Key tests for Skylon spaceplane project

- Published

- comments

The pre-cooler demonstration is a major step in proving the Skylon concept

UK engineers have begun critical tests on a new engine technology designed to lift a spaceplane into orbit.

The proposed Skylon vehicle would operate like an airliner, taking off and landing at a conventional runway.

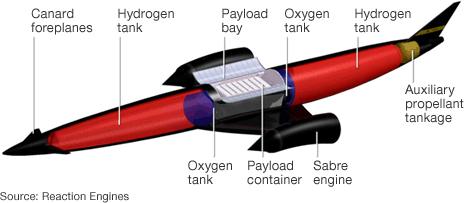

Its major innovation is the Sabre engine, which can breathe air like a jet at lower speeds but switch to a rocket mode in the high atmosphere.

Reaction Engines Limited (REL) believes the test campaign will prove the readiness of Sabre's key elements.

This being so, the firm would then approach investors to raise the £250m needed to take the project into the final design phase.

"We intend to go to the Farnborough International Air Show in July with a clear message," explained REL managing director Alan Bond.

Alan Bond, REL managing director: "These are real engine modules we are building"

"The message is that Britain has the next step beyond the jet engine; that we can reduce the world to four hours - the maximum time it would take to go anywhere. And that it also gives us aircraft that can go into space, replacing all the expendable rockets we use today."

To have a chance of delivering this message, REL's engineers will need a flawless performance in the experiments now being run on a rig at their headquarters in Culham, Oxfordshire.

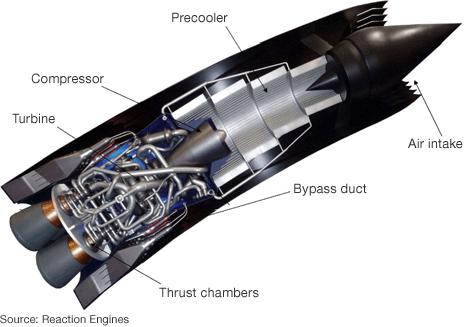

The test stand will not validate the full Sabre propulsion system, but simply its enabling technology - a special type of pre-cooler heat exchanger.

Sabre is part jet engine, part rocket engine. It burns hydrogen and oxygen to provide thrust - but in the lower atmosphere this oxygen is taken from the atmosphere.

The approach should save weight and allow Skylon to go straight to orbit without the need for the multiple propellant stages seen in today's throw-away rockets.

Dr Mark Ford: "If the engine works, it enables everything else"

But it is a challenging prospect. At high speeds, the Sabre engines must cope with 1,000-degree gases entering their intakes. These need to be cooled prior to being compressed and burnt with the hydrogen.

Reaction Engines' breakthrough is a module containing arrays of extremely fine piping that can extract the heat and plunge the intake gases to minus 140C in just 1/100th of a second.

Ordinarily, the moisture in the air would be expected to freeze out rapidly, covering the pre-cooler's pipes in a blanket of frost and compromising their operation.

But the REL team has also devised a means to stop this happening, permitting Sabre to run in jet mode for as long as is needed before making the transition to a booster rocket.

Sabre engine: How the test will work

Groundbreaking pre-cooler

Groundbreaking pre-cooler

1. Pre-cooler

During flight air enters the pre-cooler. In 1/100th of a second a network of fine piping inside the pre-cooler drops the air's temperature by well over 100C. Very cold helium in the piping makes this possible.2. Jet engine

Oxygen chilled in the pre-cooler by the helium is compressed and burnt with fuel to provide thrust. In the test run, a jet engine is used to draw air into the pre-cooler, so the technology can be demonstrated.3. The silencer

The helium must be kept chilled. So, it is pumped through a nitrogen boiler. For the test, water is used to dampen the noise from the exhaust gases. Clouds of steam are produced as the water is vapourised.

On the test rig, a pre-cooler module of the size that would eventually go into a Sabre has been placed in front of a Viper jet engine.

The purpose of the 1960s-vintage power unit is simply to suck air through the module and demonstrate the function of the heat exchanger and its anti-frost mechanism.

Helium is pumped at high pressure through the module's nickel-alloy piping.

The helium enters the system at about minus 170C. The ambient air drawn over the pipes by the action of the jet should as a consequence dip rapidly to around minus 140C.

The next few weeks will see some intense activity in the REL control room

Sensors will determine that this is indeed the case.

The helium, which by then will have risen to about minus 15C, is pushed through a liquid nitrogen "boiler" to bring it back down to its run temperature, before looping back into the pre-cooler.

"It is important to state that the geometry of the pre-cooler is not a model. That is a piece of real Sabre engine," said Mr Bond.

"We don't have to go away and develop the real thing when we've done these tests; this is the real article."

The manufacturing process for the pre-cooler technology is already proven, but investors will be looking to see that the module has a stable operation and can meet the promised performance.

The BBC was given exclusive access to film the rig in action.

Because REL is working on a busy science park, it has to meet certain environmental standards.

This means the Viper's exhaust goes into a silencer where the noise is damped by means of water spray.

The exhaust gases are at several hundred degrees, and so the water is instantly vaporised, producing huge clouds of steam.

Anyone standing outside during a run gets very wet because the vapour rains straight back down to the ground.

Future direction

The REL project has generated a lot of excitement. One reason for that is the independent technical audit completed last year.

The UK Space Agency engaged propulsion experts at the European Space Agency (Esa) to run the rule over the company's engine design.

David Shukman watches the Skylon engine test

Esa's team, which spent several months at Culham, found no obvious showstoppers.

"Engineering is never simple. There are always things in the future that need to be resolved - problems crop up and you have to solve them," said Dr Mark Ford, Esa's head of propulsion engineering.

"The issue is, 'do we see anything fundamental from stopping this engine from being developed?', and the answer is 'no' at this stage.

"The main recommendation we made is that we would like next to see a sub-scale engine - so, a smaller version than the final engine - being tested.

"So far we've looked at critical component technologies. The next step is to put those technologies together, build an engine and see it working.

"We want a demonstration of the thermodynamic cycle. We'd also like to see the engine operating in air-breathing and rocket mode, and the transition between the two."

This sub-scale engine is one of the activities proposed for the next phase of the project.

Also included is a series of flight test vehicles that would demonstrate the configuration of the engine nacelles - the air intakes.

Additionally, updated design drawings would be produced for the Sabre engine and the Skylon vehicle.

So far, 85% of the funding for Reaction Engines' endeavours has come from private investors, but the company may need some specific government support if it is to raise all of the £250m needed to initiate every next-phase activity.

"What we have learned is that a little bit of government money goes a long way," said Mr Bond.

"It gives people confidence that what we're doing is meaningful and real - that it's not science fiction. So, government money is a very powerful tool to lever private investment."

This public seed fund approach to space has certainly found favour recently within government.

Ministers put more than £40m into developing the communications payload for the first satellite operated by the Avanti broadband company, and they are giving more than £20m to SSTL to make a prototype radar satellite.

A concept drawing of the Sabre engine with a series of pre-cooler modules

- Published27 April 2012

- Published24 May 2011

- Published24 May 2011