GM wheat scientists at Rothamsted make plea to protesters

- Published

An earlier protest against GM wheat saw "mutant pasties" handed in to government offices

Scientists developing genetically modified wheat are asking campaigners not to ruin their experimental plots, but come in for a chat instead.

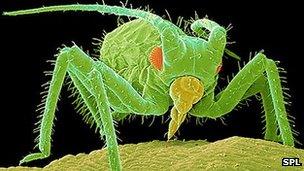

The trial at Rothamsted Research in Harpenden, Herts, uses wheat modified to deter aphids, an insect pest.

The protest group Take the Flour Back has vowed to "decontaminate" the site unless the research is halted.

The scientists say the GM plants could benefit the environment as they will reduce pesticide use.

"We appeal to you as environmentalists," they write in an open letter.

"Our GM wheat could, for future generations, substantially reduce the use of agricultural chemicals."

But the campaigners say the GM trial presents "a clear risk to British farming".

They argue that genes from the modified strain could spread into neighbouring fields, and that there has been no evaluation of whether foods made from the GM variety would be safe to eat.

They are planning a day of action on 27 May, trailed on their website as "a nice day out in the country, with picnics, music... and a decontamination".

Full package

Rothamsted's wheat contains genes that have been synthesised in the laboratory - an approach that is becoming more commonplace than transferring genes from other organisms, as technology develops.

Lucy Harrap, Take the Flour Back: "Cross contamination issues are important"

The gene will produce a pheromone called E-beta-farnesene that is normally emitted by aphids when they are threatened by something.

When aphids smell it, they fly away.

"Also, the natural enemies of aphids - ladybirds, lacewings and a particular parasitic wasp - when they smell this smell, they're attracted," said Prof Huw Junes, one of the study team who signed the open letter.

"So it's potentially got an advantage in the UK and other western nations because it'll prevent the need to spray insecticide - and [in the developing world where] farmers don't have access to insecticide, they'd have that packaged up in the seed."

However Lucy Harrap from Take the Flour Back doubted the crop's environmental credentials.

Aphids are a major threat to cultivation in the UK and other countries

"So far, the evidence doesn't indicate that GM fields need less pesticide - in fact they tend to need more," she said.

"The other thing is that they're using an antibiotic resistance gene as a marker in this trial, and in many parts of the EU that's considered quite outdated science now because you can get gene transfer into bacteria and so on."

The group's publicity material suggests the crop contains a cow gene. Its logo is a cow's head with a body in the shape of a loaf.

The gene in question - a promoter gene, which switches on other genes - is a synthetic variant of one found in many organisms, including wheat itself.

The researchers explained that they chose a variant closer to the cow version than the wheat one in order to prevent other genes in the wheat recognising its activity and regulating it.

E-beta-farnesene itself is produced naturally by a number of plants including peppermint and potatoes.

Security concerns

Most biotech crops grown across the world are proprietary to big commercial companies such as Monsanto and Syngenta.

Scientists believe GM wheat could help feed hungry mouths - campaigners think the opposite

In contrast, the Rothamsted letter pledges their results "will not be patented and will not be owned by any private company.

"If our wheat proves to be beneficial we want it to be available to farmers around the world at minimum cost," they write.

They are inviting campaigners in for a discussion.

"You have described genetically modified crops as 'not properly tested'," they write. "Yet when tests are carried out you are planning to destroy them before any useful information can be obtained.

"We do not see how preventing the acquisition of knowledge is a defensible position in an age of reason."

Ms Harrap told BBC News that her group is already aware of Rothamsted's position and arguments and is in the process of replying to an earlier, less detailed letter.

Prof John Pickett, leader of the research team, defended the experiment

She also said that the Rothampsted scientists are aware of critiques from science-based opponents of GM technologies such as the group GM Freeze.

Her group does not oppose research, she clarified - but full safety tests should be done before crops are planted outdoors.

She doubted whether "decontamination" would occur on 27 May, given security around the site.

Calling on campaigners publicly not to destroy crops and appealing on the basis of GM crops' environmental credentials is a relatively new tactic for scientists, and was deployed with some success by The Sainsbury Laboratory in Norwich last year.

Protests were held under the banner Take the Spuds Back. But no attempt was made to destroy the site where a trial of a potato modified to resist potato blight, the fungal disease behind the Irish famine of the late 1840s, has entered its third and final year.

Polls continue to indicate a deepset resistance to GM food, in the UK and most of Europe.

Follow Richard <link> <caption>on Twitter</caption> <url href="http://twitter.com/#!/BBCRBlack" platform="highweb"/> </link>

- Published17 April 2012

- Published28 March 2012

- Published24 February 2012

- Published6 July 2011