Alma telescope in Chile battles extreme weather

- Published

The infrastructure at the base camp suffered after being hit by strong sand storms and heavy rains

Thunderstorms, heavy rain, snow, floods and mudslides are not exactly what one would expect to see in the driest place on Earth, the Atacama Desert in Chile.

But for the past two months, these were the working conditions of the team of scientists at one of the world's biggest astronomy projects, the Atacama Large Millimeter/sub-millimeter Array (Alma).

A striking contrast from the usual sunshine and clear skies that I experienced when visiting the place just days before the mayhem started.

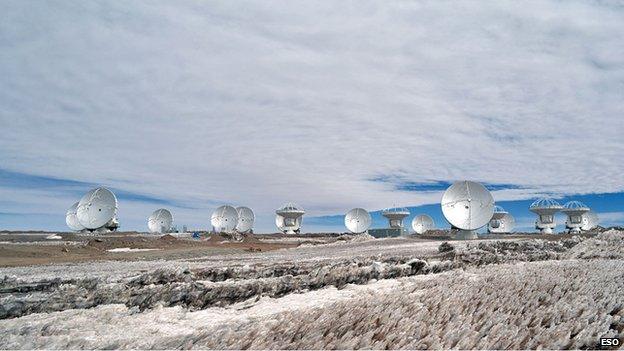

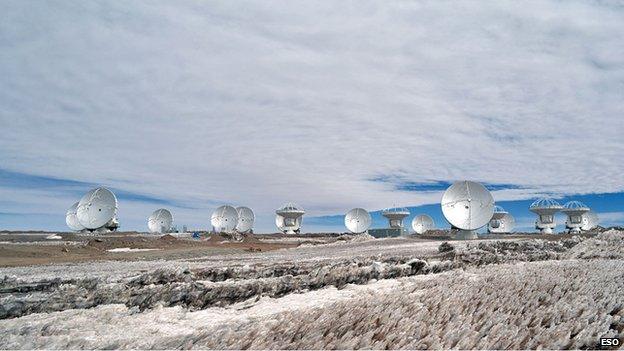

Alma is a giant radio telescope currently being built at Chajnantor plateau, the highest site in the Chilean Andes, at more than 5,000m above sea level.

The antennas managed to withstand thunderstorms and heavy rain without any damage

The construction began in 2003 and is now almost halfway complete.

Once fully operational, Alma will consist of 66 radio antennas that will probe the sky in a bid to unlock secrets of the Universe's formation.

Although the array is not finished yet, it has already delivered <link> <caption>some interesting results</caption> <altText>Alma science results</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-17539317" platform="highweb"/> </link> . Chilean researcher Cinthya Herrera has published the first science paper to come out of Alma: a study of star forming clusters that have resulted from the merger of a pair of spiral galaxies called "The Antennae".

Being a radio telescope, Alma works differently from an optical one, picking up the wavelengths of light invisible to the human eye.

"The light is composed of optical light which is what we see, but also of infrared, ultraviolet, x-rays, gamma rays, microwaves and radio waves; all of this is called electromagnetic spectrum," explains astronomer Paulo Cortes.

"Alma is interested in the millimetre and submillimetre part of that spectrum - this is the region of the cold gas from which stars form.

"By detecting the radiation emitted by that cold gas, we can understand how big structures are assembled - in other words, how stars, planets and galaxies are formed."

And this may shed light on the birth of our Universe, more than 13 billion years ago.

Alma is a joint project between Europe, North America and East Asia.

Colossal transporters were built specially for Alma

Standing among Atacama's rocks, cactuses and snow-capped volcanoes, the array's huge structures - dishes of 12m in diameter - resemble a colony of colossal white mushrooms.

Each weighs between 85 and 115 tonnes.

The antennas are packed with latest technology - and one instrument is a highly sensitive receiver, located in the centre of every 12-metre dish.

"These receivers are really cutting-edge - we've been able to reproduce in seconds the observations that usually take hours using other instruments," says Dr Cortes.

BBC Technology reporter Katia Moskvitch speaks to Brian Hoff, an Alma telescope engineer, about the potentially catastrophic consequences of a transporter dropping a giant antenna

Extreme weather

The main reason for choosing Atacama - and Chajnantor in particular - was the altitude, the extreme dryness of the air and very clear skies. Clouds appear here on average only 30 days a year.

And although some rain in the area is not unusual in February and March, no one had quite expected the latest weather.

There has not been this much water in the desert for decades, and the downpours have pushed the deadline for the project's completion back by two to three weeks, says Richard Hills, one of the astronomers on the site.

Chajnantor plateau is the so-called "high site"; even in summer time it snows up there

"It's impossible to make any observations in such conditions," he says.

"Water in the air just absorbs the astronomical signals that we're trying to observe - they simply do not make it through the atmosphere."

But thankfully, he adds, the antennas themselves have not been damaged.

The recent weather conditions are very unusual, say Alma's scientists

Unlike the devastation in a nearby village, where some 20 houses were destroyed after a particularly strong downpour in early March, the antennas managed to withstand rain, hail and snow.

They have been designed to remain operational in extremely harsh conditions, with wind speeds of up to 100km/h and temperatures as low as -25C.

Accuracy and precision

The antennas passed the weather test - to the relief of Alma's scientists, because when an antenna breaks down, repairs can be tricky.

Minor problems can be dealt with at Chajnantor Plateau, or "the high site". But in case of major issues the antenna has to be taken down to base camp on a custom-made 28-wheel transporter.

And if anything needs replacement, things get even more complicated.

"Just like for the assembly, if you miss a single screw, you have to go to the city of Calama, 100km from here, to get it," explains Silvio Rossi, an engineer at the European part of the site, run by the European Southern Observatory (Eso).

"If it's electronics, it's even worse - no other place in the world has electronics at this altitude, and it's very hard to find parts that can operate here.

Alma is surrounded by the many volcanoes of the Pacific Ring of Fire, one of which is Mount Lascar

"All parts are manufactured in Europe. For instance, the higher part of the antenna comes from Europe in two halves that have to be glued together.

"It is a one shot process - if gluing fails, we have to trash the entire part."

The process of bringing an antenna down for repairs and maintenance and up again is slow, and accuracy is vital.

It takes the colossal transporter five hours to travel 35km.

"The antennas are very sophisticated machines, and any minor bump could turn out to be a huge problem," says Brian Hoff, a supervisor at the high site.

"If you bump the antenna base, you could damage it, deflect it, and any minor damage in the order of microns of deflection - thinner than the human hair - can have catastrophic consequences [for the observations]."

Alma astronomers are now waiting for the sky to finally clear up, so that they can continue probing the space above.

<italic>Katia Moskvitch was on secondment to ESO for two months leading up to her trip to Chile</italic>

Chajnantor plateau is the so-called "high site"; even in summer time it snows up there

<italic>Katia Moskvitch was on secondment to ESO for two months leading up to her trip to Chile.</italic>

- Published30 March 2012

- Published3 October 2011