Satellites have an electric future

- Published

- comments

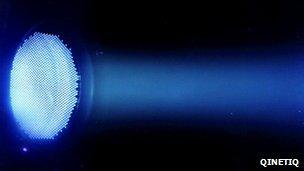

Thrust comes from a stream of charged atoms (ions) accelerated to very high velocities

One of the most interesting trends in satellite production in the next few years is likely to be the wide introduction of electric propulsion (EP), external.

More and more satellites will be launched not with chemical thrusters to manoeuvre them in space but with ion propulsion units.

We've seen electric engines fitted to scientific spacecraft in recent years, but not so much on commercial satellites.

Boeing has charged out of the box on this one, agreeing to build four "all electric" telecommunications spacecraft, external for Asian and Mexican operators.

The attraction is mass - or rather, lack of it.

Chemical thrusters require large tanks of propellant; electric engines, while they don't provide quite the same initial boost, do not need anything like the same volumes of fuel and can work for much longer.

The downside is that it takes you longer to put a satellite in its final orbital slot; the big plus, however, is that you get a much lighter satellite.

That weight saving can either be given over to more payload (transponders, external in the case of telecommunications satellites), or allow the satellite to squeeze on to a smaller, cheaper rocket.

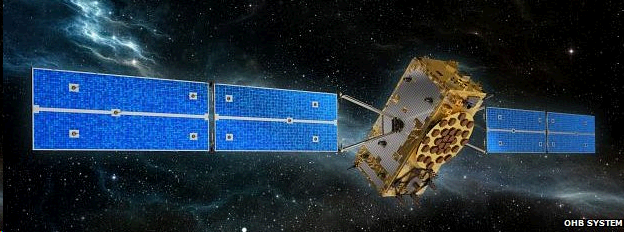

The latter strategy is the one now being looked at seriously for the future of Galileo, Europe's new satellite navigation system, external.

It needs 30 spacecraft in orbit to operate a full network (with spares); and because Galileo will be an on-going service, there will be an on-going requirement for replacement satellites.

A Galileo satellite can be produced now for a unit price of about 30m euros

Galileo, as we all know, is a hugely expensive project, costing billions of euros.

Part of that cost comes down to the price of the rockets used to get the platforms into the sky. If that could be tackled, our taxes would go further.

Currently, Galileo satellites are launched two at a time on a Russian Soyuz rocket.

It costs roughly as much to launch those two satellites as it does to build them. So, if you could get a third satellite aboard, you'd suddenly jump to a new cost regime.

This week, at the Farnborough International Airshow, external, the two companies making Europe's Galileo spacecraft put pen to paper on their contractual relationship, external.

OHB System of Bremen, Germany, and Surrey Satellite Technology Limited (SSTL) from Guildford, UK, can now turn out a Galileo satellite for about 30m euros.

That has come down from roughly 40m euros per spacecraft when they were first engaged to do the job by the European Commission and the European Space Agency.

But getting the cost down much further is really a launch issue, and electric propulsion could be the solution.

"It is feasible to take Galileo satellites up with electric propulsion, if the technology is available and mature enough," commented OHB's Ingo Engeln.

"You need more time to get the satellites in place, of course, but for the next generation this should be no problem."

And Giuliano Gatti, who works on the Galileo project for Esa, added: "It would mean you could get one satellite on Vega, three on Soyuz and up to six on the Ariane 5."

Europe has a lot of experience already in ion engines.

The concept is simple enough. Strip the electrons off a stream of xenon gas atoms so that they become charged (ions). Then put those ions in a magnetic field and accelerate them to extremely highly velocities in one direction to provide thrust for your satellite in the opposite direction.

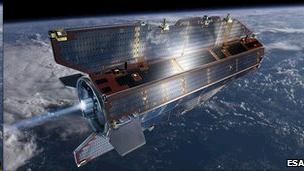

You may be aware of Goce, the European Space Agency's gravity mapping satellite. This flies so low to make its maps that it must continually fire its ion engine, external to counteract the wisps of atmosphere still present at an altitude of 260km.

It was launched in 2009 with just a 40kg tank of xenon and is still working.

Gravity mapper Goce has been firing its electric engine non stop since 2009

Of course the penalty is that ion engines put you in the slow lane.

Chemical thrusters might not burn as long, but they give you great initial acceleration and a satellite can be ejected from its rocket and be ready for use in its correct position in the sky in a matter of weeks.

With electric propulsion, it would take months.

"Where the EP variant will come into its own is in the future, once the Galileo system is in place and you have to consider replenishment, perhaps of single spacecraft," commented John Paffett.

"At the moment, Soyuz and Ariane are quite efficient ways of populating a constellation; but what if you have a single spacecraft failure?

"It makes no sense to put an additional four or six spacecraft into an orbital plane. So the question then becomes: how cheaply can you acquire a small launch vehicle, drop a satellite off in any arbitrary orbit and have EP do the transfer from there?"

The contract signed between OHB System and SSTL brings another 80m euros' worth of work to the Guildford company.

OHB also signed a contract with Culham's ABSL, external at the show. The British company will be providing the batteries that go into Galileo satellites.

- Published19 April 2012

- Published2 February 2012

- Published21 October 2011

- Published26 October 2010