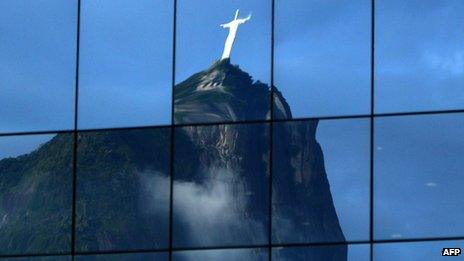

Rio+20 deal weakens on energy and water pledges

- Published

The draft text at the Rio meeting identifies poverty as the greatest challenge

Governments are set to weaken pledges on boosting access to water and energy after a new draft negotiating text was issued at the Rio+20 meeting.

The text was issued by the Brazilian host government after it assumed leadership of the talks from the UN.

It affirms that nations must not slide back on prior pledges and names ending poverty as the "greatest challenge".

Brazil wants the text signed off before 130 heads of government and other ministers arrive on Wednesday.

The new text was not officially distributed to journalists, despite pledges that the meeting here was "accessible".

Preparatory talks were supposed to end on Friday evening, but at that stage only 37% of the UN's draft text had been agreed - which led to Brazil's decision to issue a revamped document.

The 50-page text, obtained by BBC News, gives developing countries much of what they have been asking for in terms of principles without agreeing to their demands for firm pledges of financial and technological assistance from the West.

In response to charges that richer countries were attempting to weaken prior commitments on aid and other issues, the text is explicit: "We emphasise the need to make progress in implementing previous commitments... it is critical that we honour all previous commitments, without regression".

"Faced with the determined efforts by some developed countries, in particular the US, to rip up the Earth Summit agreement of 1992, the text seems to have stopped us moving backwards," said Asad Rehman, head of international climate at Friends of the Earth.

"But it certainly doesn't get close to addressing the concerns of the people or our planet.

"Faced with a triple planetary crisis - climate catastrophe, deepening global inequity and unsustainable consumption driven by a broken economic system - the text is neither ambitious enough nor delivers the required political will needed."

In another move that should please developing countries, the text confirms the principle that developed and developing countries have "common but differentiated responsibilities" in moving towards sustainable development.

No firm numbers

But whereas developing countries have been demanding $30-$100bn per year in exchange for "greening" their economies, the draft text gives no firm numbers.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon's Sustainable Energy for All initiative, which aims to provide everyone on the planet with modern energy by 2030 and increase progress on renewables and energy efficiency, is only "noted" - not endorsed.

- What is the Rio summit about?

And there is no commitment to end fossil fuel subsidies, as some countries have been advocating.

On economic indicators, the text "recognises the need for broader measures of progress to complement GDP in order to better inform policy decisions", and asks UN statisticians to begin work on the issue.

"It's good that the text still recognises that rich and poor countries have different responsibilities," said Erica Carroll, Christian Aid's policy analyst.

"But we'd like to see much stronger support for work to ensure that everyone in the world has sustainable energy, and much more enthusiasm on the need for alternatives to GDP."

Many campaign groups have been urging that this summit should at the least acknowledge everyone's basic right to food and water.

An entrance-hall poster greeting Rio+20 delegates to the talks

The right to food - to which the US has objected during talks - is enshrined in the draft text, but the language on water is vaguer.

"The right to water and sanitation is essential to the full enjoyment of life and other human rights," said Farooq Ullah, executive director-designate of Stakeholder Forum, a group working to involve all stakeholders in UN sustainable development processes.

"Previous UN resolutions have had hold-outs; and one of the successes of Rio+20 has been that Canada and the UK have for the first time recognised the universal right to water and sanitation respectively - so where the Brazilians have lost this agreement is a mystery."

Groups working on ocean conservation were however pleased that the text contains commitments to end illegal and exploitative fishing, support local small-scale fishers, and set up a process that would eventually regulate fishing and protect life on the high seas.

Health care guarantees

There is implicit criticism of the EU's recent move to charge airlines for their greenhouse gas emissions, with a clause saying that countries or regional blocs should not take "unilateral actions to deal with environmental challenges outside the jurisdiction of the importing country".

Other ingredients of the new text include:

guarantees of gender equality in employment and health care

no requirement for corporations to measure and report on the sustainability of their operations, as has been included in earlier versions

a commitment to tackle youth unemployment

a limited upgrade for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), without the major elevation in status that many observers have been advocating

The Brazilian hosts say they want negotiators to finish work on the new text by the end of Monday - allowing one day's grace before the three-day summit involving heads of government begins.

Various delegations, especially the US, Canada and the powerful G77/China bloc of 131 developing countries, have previously put red lines through many elements of the new text.

They will have to give ground significantly if a deal is to be concluded.

Even if it is, it will not make the major strides towards a sustainable development path that many scientists and indeed many politicians say are necessary.

Follow Richard <link> <caption>on Twitter</caption> <url href="http://twitter.com/#!/BBCRBlack" platform="highweb"/> </link>

- Published16 June 2012

- Published15 June 2012

- Published14 June 2012

- Published13 June 2012

- Published12 June 2012