Gravity satellite yields 'Potato Earth' view

- Published

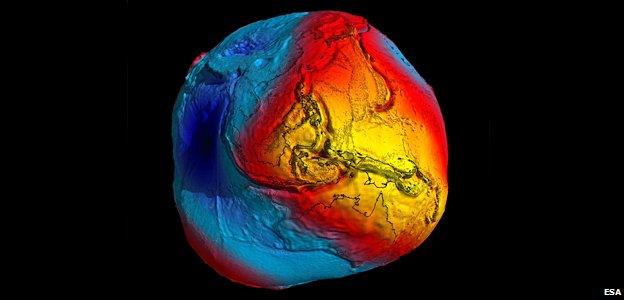

Gravity is strongest in yellow areas

It looks like a giant potato in space, and yet the information in this model is the sharpest view we have of how gravity varies across the Earth.

The globe has been released by the team working on Europe's Goce satellite.

It is a highly exaggerated rendering, but it neatly illustrates how the tug we feel from the mass of rock under our feet is not the same in every location.

We should think of this model as a map of the horizontal, or "virtual sea-level", say scientists.

The data gathered by the super-sleek space probe is bringing a step change in our understanding of the force that pulls us downwards and the way it is shaping some key processes on Earth.

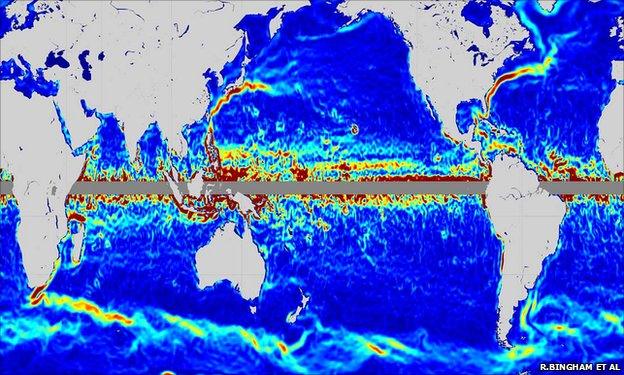

Chief among these new insights is a clearer view of how the oceans are moving and how they redistribute the heat from the Sun around the world - information that is paramount to climate studies.

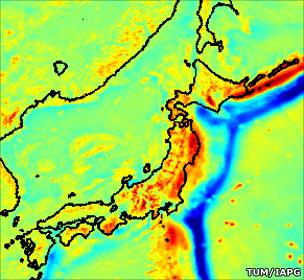

Those interested in earthquakes are also poring over the Goce results. The giant jolt that struck Japan this month and Chile last year occurred because huge masses of rock suddenly moved. Goce should reveal a three-dimensional view of what was going on inside the Earth.

"Even though these quakes resulted from big movements in the Earth, at the altitude of the satellite the signals are very small. But we should still see them in the data," said Dr Johannes Bouman from the German Geodetic Research Institute (DGFI).

To understand how ocean currents move you need to understand the role of gravity

Technically speaking, the model at the top of this page is what researchers refer to as a geoid.

It is not the easiest of concepts to grasp, but essentially it describes the "level" surface on an idealised world.

Look at the potato and its slopes. Put simply, the surface which traces the lumps and bumps defines the horizontal - it traces a surface on which, at any point, the pull of gravity would be perpendicular to it.

Described another way, if you were to place a ball anywhere on this potato, it would not roll because, from the ball's perspective, there is no "up" or "down" on the undulating surface.

It is the shape the oceans would adopt if there were no winds, no currents and no tides.

The differences have been magnified nearly 10,000 times to show up as they do in the new model.

Goce flies lower than any other scientific satellite

Even so, a boat off the coast of Europe (bright yellow) can sit 180m "higher" than a boat in the middle of the Indian Ocean (deep blue) and still be on the same level plane.

This is the trick gravity plays on Earth because the space rock on which we live is not a perfect sphere and its interior mass is not evenly distributed.

The Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer (Goce) was launched in March 2009.

It flies pole to pole at an altitude of just 254.9km - the lowest orbit of any research satellite in operation today.

The spacecraft carries three pairs of precision-built platinum blocks inside its gradiometer instrument that can sense fantastically small accelerations.

This extraordinary performance allows it to map the almost imperceptible differences in the pull exerted by the mass of the planet from one place to the next - from the great mountain ranges to the deepest ocean trenches. Just getting it to work has tested the best minds in Europe.

"Ten years ago, Goce was science fiction; it's been one of the biggest technological challenges we have mastered so far in the European Space Agency," said Dr Volker Liebig, the organisation's director of Earth observation.

"We measure one part in 10 trillion; that's beyond what we understand in our daily experience."

An initial two months of observations were fashioned into a geoid that was released in June last year. The latest version, released in Munich at a workshop for Goce scientists, includes an additional four months of data. A third version will follow in the autumn. Each release should bring an improvement in quality.

"The more data we add, the more we are able to suppress the noise in the solutions, and the errors scale down," said Dr Rune Floberghagen, the European Space Agency's Goce mission manager. "And of course the more precisely you know the geoid, the better the science you can do using the geoid.

"We are seeing completely new information in areas like the Himalayas, South-East Asia, the Andes mountain range, and in Antarctica particularly - the whole continent is desperate for better gravity field information, which we are now providing."

Goce sees gravity differences at Japan and the tectonic boundary (blue) that triggered the quake

One major goal of the Goce endeavour is to try to devise a universal reference to compare heights anywhere on the globe.

Professor Reiner Rummel, the chairman of the Goce scientific consortium, explained: "Usually, heights in the UK, say, are connected to one benchmark which is connected to mean sea-level, which might be measured at Liverpool, for example. The French do the same, the Australians do the same and the Chinese do the same - but mean sea-level differs from one country to the next. Now, with Goce, we can unify this so that we don't get the sort of surprises we had when they built the Channel Tunnel and discovered a half-metre offset between the UK and France."

The mission has funding up until the end of 2012 when, like all European Space Agency Earth observation missions, it must seek further financial support from member states to continue.

Goce has delivered the data promised in its primary mission - some 14 months of observations in total - but researchers would like to see it fly for as long as is possible.

Because it operates so low in the sky - a requirement of being able to sense gravity signals which are incredibly weak - it needs an engine to push it forwards through the wisps of atmosphere still present at its altitude.

Without this engine, Goce would rapidly fall to Earth. But the mission team reported here in Munich that Goce probably has sufficient propellant onboard to drive its engine until deep into 2014.

- Published18 February 2011

- Published21 December 2010

- Published17 December 2010

- Published17 January 2011

- Published7 September 2010