Seeing more clearly in infrared

- Published

- comments

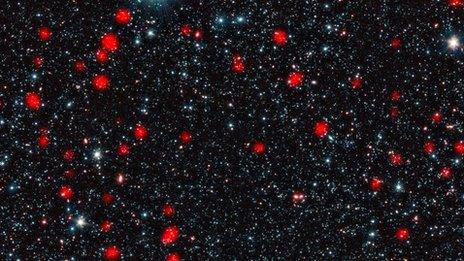

Stills from the broad panorama of the Carnia Nebula

Another stunning set of images of the cosmos - this time of the Carina Nebula - from the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope.

At 7,500 light-years from earth - deep in the heart of the southern Milky Way - this cloud of glowing gas and dust is one of the closest stellar nurseries to earth. An incubator that includes some of the heaviest and brightest stars in the night sky.

But what's really interesting about this series of images is the insight it gives into the way astronomers use infrared light to penetrate the foggy veil of particles obscuring the view.

This handy time-lapse video switches from visible to infrared wavelengths as it zooms in on interesting features around the Carina Nebula.

It shows not only the brilliant massive stars and brightly lit clouds of dust visible to conventional optical telescopes, but also the hundreds of thousands of other, much fainter and more distant, stars that are normally hidden from view.

The impenetrable glowing fog is created by the light absorbing and scattering properties of gas and dust particles. But because infrared light operates at longer wavelengths its signal passes through the clouds relatively unscathed.

The team, led by Thomas Preibisch from the University Obversatory in Munich, used the VLT's HAWK-1 infrared camera to generate hundreds of individual images that have been combined to create the footage.

Towards the bottom left is the mysterious and highly unstable star Eta Carinae - the second brightest star in the night sky for several years in the 1840's, and destined to explode as a supernova in the near future. The bright star cluster close to the centre of the picture is Trumpler 14 with even more stars in the cluster visible in the infrared view, while the small concentration of yellow stars over on the left-hand side have been revealed for the first time.

Clearly there's more to infrared astronomy than meets the eye.

- Published8 February 2012

- Published3 February 2012

- Published25 January 2012

- Published11 January 2012