Still waiting to catch the gravitational wave

- Published

- comments

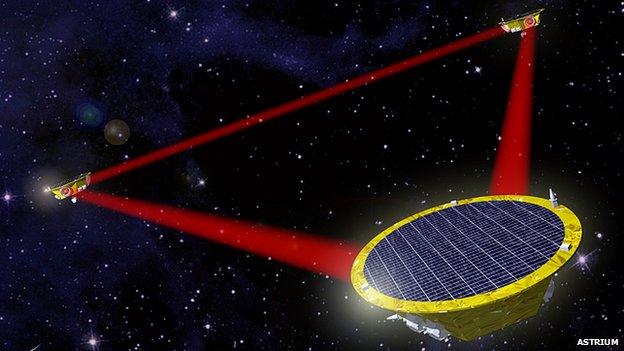

The full Lisa system calls for a widely separated, three-arm laser system

European Space Agency (Esa) member states have decided to select a mission to Jupiter and its icy moons as their next great venture.

Juice, as the spacecraft is currently known, will leave Earth in 2022 on a long journey that should see it returning science from the outer Solar System in the 2030s.

The champagne corks will be popping in the planetary science community, but there'll be a sense of deflation in those disciplines that had their projects overlooked this time.

I've already considered the consequences for high-energy astronomy and the rejection of the Athena X-ray telescope concept. And so for this posting, I want to look at the other big loser in the competition - the mission that would seek to detect gravitational waves in space.

If everybody's second favourite football team is Barcelona then perhaps the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (Lisa), external is everyone's second favourite space mission.

Time and again over the past few years I've been told "if my mission isn't selected, I hope Lisa wins".

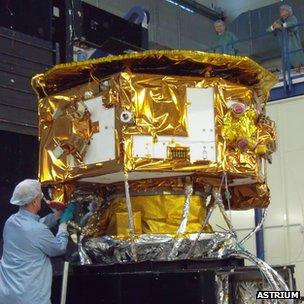

Lisa Pathfinder will test critical technologies

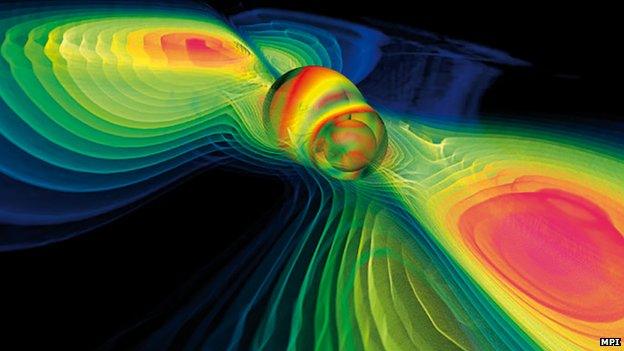

Gravitational waves, external are an inevitable consequence of Einstein's general theory of relativity, external. They describe the disturbance in space-time resulting from an accelerating body. Extreme events such as exploding stars and merging black holes should send gravitational energy radiating outwards at the speed of light.

Unlike electromagnetic waves - the light seen by traditional telescopes - gravitational waves are extremely weak, and that makes them very hard to detect.

If one were to pass through your body it should simultaneously stretch your space in one direction whilst squashing it in a direction that is at right angles.

Current Earth-based observatories hunting for this disturbance bounce lasers down L-shaped tunnels that are hundreds, external or thousands, external of metres long. And their instrumentation is fantastically sensitive, aiming to find deviations that can be equivalent to one one-thousandth of the width of a proton, one of the particles that make up all atoms.

The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna mission would do something very similar in space - but with three spacecraft flying five million km apart in an equilateral triangle formation. The concept has been studied for the better part of 20 years.

Lisa got through to the final run-off in Esa's competition, and then, like Juice and Athena, was forced to modify its architecture to reduce costs when the Americans withdrew their co-operation in April 2011.

As a consequence, Lisa lost one side of its laser triangle and some sensitivity, and was renamed NGO for New Gravitational wave Observatory, external.

Gravitational waves are a consequence of Einstein's general theory of relativity

But everyone you speak to still says it represented marvellous science. So why did it lose out?

There're probably a few reasons, and I'll try to summarise the comments that have been made to me.

One was the price tag. Even in its remodelled format, the mission would have cost Esa more than 1,000 million euros (the Lisa/NGO team disputes the reality of this figure) and this was substantially above the ceiling of 650 million the agency had set.

Another reason was launch readiness. Esa's executive did not believe the mission could be made ready before 2025, and it wants to maintain a certain flight cadence for its science projects, ie Esa needs to be seen to be doing stuff regularly.

And there is no doubting that this remarkable proposal was hurt in the eyes of some observers by the fact that its precursor mission has yet to fly.

The Lisa Pathfinder spacecraft, external being built in the UK will test a number of critical technologies in orbit but it won't get into space until 2014 at the earliest.

Prof Bernie Schutz from the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, external (Albert Einstein Institute) in Potsdam and Hannover has been a key player in the Lisa/NGO project. He believes the delay in getting Pathfinder into space has been damaging.

Ground-based facilities are being expanded with a first detection predicted to be just a few years away

"It's not explicit in any of the documents I've seen, but I think the fact that Lisa Pathfinder has not flown yet was a big uncertainty in the minds of Esa's Space Science Advisory Committee [which ranked the missions], and it didn't take much added uncertainty to make them decide to wait," he told me.

"So, the most important thing is that when Esa runs the next competition, it does so after Lisa Pathfinder has flown. Then everyone will know that Lisa or NGO - whatever the configuration is - will be viable."

A few people have said to me in recent weeks that Lisa is such an astonishing mission that they want it to be flown in its full configuration; and that perhaps NGO being rejected this time is something of a blessing.

The Juice mission to Jupiter and its moons has been chosen as the next large class venture

"I understand that; there's a small voice in my head too that has some sympathy with that position," conceded Prof Schutz. "But the most important thing is that we get this field going, because once we've pioneered it there'll be so many discoveries that it will only motivate further missions. So, whether we fly as Lisa or as NGO, it makes no difference.

"But there is another side to this. Had we been selected, we would have had two or three years of further study, and that would have been time when we could have explored the possibility of bringing in international partners, including even Nasa.

"And it wouldn't take very much resource to re-instate the third arm. Getting rid of the third arm was done basically to make sure we had adequate margin on weight and cost so that we wouldn't scare anybody.

"It was definitely our view that with more time, and just a small contribution from Nasa, we could have put the third arm back in. We could have got very close to the full Lisa had we been selected."

When gravitational wave observatories are working at the required sensitivity - both on the ground and in space - they will turn science on its head. They will give us an utterly new way to study astrophysical phenomena, one that is not depended on the light telescope.

We will be able to probe regions and epochs in the cosmos that are beyond that old fangled technology. Lisa's time will come. We just have to wait a little bit longer.