Antarctic's hidden world revealed

- Published

Ever wondered what Antarctica would look like without all that ice?

Scientists have produced the most detailed map yet of the White Continent's underbelly - its rock bed.

Called simply BEDMAP, this startling view of the landscape beneath the ice incorporates decades of survey data acquired by planes, satellites, ships and even people on dog-drawn sleds.

It is remarkable to think that less than 1% of this rock base projects above the continent's frozen veil.

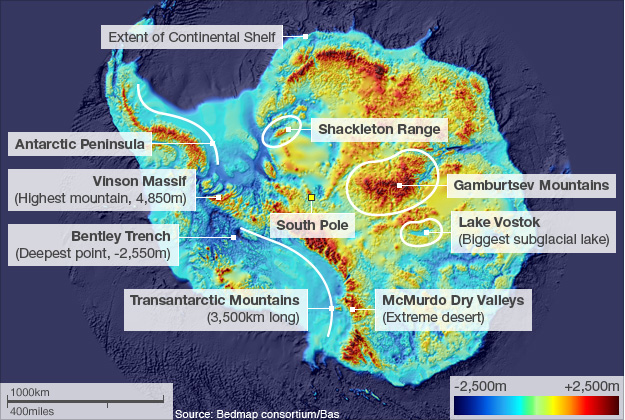

In the map at the top of this page, the highest elevations are marked in red/black. The light blue colour shows the extent of the continental shelf.

The lowest elevations are dark blue. You will note the deep troughs within the interior of the continent that are far below today's sea level.

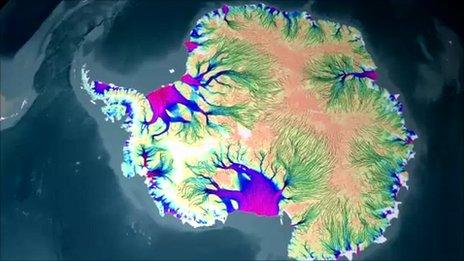

An animated view of Antarctica, revealing its great mountains and deepest depressions

The map is a fascinating perspective but it is more than just a pretty picture - it represents critical knowledge in the quest to understand how Antarctica might respond to a warming world.

Scientists are currently reporting significant changes at the margins of the continent, with increasing volumes of ice now being lost to the ocean, raising global sea levels. The type of information contained in BEDMAP will help researchers forecast the pace of future events.

"This is information that underpins the models we now use to work out how the ice flows across the continent," explained Hamish Pritchard from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"The Antarctic ice sheet is constantly supplied by falling snow, and the ice flows down to the coast where great bergs calve into the ocean or it melts. It's a big, slow-speed hydrological cycle.

"To model that process requires knowledge of some complex ice physics but also of the bed topography over which the ice is flowing - and that's BEDMAP."

Dr Pritchard is presenting the new imagery on Monday to the 2011 American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, the world's largest annual gathering of Earth and planetary scientists.

This is actually the second generation of the digital BEDMAP. The first version, which was produced in 2001, incorporated 1.9 million measurement points. For BEDMAP2, the sampling has been raised to more than 27 million points on a grid spacing of 5km.

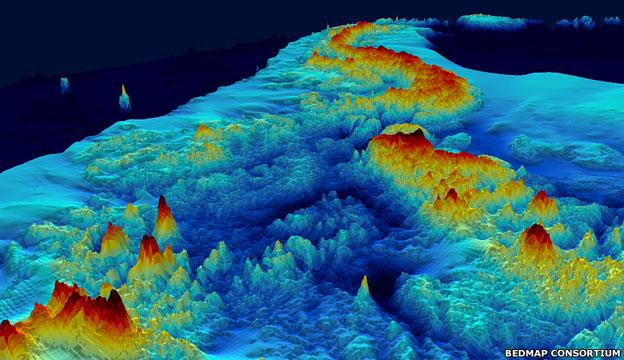

"It's like you've brought the whole thing now into sharp focus," Dr Pritchard told BBC News.

"In many areas, you can now see the troughs, valleys and mountains as if you were looking at a part of the Earth we're much more used to seeing, exposed to the air."

The source data comes from a range of international partners. Dr Pritchard and BAS colleagues Peter Fretwell and David Vaughan have merged it all into a single product.

Instrumented planes fly grids across the surface of the ice to survey what lies beneath

The project has benefited greatly from the large number of airborne radar surveys that have been flown in recent years.

Unlike rock, ice is transparent to radar. So by firing microwave pulses through the overlying sheet and recording the return echoes, scientists can plot both the depth of the rock bed and - by definition - the thickness of the ice covering.

Instrumented planes, guided by GPS, will now fly back and forth across the ice in campaigns that can last weeks at a time.

Hamish Pritchard: Some areas of Antarctica still lack good data

Perhaps the most publicised of these recent efforts was the multinational expedition in 2007/2008 to map the Gamburtsev mountains.

This range is the size of the European Alps with the tallest peaks reaching 3,000m above sea-level - and yet they are still hidden below more than a 1,000m of ice.

"It's fascinating to see the Gamburtsevs in the context of the other big mountains in Antarctica," said Dr Pritchard.

"They're similar in size to the likes of the Ellsworth and the Transantarctic mountains, but of course they're completely buried. It is just because the ice is so thick in the middle of the ice sheet that they're not exposed."

It is clear from BEDMAP2 that there are still two big areas of the continent that need improved coverage.

One of these lies between the Gamburtsevs and the coast; the other runs south of the Shackleton mountain range towards the South Pole.

Look closely at the map on this page and you can see that the yellow colouring in these areas appears quite smudged.

It is very likely that proposals will soon be put to national funding agencies to go and close these data gaps with airborne surveys.

Some of the data that is of highest value to glaciologists covers the deep troughs under West Antarctica

- Published19 August 2011

- Published3 March 2011