Herschel telescope 'in last year'

- Published

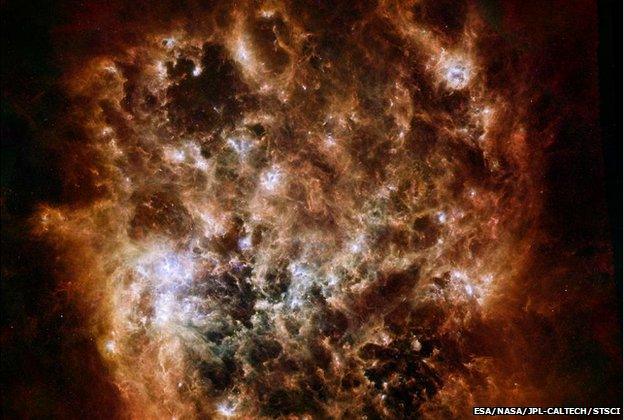

Herschel views the Large Magellanic Cloud (the image incorporates data from Nasa's Spitzer telescope)

Herschel, Europe's billion-euro space observatory, has entered what is likely to be its last year of operation.

The telescope studies the formation of stars, and has taken some remarkable pictures since its launch in May 2009.

But its detectors require a constant supply of superfluid helium to keep working, and the store of this coolant has now dropped to less than 100kg.

This past week saw Herschel begin what engineers believe will be the final 365 days of its mission life.

"There's quite a bit of uncertainty in all this, of course," said Dr Paul Goldsmith from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, US.

"It could be 11 months, it could be 14 months, and we're naturally hoping for the latter. It's certainly true that we have enough observations proposed to go well past the year if the helium lasts that long," he told BBC News.

Margaret Meixner: Great observatories... make huge data archives that live on for decades

Dr Goldsmith has been discussing the observatory's successes during a special seminar here in Vancouver at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

He is the US space agency (Nasa) project scientist on the mission. Although principally a European Space Agency (Esa) venture, Herschel has a 6% contribution from the Americans, who provided some mission-enabling technology for two of the telescope's three instruments.

But in what is an indication of just how well the US has been able to leverage that 6%, it is likely that about a half of the remaining opportunity observations on Herschel will be led by astronomers from American institutions.

"Herschel has been so open," said Margaret Meixner, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

"There's been no counting of how much time Europe has had or how much America and Canada have had - it's been about whatever the best science is. I don't think there's ever been a space telescope quite like that."

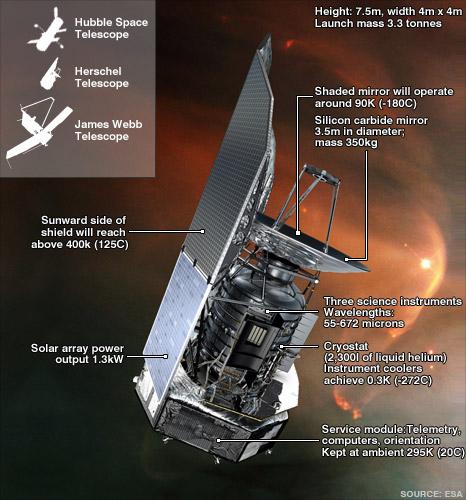

The Herschel telescope has to be kept extremely cold to study its frigid targets

Herschel was launched in May 2009 and sent to an observing position 1.5 million km from Earth.

Its goal has been to study the processes at play in the formation of stars and the evolution of galaxies. Its detectors pick up the light coming from the frigid clouds of gas and dust that are being warmed by the brilliant newborn stars buried within them.

This is long wavelength light, beyond the detection of our eyes or a telescope like Hubble. It is in the far-infrared.

To pick it up, parts of Herschel's instruments have to be cooled to near absolute zero (-273.15C), and this has been made possible by a store of superchilled helium. The telescope was launched with more than 2,000 litres, and this has been gradually boiling off as operations have progressed.

When it is all gone, the temperature of the instruments and their detectors will rise and the telescope will go blind.

The minimum expectation had been for 3.5 years of observations. The amount of helium still left in Herschel's tank, or cryostat, means this objective should be surpassed easily.

Dr Meixner said Herschel's legacy would be long-lived.

"The thing about the great observatories is that they make huge data archives that live on for decades.

"Herschel, because of its exquisite sensitivity, really is going to be a pathfinder for future projects in this area for at least 30-plus years.

"Facilities just coming online like [the radio telescope] Alma have very small fields of view - people need to know where to point, and they are going to run to the Herschel archive and say 'where do I look?'. It's how they will do their source selection."

Dr Meixner showed the meeting an image she has just acquired using Herschel. It is a view of the Large Magallenic Cloud, a small satellite galaxy to our own Milky Way.

"It's my latest pride and joy," she told BBC News.

"It looks like a fiery image, but what you're seeing there is all the dust emission from that galaxy. It's very knotty and filamentous - it's sort of like the chaos of creation. Those filaments and stuff are where the stars are going to form in that galaxy."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published17 January 2012

- Published13 January 2012