Where now for Mars exploration?

- Published

- comments

Bolden wants Mars robotic exploration to fit better with human exploration goals

It's the planetary scientists who probably have the glummest faces a day after President Obama announced his 2013 budget request for Nasa.

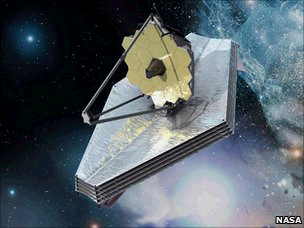

Although the agency gets a flat budget overall ($17.7bn), external, there are ongoing and expensive commitments in certain portions of the financial pie - such as to the SLS "monster rocket" and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) - and this puts a squeeze on other areas.

Planetary science loses 20% of its current $1.5bn budget, with Mars exploration taking the single biggest hit, down from $587m this year to $360m next year - a 39% reduction.

The chief casualty, as I predicted last week, is the Americans' joint missions to the Red Planet with Europe in 2016 and 2018.

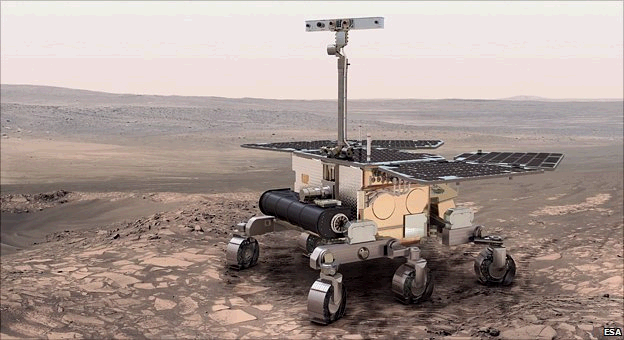

ExoMars, as we call it on this side of the pond, envisages a satellite to study the Martian atmosphere, followed by a large robotic rover to drill beneath the surface and cache rocks for later return to Earth. The Americans have severed their involvement.

It means that in the space of 12 months, Nasa has now pulled the plug on five major missions it was planning with Europe:

Lisa gravitational wave observatory

International X-Ray Observatory

Europa-Jupiter System Mission

and now ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter in 2016

and ExoMars rover in 2018

If you include the uncertainty from the summer campaign by some politicians on Capitol Hill to have the JWST terminated - a project that represents a half-billion-euro investment for Europe - you will forgive many Europeans for thinking that the US is a pretty unreliable partner right now.

Nasa administrator Charles Bolden said it was problematic to take part in the ExoMars project because it was billed as a "flagship mission".

"It was another multi-billion-dollar mission," he explained when he revealed details of the 2013 budget request.

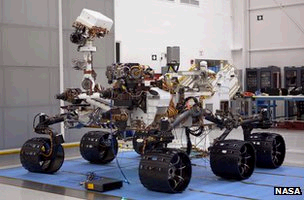

"We have Mars Science Laboratory [the Curiosity rover] on its way - a flagship. We have James Webb Space Telescope in work - a flagship.

"Flagships are essential for this nation. Anybody in the scientific community will tell you that anybody who wants to lead the world in scientific exploration and discovery has to do flagships every once in a while. We just could not do another flagship right now. It was not in the cards with the budget, given these very difficult fiscal times."

European member states have invested more than 200 million euros in ExoMars thus far

ExoMars is now in intensive care. The European Space Agency (Esa) is talking to the Russians about the prospect of them picking up many of the responsibilities on the two missions dropped by Nasa.

They're understood to be very keen. But it's not a perfect substitution and there will inevitably be additional costs that would break what Esa member states have said is a cap on expenditure for ExoMars - a billion euros and not one cent more.

A number of countries, the UK included, have restated that position in the past few days.

The next few weeks will be critical, as Esa officials try to pull together a technical, political and financial consensus to move forward.

If they cannot achieve that consensus, then an Esa council meeting in March will probably be the moment that ExoMars finally flat-lines.

The $8.8bn projected total cost of JWST puts a big squeeze on other activities

It's hard to imagine this uncertainty can be allowed to drag on. And a further delay (there have been plenty already) in the launch schedule of the missions would simply not be tolerated, and would only add to the overall cost.

If it does all unravel, what might emerge from the wreckage?

Charles Bolden and his new science chief, "Hubble repairman" John Grunsfeld, external, think they have a workable scenario.

They want future efforts at the Red Planet to be a better fit with human spaceflight ambitions. That is, future robotic ventures at Mars must do stuff which feeds into an eventual manned mission that Barack Obama has said should be a goal for the 2030s.

To that end, preliminary discussions have started on a Nasa-led Mars mission in 2018 that would probably cost $1bn rather than the $1.5bn Nasa had anticipated spending on ExoMars.

Science chief Grunsfeld would get money from the human spaceflight and space technology directorates to help pay for it.

He refuses to be specific about what this mission might entail, but asks us to look at the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter that was sent to the Moon to retrieve information helpful to future astronaut ventures.

The Mars Science Laboratory (Curiosity rover) could be the last surface mission for a while

From this, I read tasks such as landing site selection and identifying resources on the planet's surface that could be used by human explorers.

Grunsfeld told reporters: "If you ask any planetary scientist, 'what would you like to do at Mars?', they give you their list. And then say, 'what if you could go yourself to Mars; what would you do, how would you do it?', and they come up with another list.

"And then you look at the overlap of that list, and you find out, in fact, that it is mostly overlapped.

"When we send geologists, planetary scientists, astrobiologists to Mars, they're going to want to do the same kinds of things that one would want to do by sending robotic spacecraft. It's just a question of 'what can we do and when can we do it?'."

Europe has already been asked if it would be interested in participating in this effort. Early discussions were said by Grunsfeld to have gone "very well". But this is no ExoMars, and it would represent scant return for the more than 200m euros already invested by Esa member states in that project.

I doubt very much whether Esa delegations would buy into such a venture - not after what has just happened in the past 24 hours.

I sense some big arguments - and a fair amount of recrimination - could be about to follow.