Q&A: Solar storms

- Published

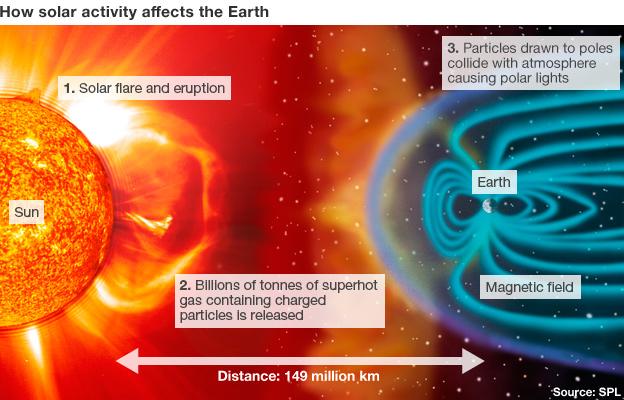

Polar lights are one manifestation of activity in the Earth's magnetosphere

Solar storms are a natural occurrence caused by high-energy particles hitting the Earth.

These clouds of particles are released in explosive outbursts from the Sun.

With the Sun in an active part of its cycle, there are concerns that some storms could disrupt technology on Earth including satellite navigation signals and aircraft communications.

How does an outburst on the Sun cause a storm on Earth?

The Sun may seem to change little from our viewing position on Earth. With the right equipment, it is possible to see dark regions called sunspots. But up close, our Sun is a dynamic, violent beast.

Bright loops of matter arch and twist like fiery fountains above the surface of this gigantic natural nuclear reactor. And every so often an intense burst of radiation called a solar flare appears when magnetic energy - stored in our star's atmosphere - is suddenly released.

Solar flares are sometimes associated with the release of high energy particles into space - eruptions that are known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), though these can also occur on their own.

A large CME can contain billions of tonnes of gas and other matter that pours into space at several million km per hour. The charged particles in this cloud stream towards any planet or spacecraft in its path.

When these particles collide with the Earth, they can cause a geomagnetic storm - a disturbance in the magnetic sheath (or magnetosphere) that surrounds our planet, protecting its denizens from the worst effects of cosmic rays.

Why are solar storms important?

Many of the effects of charged particles hitting the Earth's magnetosphere are benign, such as polar lights - the Aurora borealis and australis.

Geomagnetic storms - often referred to as solar storms - cause these northern or southern lights to become visible at lower latitudes.

However, they also disrupt technology on Earth, such as communications systems - including those used by aircraft, satellite navigation signals and electrical power grids.

As such, they could wreak long-lasting havoc with communications and power infrastructure across the globe.

A 2008 report by the US National Academy of Sciences concluded that an extreme storm could cause up to $2 trillion in initial damages by crippling communications on Earth and causing chaos around the world.

As such, several agencies around the world are working to better understand the changing conditions near our planet - known collectively as space weather.

Forecasters at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Space Weather Prediction Center monitor activity using data from a network of sensors, including those on satellites, and US Geological Survey instruments that detect magnetic fields (magnetometers).

Why have we been hearing so much about them recently?

The Sun goes through cycles of high and low activity that repeat approximately every 11 years. It is currently gaining in activity and is expected to peak in 2013 or 2014, although nobody can be sure.

This means we can expect more solar flares and more coronal mass ejections over the next few years. The solar cycle we're currently in has been a relatively quiet one in compared with previous ones.

But that does not mean that there could not be a large event in the build up to the next "solar maximum".

Bright magnetic loops of matter can be seen in this image of a solar flare

Have solar storms had big effects in the past?

Yes. In 1994, a solar storm caused major malfunctions to two communications satellites, disrupting television and radio services throughout Canada.

In March 1989, another event caused the Hydro-Quebec power grid in Canada to go down for over nine hours. The resulting damages and loss in revenue were estimated to be in the region of hundreds of millions of dollars.

But the most significant historic event remains the great solar storm of 1-2 September 1859. This disturbance shorted telegraph wires, starting fires in North America and Europe, and caused bright aurorae to be seen in Cuba and Hawaii.

In 1859, our technological infrastructure was in its infancy, but a storm with the magnitude of the so-called Carrington Event would be much more damaging today.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk

- Published9 March 2012

- Published24 January 2012