Thousand-year wait for Titan's methane rain

- Published

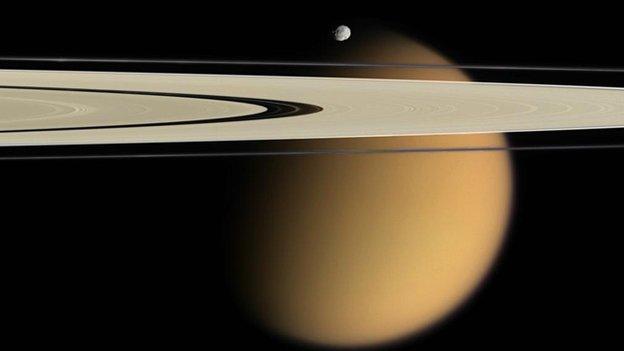

Saturn and its moons have given up many of their secrets to the Cassini mission

Places on Saturn's moon Titan see rainfall about once every 1,000 years on average, a new analysis concludes.

Earth and Titan are the only worlds in the Solar System where liquid rains on a solid surface - though on Titan, the rain is methane rather than water.

The calculation is based on findings from the Cassini probe of rainstorms that occurred in 2004 and 2010.

Dr Ralph Lorenz presented details of his work, external at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) in Texas.

Titan is a fascinating, "same but different" analogue of the Earth. Wind and rain sculpt the surface, producing river channels, lakes, dunes and shorelines.

Titan: strong methane rain, but rarely

But here, liquid hydrocarbons take the place of water. On Titan, where the surface temperature averages -179C, it rains methane.

"You get centuries between rainshowers; but when they occur, they dump tens of centimetres or even metres of rainfall," Dr Lorenz, from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL) in Maryland, told BBC News.

"That's consistent with the deeply incised river channels that we see."

These channels have been observed by both Cassini and the Huygens probe, which plunged through Titan's thick atmosphere in 2005.

Dr Lorenz says the latest results are remarkably close to the theoretical predictions of Titan rainfall he made 12 years ago.

When it rains...

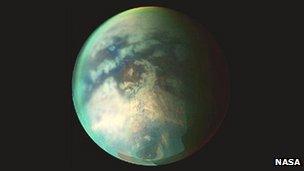

In 2004 and 2010, at different locations on Titan, the Cassini spacecraft observed a darkening of the moon's surface associated with cloud activity - events that scientists interpret as rain showers.

Dr Elizabeth Turtle, also from JHUAPL, presented an analysis of the Autumn 2010 storms observed at Concordia Regio, near Titan's equator.

"In the wake of this storm, we saw significant changes on the surface... a month later, there was this large darkened swathe that's longer than 2,000km, covering an area of about 500,000 sq km," she explained.

"The simplest interpretation is that this is caused by precipitation wetting the surface - possibly ponding in some areas.

"It's the easiest way to cover [an area this large] in such a short timescale. It's also consistent with the fact that the changes revert over several months afterwards."

Ralph Lorenz's analysis of the rainfall represents a global average; but the seasonal cycle on Titan concentrates rainfall during the polar summer.

The TiME mission will see further exploration of the Saturn system, if it is selected

Hypothetically, he says, if an observer were to sit somewhere at one of Titan's poles for 96 Earth days (six days on Titan), they would have a 50% chance of being rained on directly, and be able to observe five rainstorms.

This is of particular relevance to the proposed space mission that Dr Lorenz is currently involved with.

The Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) would splash down in one of Titan's largest lakes - Ligeia Mare - to spend 96 days analysing its depth and chemistry. It would also gather data on the surrounding environment, including weather patterns.

TiME is one of three finalists competing to be selected as a Nasa Discovery mission - the others are InSight and CHopper. A decision should be made next month.

Meanwhile, Dr Turtle's team has continued to monitor Titan, but has seen very few clouds since the events in 2010. A similar lapse was seen after the storms in 2004, and could be the result of methane in the atmosphere being depleted.

"That may be what happened here; this depleted the atmosphere significantly and it takes a while for it to reset," she said.

"We're anxious to see when we'll see clouds appearing again."

While many aspects of Earth's weather can be seen on Titan, one difference is that the moon is probably too small for the kind of activity that generates cyclones and hurricanes on Earth.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published8 April 2011