Time to choose a billion-euro space mission

- Published

- comments

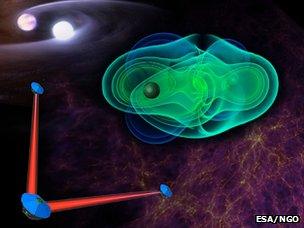

NGO would study the gravitational waves emanating from interacting supermassive black holes

It's an important week for European space science.

A key committee that advises the European Space Agency (Esa) is meeting to choose a preferred billion-euro mission to launch in the early 2020s.

They have three exciting concepts in front of them.

Juice - a mission to Jupiter and the Galilean moons

Athena - the biggest X-ray telescope ever built

NGO - a trio of high-precision spacecraft to detect gravitational waves

In terms of scope, all three missions now carry significant differences from how they were originally envisaged.

Important revisions were forced on the designers when the Americans abruptly announced in April last year that they would no longer participate.

The US space agency (Nasa) said it had different programmatic priorities and, in any case, was struggling to find the money to take part.

That bombshell was delivered after the joint mission study groups had already completed four years of feasibility work.

It meant the European members of those teams had to hurriedly reassess their ideas to make them fit within a much more constrained financial envelope.

Esa has in the order of 700m euros to spend on a "large class" mission. This covers the cost of building and launching a spacecraft. With individual member states covering the cost of the instruments on board, the total overall budget should emerge somewhere around the billion euro mark.

The agency's Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC), external has been poring over the detail of the revised mission concepts, hearing the last-chance advocacy from the competing teams on Monday.

The committee will deliver its considered recommendation to Esa's executive after some final deliberations.

That's not quite the chequered flag, however.

The executive needs to satisfy itself that the preferred candidate does indeed tick all the boxes on technical risk and cost; but assuming the directors are happy, the chosen concept will be handed to member-state delegations for the final say in early May.

It is on the conclusion of that meeting - the Science Programme Committee, external - that Esa's big mission for the 2020s will be announced; although I'll be somewhat surprised if the name of the SSAC's preference isn't in wide circulation by the end of this week.

So, the candidates are:

Juice (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer): This is the concept that has probably been least disrupted by the decision of the Americans to walk away.

Juice would be the first satellite to orbit an icy moon - Ganymede

It envisages an instrument-packed, near five-tonne satellite at launch that will be sent out to the largest planet in the Solar System, to make a careful study of three of its moons.

Juice will use the gravity of the gas giant to initiate a series of close flybys around Callisto, Europa, and then finally to put itself in a settled orbit around Ganymede. The emphasis will be on "habitability" - understanding the unique nature of these fascinating worlds and whether there is any possibility they could support life in some way.

"Its mission goal is to be the first spacecraft to go into orbit around an icy satellite," said Andrew Coates, a science team member from the Mullard Space Science Laboratory in the UK.

"Ganymede is a fascinating target. It has a magnetic field - the only moon in our Solar System that has one. It's also the biggest moon in the Solar System. It's a very exciting target because we know it has a liquid water ocean beneath its icy crust. So, part of the mission is to characterise that ocean better."

Athena X-ray telescope: We've had some very capable space observatories in the past looking at high-energy emissions coming to us from across the cosmos. Two of the them - Nasa's Chandra telescope and Esa's very own XMM-Newton telescope - continue to return excellent science.

Athena is being billed as the high-energy complement to the James Webb telescope

But Athena will dwarf these machines in terms of size.

"The focal length is 12m. That would make it the biggest X-ray telescope ever built. It is as big as we can get inside an Ariane 5 rocket," said Prof Richard Willingale from Leicester University, which would hope to be involved in the project if it flies.

"It's actually two telescopes in one, with a fixed instrument on the end of each telescope.

"It will be the high-energy astrophysics version of the James Webb Space Telescope, external [which will observe the Universe at much longer, infrared wavelengths]. We will see things that they can't.

"Primary targets would include active galactic nuclei and the black holes at the centre of them - essentially the first black holes. For the sources out there that are producing X-rays - basically, this will be a new era."

NGO (New Gravitational wave Observatory): Formally known as Lisa, this concept has had a very long gestation.

It describes three satellites, separated by a distance of a million km, which will form a high-precision interferometer.

Lasers running between the "mothership" and two outlying daughter craft will measure the very fine changes in distance between free-falling blocks inside the spacecraft.

Disturbances in these length measurements would signal the arrival of gravitational energy emitted, for example, from the interaction of supermassive black holes at the centres of colliding galaxies. It's physics at the extreme.

"The laser arm length is somewhat reduced compared with the original Lisa concept, but NGO preserves most of its science," said Prof Jim Hough from Glasgow University, which has had a major input into the design.

"NGO allows us to look at black-hole physics in a way that no other mission could easily do. It's real new science.

"NGO will work beyond the wavelengths of ground-based observatories. We can't study supermassive black holes with them in the way we'd be able to with these spacecraft. And, of course, there'll be very many tests of general relativity in what is a very extreme gravitational regime."

- Published12 March 2012

- Published4 October 2011