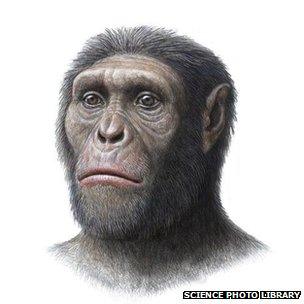

Early human ancestor chewed bark

- Published

The first Australopithecus sediba fossil was discovered in South Africa

An early relative of humans chewed on bark and leaves, according to fossil evidence.

Analysis of food trapped in the teeth of the two-million-year-old "southern ape" suggests it existed on a unique diet of forest fruits and other woodland plants.

The study, in <link> <caption>Nature</caption> <url href="http://www.nature.com/" platform="highweb"/> </link> , gives an insight into the evolution of what could have been a direct human ancestor.

Other early African contemporaries had a diet suggesting a grassland habitat.

The first fossils of <italic>Australopithecus sediba</italic>, discovered in South Africa in 2008, were hailed as a remarkable discovery.

Teeth from two individuals were analysed in the latest research, focussing on patterns of dental wear, carbon isotope data and plant fragments from dental tartar.

The evidence suggests the ape-like creature ate leaves, fruit, bark, wood and other forest vegetation.

Dr Amanda Henry of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, led the research.

"We've for the first time been able to put together three quite different methods for reconstructing diet and gotten one cohesive picture of the diet of this ancient species and that picture is really quite different from what we've seen in other hominins (human ancestors)," she said.

"That's exciting, we're seeing a lot more variation among these species than we'd expected."

Human milestone

Human ancestors from around this time period were probably exploring a wide variety of habitats.

Each species was finding its ecological niche a few hundred thousand years before the evolution of <italic> Homo erectus</italic>, which spread out of Africa into many different habitats around the world, heralding a milestone in human evolution.

Dr Henry said <italic>Australopithecus sediba</italic> walked on two legs but probably also spent time foraging in the trees.

"It was still quite primitive; it had a very small brain; it was quite short and it had fairly long arms but it was definitely related to us," she said.

Bark and woody tissues were found in the teeth

Dr Louise Humphrey of the palaeontology department at London's <link> <caption>Natural History Museum</caption> <url href="http://www.nhm.ac.uk/index.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> said there was debate about the position of <italic>Australopithecus sediba </italic>in the human lineage.

"The question is, is this a great great granddad or grandma or is it a cousin?

"They were eating bark and woody substances, which is quite a unique dietary mechanism; it hasn't been reported for any other human relative before."

The animal may have eaten fruit and young leaves when food was plentiful, but turned to less nutritious food like bark when times were hard.

However, syrup beneath the bark may have provided a sugary treat.

Dr Henry said: "A lot of people have turned their nose at the idea of eating bark but I always think that what they're eating is probably not the coarse outer bark but potentially the softer inner bark where the sap is.

"And so if you think of maple syrup - it's the sap of maple trees - then it could have been quite a tasty substance."

- Published16 November 2011

- Published8 September 2011

- Published8 September 2011