Super-cool Planck mission begins to warm

- Published

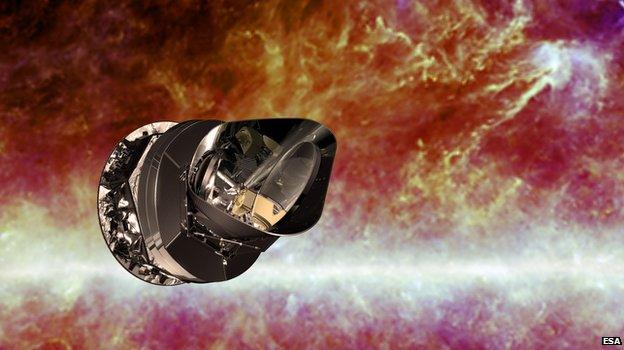

Planck was put in space in 2009: It has gathered far more data than anyone dared hope

One of Europe's great astronomical ventures is coming to a close.

The Planck telescope, put in space to map the oldest light in the Universe, has run out of the helium coolant that keeps it in full working order.

Engineers expect, external the observatory's systems to start to warm from their ultra-frigid state in the coming days, blinding one of its two instruments.

Nonetheless, Planck has gathered more than enough data since its launch in 2009 to complete its mission goals.

"We have had a flood of data - much more data than originally anticipated, and now we are in the frantic phase," revealed Jan Tauber, the European Space Agency's (Esa) Planck project scientist.

"In a year's time we have promised to deliver our maps and scientific papers, so we are feeling some pressure," he told BBC News.

Planck's quest has been to survey the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) - the "first light" to sweep out across space once a post-Big-Bang Universe had cooled sufficiently to permit the formation of hydrogen atoms.

Before that time, scientists say, the cosmos would have been so hot that matter and radiation would have been "coupled" - the Universe would have been opaque.

The CMB pervades the entire sky, and scientists can measure tiny temperature variations in it to glean information about the age, contents and shape of the cosmos.

Two American satellites have already done this, but Planck is much more sensitive and can make much more detailed maps, with higher resolution.

To do this, some of its light detectors have had to operate at the astonishingly low temperature of minus 273.05C - just a tenth of a degree above "absolute zero", the lowest temperature theoretically possible in the Universe.

A layered system of coolers was used to get down to this temperature, exploiting an unusual effect of mixing two isotopes of helium (helium-3 and helium-4) to achieve the deepest chill.

But Planck's store of the helium-3 refrigerant has now run dry and engineers have informed Planck's science team that they will soon lose the use of the observatory's High Frequency Instrument (HFI).

Without it, the CMB cannot be seen across all its frequency range.

This is expected to happen as soon as the weekend. A more formal statement on the status of Planck will then be released by Esa. This may come on Monday.

"We always knew we would eventually lose HFI and the helium has run down exactly when we thought it would - on the dot," explained Dr Tauber.

Planck still has use of its Low Frequency Instrument, which can operate at slightly higher temperatures (-269.15C), and this will continue gathering data for another six to nine months.

This information will be used to further refine the CMB maps, the first of which should be made public in January 2013.

The mission has far exceeded its minimum requirements. These called for the CMB to be scanned across the full sky at least twice.

Thanks to uninterrupted science operations since the August of 2009, Planck has now acquired five scans of the full sky.

"I think we lost just one day," Dr Tauber said. "Planck has been perfect; we've never had a serious issue with the satellite or the instruments."

The larger scientific community is eagerly awaiting Planck's CMB analysis.

Some of Planck's detectors were probably the coldest surfaces anywhere in space

Past pioneers in the study of the Cosmic Microwave Background have earned a clutch of Nobel Prizes, and there is great optimism that the super-sensitivity of Planck will advance the field considerably.

One hope is that Planck could find firm evidence of "inflation", the faster-than-light expansion that cosmologists believe the Universe experienced in its first, fleeting moments.

Theory predicts this event ought to have left its imprint on the way the ancient light is polarised. Establishing the presence of this signature, though, will be painstaking work and no definitive statements are likely to come from the Planck team on this issue before 2014.

"It's a bittersweet moment; the prime phase of Planck's observing will very soon be over, which is of course sad," said Prof Mark McCaughrean, head of Esa's Research & Scientific Support Department.

"But we have far more data in the bag than expected and it's excellent stuff. People analysing it are really excited about what we're going to learn about the early Universe, soon after the Big Bang."

What Planck sees: To get a clear view of the CMB (magenta/yellow), scientists need to filter out the signal from all the gas and dust in our galaxy (blue/white) that shines at the same frequencies. Once this "noise" is removed from the sky maps, researchers can start to probe the information they contain

Planck was launched on the same rocket as Esa's other flagship space telescope, Herschel, on 14 May 2009.

Both were despatched to an observing position 1.5 million km from Earth.

Herschel views the cosmos at infrared wavelengths to study processes that drive star formation.

Its instruments also need to operate at ultra-low temperatures, and just like Planck uses liquid helium to achieve them. However, its larger refrigerant store has roughly another year of supply.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published3 August 2011

- Published11 January 2011