'New frontier' of Antarctic lake exploration

- Published

Vostok station is one of the most difficult places to work on Earth

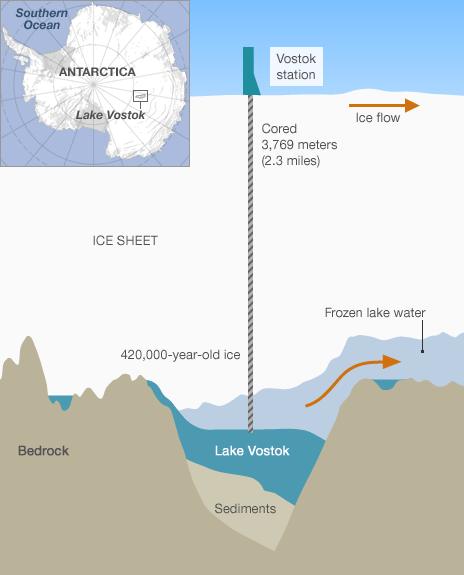

When a Russian drilling team reached Antarctica's Lake Vostok last week, they were able to claim a world first.

No one had previously penetrated one of the continent's sub-glacial lakes, prompting Valery Lukin from the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute (AARI) in St Petersburg to liken his team's achievement to the Moon landings in 1969.

Whatever the comparison, it represents a remarkable feat.

Over 20 years of stop-start drilling, the Russian team ground their way through 3.7km (2.3mi) of solid ice, working in one of the most inhospitable environments on Earth.

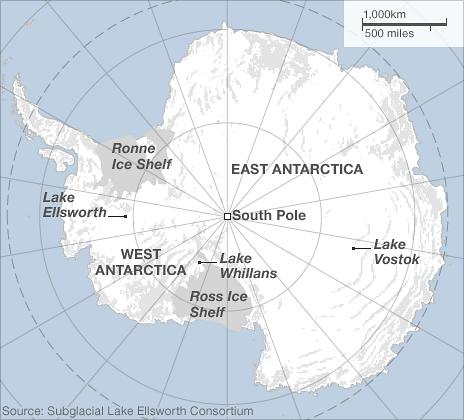

The Vostok project is one of several similar ventures being undertaken in the world's last wilderness. In West Antarctica, the British Antarctic Survey (Bas) is hoping to begin its effort to drill into Lake Ellsworth, external, while the American Wissard, external project is targeting Lake Whillans.

More than 350 sub-glacial lakes - kept in liquid form by pressure from above and the Earth's heat below - have now been identified across Antarctica, and many others may lie undetected.

Together, they form a huge and only partially connected network. Some that may have remained completely isolated could host life forms new to science: cold-loving micro-organisms that have been left to their own evolutionary devices for millennia.

"We've got this vast continent, but we've never really sampled the terra firma," said Montana State University's John Priscu, lead investigator on the US project.

Conditions in Antarctic lakes may not be so different to those on icy moons such as Europa

He said the "new frontier" beneath the ice sheet could hold an entire ecosystem of microbial life. "There's lots of melt under there... I have called it the planet's largest wetland."

The projects are of particular fascination to astrobiologists, who study the origins and likely distribution of life across the Universe.

Conditions in these Antarctic lakes may not be so different from those in liquid water bodies thought to exist under the surfaces of icy moons in the outer Solar System such as Jupiter's Europa or Saturn's Enceladus.

But just how isolated each lake has been will affect the prospects for finding any novel life.

The water within the lake at Vostok is expected to be younger than the lake's age of 14 million years; despite the lake's isolation, water can still get in and out.

A process of melting and freezing at its uppermost regions recycles the water every 10,000-15,000 years.

But it is about 800m to the bottom of Vostok, and Prof Priscu said the water there is probably stagnant and could be millions of years old.

By contrast, Lake Ellsworth is steep-sided, and much smaller - roughly the size of England's Lake Windermere.

Because of its reduced volume, water here is recycled on hundred-year timescales.

America's target, Lake Whillans averages just 10m-15m in depth. Satellite data suggest the lake water is flushed out on a cycle of just three to 10 years.

Faster method

Just how the frontier is being explored will affect what is found as the three teams aim to retrieve water and sediments from the lakes.

At Vostok, the team is using techniques familiar from the process of gathering cylindrical samples called ice cores, punching through the ice and using kerosene as an "anti-freeze".

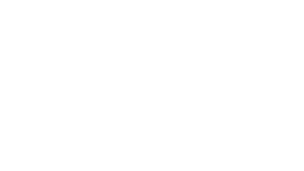

The Ellsworth and Whillans programmes will use a drill of pressurised water at 90C to melt through the ice at a rate of 50-100cm per minute - much faster than coring.

Some scientists are worried about the potential for the Vostok team's approach to contaminate both the lake and any samples brought up for analysis.

Ice cores retrieved during the drilling are analysed at the research station in Vostok

Prof Martin Siegert, from Edinburgh University, heads up the Lake Ellsworth project. He told BBC News that ice-coring "doesn't really work as a viable technique to do long-term, clean access and exploration of sub-glacial lake environments - because of the issues with cleanliness and sterility".

He said studies of microbes in ice above Lake Vostok remained "contentious" because of the issue over kerosene - of which the Vostok cores are said to "reek".

Prof Siegert defended the cleanliness of the planned Ellsworth operation, but pointed out that hot water drilling had a downside: "Once the hole is created, it contains water, not anti-freeze. So it will start to freeze up immediately.

"But that's not bad, because once you're finished it's like you were never there; your footprint on the environment is low."

Vostok expedition leader Valery Lukin has his own concerns about the hot water technique.

"Imagine the ancient water of Lake Ellsworth: it is absolutely untouched," he told Reuters.

"Maybe there is life there and a pot of boiling water is poured in. Do we want to study micro-biodiversity or microbe soup?"

Martin Siegert points out that the water in the drill head will only be a few degrees above 0C as it enters the lake - it inevitably cools as it flows 3km down into a hole that is surrounded by ice at -35C.

Nikolai Vasilyev, who led the team from the St Petersburg Mining University for the Vostok breakthrough last week, insisted that "absolutely nothing fell into the lake".

The team said it used a small drill to penetrate the last metres of ice and immediately withdrew it, allowing the lake water to percolate up and create a frozen plug that the team will collect next year.

Regardless of method, it is possible that none of the teams will find isolated, novel life in the icy depths.

The Ellsworth hot water drill comprises a spraying device on the end of a 3.2km-long hose

"One of the things people have thought about is whether some lakes are sterile, because of all the atmospheric gases that dissolve from the ice into the water," said Hamish Pritchard, a researcher at Bas.

"Atmospheric gases are trapped in bubbles and when the ice melts into the lake, the gas gets released into the water, saturating it. This would make the water quite toxic, with very concentrated oxygen and nitrogen levels."

Prof Priscu said that getting to the literal bottom of the questions could take years - but that there were many options.

"In the next few years... I would envisage an international project, picking a site somewhere in Antarctica. We could form a science consortium to go maybe back to Vostok, go to the deepest part of that lake, instead of the edge where the Russians are," he said.

"Or we could go to Concordia - a big lake by Vostok. There are lots of them to choose from."

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk

- Published8 February 2012

- Published16 January 2012

- Published5 December 2011

- Published11 October 2011

- Published28 January 2011

- Published28 January 2011