Shortages: Metals in demand

- Published

Demand for metals will surely increase - but it's impossible to predict by how much

There was an outcry in the UK last month when metal thieves stole a plaque dedicated to two children killed by an IRA bomb attack in Warrington.

It was the latest in a pandemic of metals thefts: lead from church roofs, copper from railway cables.

Does this mean we're reaching a shortage of these metals? No - it just means they have attained a value that makes a low-risk crime worthwhile.

Will we suffer a shortage of metals as the world population grows and gets richer? That's a different and difficult question.

Demand for metals will surely increase - but it's impossible to predict by how much because shortage is determined by a complex equation involving demand, availability, cost of extraction and processing, technology improvement and substitutability - all of them influenced by the state of the economy.

First, availability: we can't say how much metal lies in the earth's crust, and the more we seek the more we find.

Many new finds, though, are dilute. Copper ores used to contain as much as 30% copper. Now firms are having to smash rocks containing as little as 1% of copper.

So it's highly likely that future metals will be increasingly expensive.

New technologies for extraction may mitigate the cost, though. In Chile, <link> <caption>for instance, they're developing bio-mining</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-17406375" platform="highweb"/> </link> - a process which uses bacteria to liberate copper from rocks, saving money and energy.

Future demand for metals will depend on the state of economic development and spread of wealth.

It'll also depend on substitutes being found. In Michigan in the US for instance a firm's attempting to slash the cost of carbon fibre for it to be used in wind turbine blades.

This lightweight substitution removes the need of steel for the blades and reduces the need for steel in the turbine tower. Another firm is super-hardening steel so less of it needs to be used.

Advances like these are hard to predict. It's also impossible to foretell which minerals will suddenly come into fashion.

Gold dust

A report by the UK think-tank Green Alliance collated seven recent studies on mineral shortage.

Iron and aluminium are so abundant they didn't get a mention. There was little concern expressed for copper, silver or chromium.

But there were substantial worries over the minerals that are gold dust for the new economy: antimony, used in flame-retardants and micro-electronics; the platinum group of metals, used in catalytic converters, fuel cells, phones and hard discs; and lithium, used in batteries.

Indium was a greater concern still - it's used in flat screens and touch screens.

The market price of some rare earths jumped by 2,000% in a year.

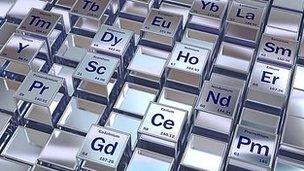

But the greatest anxiety was over the group of <link> <caption>metals known as rare earths</caption> <url href="www.bgs.ac.uk/downloads/start.cfm?id=1638" platform="highweb"/> </link> whose market price jumped in some cases by 2,000% in a year.

Rare earths used in fluorescent lamps help save energy. The rare earth lanthanum's in demand for hybrid car batteries.

Neodymium, dysprosium and praseodymium <link> <caption>improve efficiency</caption> <url href="www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/POST-PN-368.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> of high power magnets, electric vehicles and wind turbines.

Rare earths are not actually rare but the fears developed because China, which has the biggest deposits, spooked businesses by imposing export restrictions, saying that they were needed for the domestic manufacturers.

There's been a rush to produce rare earths in other countries and the price slumped in the recession so those anxieties have ebbed a little.

But the threat of shortage rarely fails to provoke a reflexive reaction and the mini-crisis prompted policy-makers to ponder how we can recycle more of the metals we use.

Double paradox

This is <link> <caption>easier said than done</caption> <url href="http://www.unep.org/resourcepanel/Portals/24102/PDFs/Metals_Recycling_Rates_110412-1.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> , with economics, technology and societal attitudes all at play.

Aluminium, which is cost-effective and easy to recover, is recycled globally at just 60-70% because it's hard to set up comprehensive collection systems. Copper is recycled at only 40% even though 99% is potentially reusable.

When it comes to the metals embedded in complex products like phones, circuit boards and screens the task is much harder. And the more cars become <link> <caption>computers on wheels</caption> <url href="http://www.green-alliance.org.uk/reinventing_the_wheel/" platform="highweb"/> </link> the less easy it is to shred them and retrieve the metal.

Designers are being urged to make products that can be dismantled and are recyclable but this often means increasing the weight and use of materials.

And there's a double paradox. The more designers reduce the amounts of metals in products, the less worthwhile it is to recycle them.

And even if we do get smarter about <link> <caption>recycling the metals</caption> <url href="http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/static/documents/Business/EPOW-recovering-critical-raw-materials-T5v2.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> in the shortest supply it won't keep up with the predicted increase in demand.

There's another factor, too - the environment. As we're mining metals in greater dilution we're using more and more energy and water - commodities themselves under ever-increasing pressure.

Like so many other stress factors for the world, metals don't exist in isolation. And it's the combination of stresses that gives many analysts such cause for concern.

- Published20 June 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published13 March 2012