Solar storm passes without incident

- Published

A solar storm in the Earth's magnetic field has passed by the Earth with minimal effects, experts say.

"The freight train has gone by, and is still going by, and now we're just watching for how this is all going to shake out," said Joseph Kunches, a scientist with US weather agency Noaa.

The last of the charged particles from the Sun will pass Earth Friday morning.

There had been fears that this "coronal mass ejection" could wreak havoc with satellites or power grids on Earth.

However, up to this point, Dr Kunches said, "all told, it's not a terribly strong event".

Some air traffic was re-routed away from polar regions on Wednesday and Thursday, but no large-scale effects of the storm have been reported.

"This week's solar storms have been stronger than those of recent years but moderate when viewed over the longer term," said Paul Cannon, director of the Poynting Institute at the University of Birmingham.

"Most technological systems appear to be behaving well so far. However, given the Sun's activity forecasters will be closely watching the geospace environment over the next few days."

The current coronal mass ejection (CME) - travelling at some 1,300km per second - began arriving at Earth on Thursday morning, after the release of two particularly strong solar flares earlier in the week.

'Wake-up call'

Activity near the Sun's surface rises and falls through an 11-year cycle that is due to peak in 2013 or 2014.

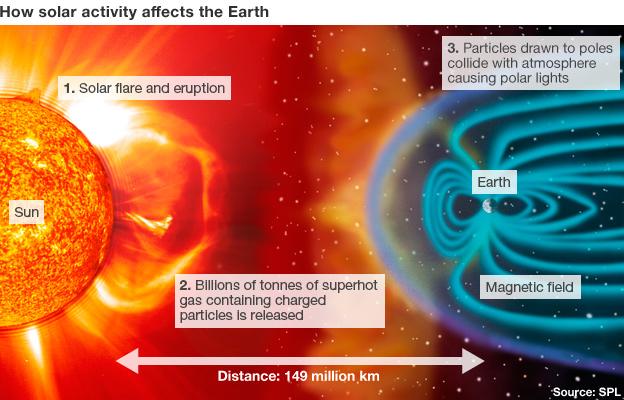

Some solar flares result in CMEs - the launch of a huge bubble of charged particles hurtling toward the Earth at speeds up to millions of kilometres per hour.

The Earth's magnetic field protects it from the constant onslaught of high-energy particles from the Sun and elsewhere in the cosmos.

However, the solar storms that mark the arrival of CMEs can disrupt the field enough to have an effect on the Earth's surface - causing current spikes in power grids or disrupting navigation devices.

Among the more benign effects is that the magnetic-field disturbance can make the Northern Lights visible at lower latitudes.

But it is often unclear, even up to the last minute, just how grave or spectacular the effects will be on Earth - that depends on the magnetic alignment of the material within the CME, which is difficult to predict.

Because different parts of the bubble can have different alignments, scientists say that the storm could still have adverse effects as it passes.

"The magnetic field in the solar wind is not facing in the direction of danger. But it could change, into the early evening," said David Kerridge, director of geoscience research at the British Geological Survey.

Although space weather scientists have seen no more significant activity since the solar flares that launched the current storm, scientists around the globe are still keeping a close watch on the Sun.

"The part of the Sun where this came from is still active," Dr Kerridge told BBC News. "It's a 27-day cycle and we're right in the middle of it, so it is coming straight at us and will be for a few days yet. We could see more material," he explained.

But regardless of its eventual extent, this episode of solar activity is a preview of what is to come in the broader, 11-year solar cycle.

Dr Craig Underwood, from the Surrey Space Centre, UK, said: "The event is the largest for several years, but it is not in the most severe class. We may expect more storms of this kind and perhaps much more severe ones in the next year or so as we approach solar maximum.

"Such events act as a wake-up call as to how our modern western lifestyles are utterly dependent on space technology and national power grid infrastructure."

Many storms are benign; this storm could enable skywatchers to see the Northern Lights from parts of the northern US and northern UK.

But the strongest storms can have other, more significant effects.

In 1972, a geomagnetic storm provoked by a solar flare knocked out long-distance telephone communication across the US state of Illinois.

And in 1989, another disturbance plunged six million people into darkness across the Canadian province of Quebec.

- Published9 March 2012

- Published7 March 2012

- Published24 January 2012

- Published16 February 2011