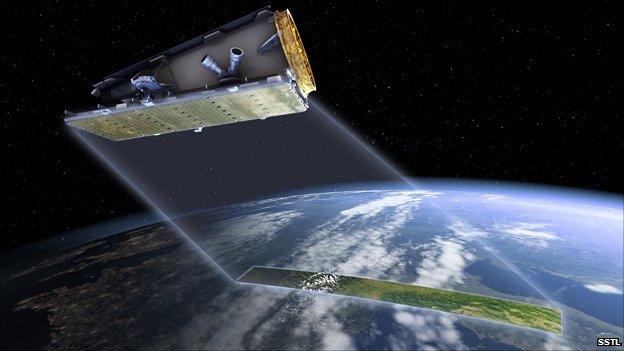

Public money is helping put the NovaSAR satellite in orbit so it can demonstrate its capabilities

There is, however, a big box looming that many people are now wondering how the minister will tick, and this is the S-IGS recommendation that government substantially increase its subscription to the European Space Agency.

At present, the UK is the fourth largest contributor (260m euros/£215m in 2012) behind Italy (350m euros), France (717m euros) and Germany (750m euros).

All 19 member states of Esa will meet in November to agree programmes and budgets for the next three to five years. The last round in 2008 was valued at some 10bn euros, external, but at that stage the economic situation was nothing like as bad as it is now, and the euro crisis had yet to show itself.

Nonetheless, Mr Dordain expects to put a bold programme before the Esa family at the end of the year that he hopes will invigorate the hi-tech sector across Europe.

"I am shooting for more," he told me. "Obviously, it's the member states' decision but we have so many good ideas that I shall make ambitious proposals at the ministerial meeting.

"But, as I keep saying, I don't live on a different planet - I understand the economic situation, and that's why I am taking actions to make Esa more efficient. However, the current situation is not a reason to be pessimistic about the future."

It is of course in the nature of the space industry that one of the biggest customers for its products is government.

Look at the satellites in preparation in the new Kepler facility and many of them are heavily dependent on tax-payer money. Galileo is the classic example - a European Commission project being procured on its behalf by Esa. So, money invested in Esa is money that will come back to the UK in the form of contracts for companies like SSTL.

Colin Paynter is the UK chief executive officer for Astrium UK, which like SSTL is a subsidary of EADS Astrium, external. He's hopeful the UK will arrive at a meaningful settlement on its Esa subscription after looking at individual business cases in Earth observation, remote sensing, communications and so on.

"I think we have some good business cases," he said. "So, I'm fairly optimistic that the government will come forward with a reasonable financial package at the Esa ministerial.

"We would certainly hope the government would take the long-term view because these are commitments that will be cashed out over a long period of time, and we all hope that the economy recovers over that period."