Disappointed astronomers battle on

- Published

- comments

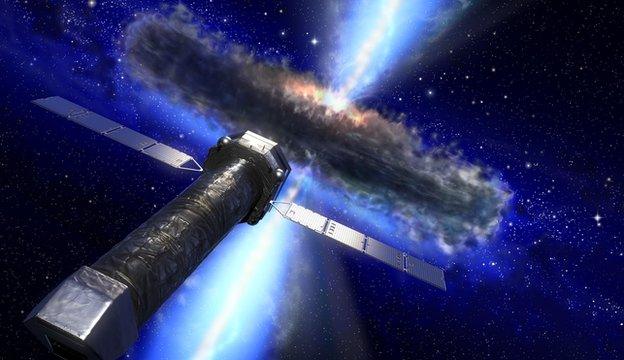

In the suite of planned next-generation facilities, Athena is meant to cover the X-ray portion of the spectrum

The fightback has begun. As soon as it became known on Wednesday that a mission to Jupiter's icy moons was in pole position to become the next big European space venture, proponents of rival concepts were on the web campaigning to try to change the outcome.

The European Space Agency's executive has recommended to member states that Juice (JUpiter ICy moon Explorer, external) be declared the winner in the competition to find a billion-euro mission to launch in 2022. The news is a bitter blow to the teams behind other proposals.

It's not just the deflation of coming second. It's also the thought of all the work that went into the proposals (five years) and the prospect that none of the promised science will be realised.

But never say never.

Prof Paul Nandra, external is from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany, with a visiting position at Imperial College London, UK.

He's a key mover behind Athena, the project to build the largest X-ray space telescope, external the world has ever seen - the absolute maximum size you could fit on the top of a mighty Ariane 5 rocket, something like 13m in length.

Athena would have the sensitivity and resolution to elucidate the extraordinary and extreme physics at the edge of a black hole like no other mission before it.

Prof Nandra heard officially on Tuesday that Juice had pipped his project for the recommendation.

On Wednesday, he set up a campaign site, external to get the world's astronomers to weigh in behind Athena in the hope - even at this late stage - of a different outcome to the competition.

He sent an email to a core list of Athena supporters at 15:30 CEST (14:30 BST) and in less than five hours he had 640 astronomers signed up, including more than 110 professors.

"It was obviously disappointing to hear the news, given how hard we'd worked and how strong a case we feel we made. We just felt we needed to do something about it, to keep on making that case. I recognise it's an uphill struggle but the final decision is not made until it's made, so to speak," says Prof Nandra.

But what chance really is there of a different outcome? Esa has a process. When it calls for mission ideas, it whittles down the many brilliant proposals it receives on the advice of specialist scientific panels.

The different disciplines review the best concepts in their areas of expertise, before pushing their thoughts up to a super panel (the Space Science Advisory Committee, external) to pick the most meritorious suggestion from across the board.

Esa's executive reviews the decision to check the chosen concept:

is technically feasibly

can be done in a reasonable timeframe

is financially affordable

and really does have the commitment of international partners if they're integral to the project.

If those conditions are met, it then passes its recommendation on to member states for the final say.

The decision-making body (the Science Programme Committee, external), due to meet on 2 May, is sovereign and can decide what it believes is best. It could go against the painstaking process that has taken five years to produce a result, but no-one I've spoken to really expects that to happen.

The setback for Athena is not just a setback for X-ray astronomy; it's a setback for the wider science.

The funding agencies plan a suite of next-generation facilities to examine the outstanding questions in astronomy across the electromagnetic spectrum, with most becoming operational in the 2020 timeframe:

the Square Kilometre Array, external in the radio

Alma, external in the (sub)millimetre

James Webb Space Telescope, external and the E-ELT, external in the near-infrared and optical

and the Cherenkov Telescope Array, external in gamma-rays.

X-rays will be the glaring omission.

"Athena would give us unique information about the Universe that you can't acquire any other way. While everyone is somewhat parochial in advocating their own wavelength range, the idea that you would be missing something entirely really resonates with the community. I think that's why we've got so many people signing up to support us from across astrophysics," says Prof Nandra.

If Juice is indeed selected as Europe's next big thing, it should launch in 2022. The great distance to the gas giant means it will not arrive at the Jovian System until 2030.

And here's the splendid irony. The Athena team will re-enter its proposal in the follow-on Esa competition which is expected to call for ideas next year. The winner would probably get a launch slot in 2028. So, even if Prof Nandra and colleagues cannot get the SPC to do an about-turn, there's still a possibility their dream will realise its science before we get pictures of those icy moons from Juice.