Skylon: A British dream of space

- Published

- comments

David Shukman watches the Skylon engine test

I'm listening to a countdown. Not in the steamy Florida heat of Cape Canaveral. Or the desert winds of Baikonur in Kazakhstan. Instead this one is under way in a makeshift cabin under drizzly skies in a corner of Oxfordshire.

Some great inventions began in humble surroundings - think Bill Gates and Steve Jobs toiling in their garages - so I'm not being critical.

But as the seconds tick away to the firing up of a revolutionary new British space engine, it's hard not to speculate on its chances of success.

The engine is for the Skylon project, an ambitious scheme for a craft that would realise a long-cherished dream: to fly non-stop from airport to cosmos.

Skylon reminds me of the optimistic days of my childhood when 60s Britain, still humming with aeronautical self-belief, built its own rockets and supersonic warplanes.

Concorde was in the air and it was every schoolboy's conviction that the next inevitable step would see Union Jacks flying in space.

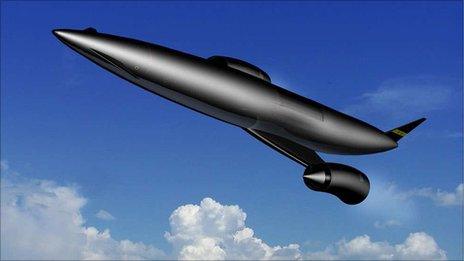

The concept looks pleasingly retro: streamlined, black, Dan Dare sleek. Stubby wings carry two curiously curved engines.

The craft is meant to speed off a runway and accelerate gracefully into orbit in a single blast, perform a task like launching a satellite and then glide back home to its hangar.

A computer animation makes it look easy: no booster rockets, no waste of abandoned fuel tanks, no costly palaver at the launch pad.

A genuine space plane, Skylon would do what the Space Shuttle never could: offer affordable and regular service into orbit.

The key is a unique motor, the Sabre, which serves as jet engine and rocket rolled into one.

Its critical component is an ingenious device that can cool the incoming air almost instantaneously.

At Mach 4 or 5, the air flow would become dangerously hot but this heat exchanger - consisting of a dense and closely-guarded bundle of tiny tubes - would chill things down to a manageable temperature in milliseconds.

Skylon would be repeatedly reusable

This would allow the jet engine to operate at up to five times the speed of sound - an achievement in itself - and make use of the supply of oxygen drawn from the air.

That in turn means less liquid oxygen needs to be carried to oxidize the fuel.

Clever stuff - and potentially game-changing.

Every space launch for the past 60 years has involved blasting off vertically and jettisoning separate stages once the fuel they carry is exhausted.

Skylon would transform all that and last year it passed a key test: a lengthy study by the European Space Agency, funded by the UK government, could not find any obvious obstacles.

It was not an official endorsement but, significantly, it was not a rejection.

So the ambition of a runway-to-orbit craft is not wishful thinking.

It is judged to be technologically plausible, and the tests we are witnessing are designed to prove it.

At the end of the countdown there's a brief silence. But not for long. Within a few seconds the engine roars into life.

Determined optimism

A cloud of steam shoots into the air. The little cabin shakes and feels like it might lift off. We've been briefed on where to muster for safety if the device explodes: basically, get away.

The experiment runs for a noisy 360 seconds. The team are optimistic their design will work.

The mastermind, Alan Bond, is determined. He needs to be: he's been involved in the concept since the early 80s, when it was called Hotol, constantly struggling with funding while keeping alive a flame of belief that Skylon represents the future.

Amid the din, my mind wanders to a few other great British inventions, and their fates.

When the last Concorde came into land at Heathrow, I was standing in a field right below it - a high adrenaline moment - but the noise was literally breathtaking.

And that was the plane's undoing. Everyone admired the beautiful lines, and for a while supersonic passenger travel was a reality, but few countries would tolerate the racket so the wonder jet died and no one has tried to replace it.

Will Skylon prove more popular?

On Christmas morning 2003, another feat of British technological wizardry was in action.

Beagle disappointment

The tiny Beagle-2 spacecraft, packed with innovative equipment to search for signs of life, was descending to the surface of Mars.

Like Skylon, it had taken real chutzpah to win support. Also like Skylon, Beagle offered the chance of leapfrogging ahead of Nasa. It had a lot going for it.

But in the dark of that fateful day we waited for a signal. And waited. No news was bad news: the little space-chic craft, carrying a painting by Damian Hirst and an audio test signal by Blur, vanished without trace.

And in the icy wastes of northern Sweden, I witnessed the death of Britain's chances of being a space power in its own right.

The last truly British rocket, a spindly machine with the delightful name of Skylark, was about to be launched from ESA's Arctic range at Kiruna. It was 2005.

The Skylark was the end of a line that had begun back in headier days of the 1950s. Government funding had then dried up. A hardy band had kept the final batch going, lofting experiments for a few gravity-free minutes.

But long before then the Americans, Russians and Europeans had made massive, well-funded advances and British interest dwindled.

Funding issues

So can Skylon rekindle that dream?

To succeed, it needs to capture a healthy slice of the market for satellite launches. That's the biggest potential earner. But to do that, it must prove viable.

But that is only possible with billions in funding. Will the government provide that?

It likes the project but that kind of money is highly unlikely.

Would the European Space Agency pay? Not if it undermines its own Ariane launcher.

So will the private sector stump up? That's the hope of the project team. But would big backers emerge before they know if Skylon will actually do what it's meant to?

Engineering, however ingenious, is not enough to guarantee success; finance and politics are critical ingredients too. Britain has a thriving space industry but one that focuses on satellites and sensors, not spaceflight.

We step outside. The steam has cleared. Wearing a helmet and face shield, I'm allowed to stand close to the miracle engine. I think aloud as I work out what to say on camera.

Alan Bond, standing close by, hears me say that Skylon 'could make space travel easier.'

He intervenes. "Not 'could'," he says. "It's not 'Skylon could make space travel easier'. It's 'Skylon will make space travel easier'."

I like the team and their ambition and their Britishness. And I admire their grit in the face of so many obstacles.

Alan Bond may yet be proved correct. But right now we really can't tell if his dream will soar beyond Oxfordshire.

- Published27 April 2012

- Published24 May 2011

- Published24 May 2011

- Published31 January 2011