Arctic melt releasing ancient methane

- Published

Many of the sites were bubbling methane that has been stored for millennia

Scientists have identified thousands of sites in the Arctic where methane that has been stored for many millennia is bubbling into the atmosphere.

The methane has been trapped by ice, but is able to escape as the ice melts.

Writing in the journal Nature Geoscience, the researchers say this ancient gas could have a significant impact on climate change.

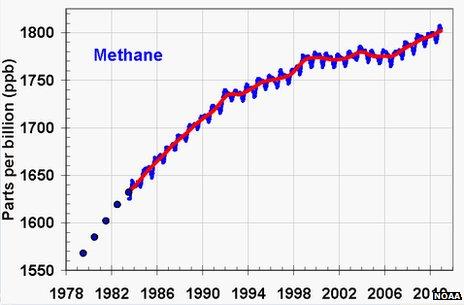

Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas after CO2 and levels are rising after a few years of stability.

There are many sources of the gas around the world, some natural and some man-made, such as landfill waste disposal sites and farm animals.

Tracking methane to these various sources is not easy.

But the researchers on the new Arctic project, led by Katey Walter Anthony from the University of Alaska at Fairbanks (UAF), were able to identify long-stored gas by the ratio of different isotopes of carbon in the methane molecules.

Using aerial and ground-based surveys, the team identified about 150,000 methane seeps in Alaska and Greenland in lakes along the margins of ice cover.

Local sampling showed that some of these are releasing the ancient methane, perhaps from natural gas or coal deposits underneath the lakes, whereas others are emitting much younger gas, presumably formed through decay of plant material in the lakes.

"We observed most of these cryosphere-cap seeps in lakes along the boundaries of permafrost thaw and in moraines and fjords of retreating glaciers," they write, emphasising the point that warming in the Arctic is releasing this long-stored carbon.

"If this relationship holds true for other regions where sedimentary basins are at present capped by permafrost, glaciers and ice sheets, such as northern West Siberia, rich in natural gas and partially underlain by thin permafrost predicted to degrade substantially by 2100, a very strong increase in methane carbon cycling will result, with potential implications for climate warming feedbacks."

Atmospheric methane concentration is rising again after a plateau of a few years

Quantifying methane release across the Arctic is an active area of research, with several countries despatching missions to monitor sites on land and sea.

The region stores vast quantities of the gas in different places - in and under permafrost on land, on and under the sea bed, and - as evidenced by the latest research - in geological reservoirs.

"The Arctic is the fastest warming region on the planet, and has many methane sources that will increase as the temperature rises," commented Prof Euan Nisbet from Royal Holloway, University of London, who is also involved in Arctic methane research.

"This is yet another serious concern: the warming will feed the warming."

How serious and how immediate a threat this feedback mechanism presents is a controversial area, with some scientists believing that the impacts will not be seen for many decades, and others pointing out the possibility of a rapid release that could swiftly accelerate global warming.

Follow Richard <link> <caption>on Twitter</caption> <url href="http://twitter.com/#!/BBCRBlack" platform="highweb"/> </link>

- Published17 March 2012

- Published6 January 2011